The 6 Most Progressive Ballot Initiatives Of 2018

Voters across the country are about to decide whether to adopt a number of ambitious policies in perhaps the biggest test of progressive ideas before the American public this November.

Three states are considering Medicaid expansion. Four are considering marijuana legalization. Voting rights expansions, anti-gerrymandering measures and restrictions on campaign spending are on the ballot in 12 states.

Others are experimenting with industry-specific measures. California could limit the profits of dialysis companies. Nevada and Arizona may require utilities to obtain 50 percent of their energy from renewable sources. Colorado could limit sky-high interest rates and hidden fees by payday lenders. Nebraska is considering whether to remove sales taxes from feminine hygiene products.

But some ballot initiatives go even further, establishing models and tactics that have the potential to be taken up by campaigners in other states. Here are a few of the most ambitious efforts state efforts.

1. Washington State is deciding on the country’s first carbon tax. Again.

From Oregon’s passing the first automatic voter registration law in 2015 to California’s committing to 100 percent renewable energy by 2045, the West Coast is becoming the country’s laboratory for progressive ideas. This year perhaps the boldest experiment is taking place in Washington state.

If it passes, Initiative 1631 will impose a fee of $15 per ton of carbon emitted by the state’s largest polluters. The revenue, an estimated $1 billion per year, would be spent establishing clean-energy projects and helping low-income communities affected by climate change.

This is the second time Washington has considered a carbon tax. The first, in 2016, proposed a revenue-neutral plan that would have collected more from polluters and directed the funds toward reducing other taxes. That measure lost decisively (59 percent to 41 percent), a result partly attributed to its opposition by labor groups and communities of color, which argued that revenue should be dedicated to building a green economy and assisting communities affected by climate change.

That’s the goal of the new version. Of the estimated $1 billion the carbon tax would bring in, 70 percent would go to renewable energy projects, 25 percent would be used to prevent and clean up pollution, and 5 percent would support low-income communities affected by climate change.

The new version is also a test case for an emerging strategy for progressive ballot initiatives. Rather than aim for the broad middle of the electorate, Initiative 1631 unabashedly aims blue. Rather than targeting messages and organizing at wavering conservatives, campaigners have been building a left-as-left-gets coalition that includes low-income advocates, unions, tribal leaders, communities of color and grassroots nongovernmental organizations.

“When conservatives talk about ‘tax and spend liberalism,’ when they talk about ‘Big Government liberalism,’” wrote David Roberts at Vox, “this is what they’re talking about.”

2. Washington voters might end impunity for police shootings

Despite all the attention drawn to the issue of police shootings in the past three years, only one state, Washington, will consider a bill to improve police accountability this November.

Initiative 940 aims to change the legal criterion for prosecuting police officers who kill civilians. Under Washington’s current law, prosecutors must establish that an officer acted with “evil intent” — a standard almost impossible to prove.

“You cannot hold officers accountable here, no matter how bad their behavior,” said Andrè Taylor, a co-chair of De-Escalate Washington, a group backing the initiative. When his brother Che Taylor was killed by police in Seattle in 2016, Andrè Taylor moved home to Washington from L.A. to start a nonprofit, Not This Time, and begin to unravel the structural factors that contributed to his brother’s death.

Washington, he found, has some of the worst laws on police accountability in the country and one of its lowest prosecution rates. Initiative 940 would lower the bar for police accountability, allowing prosecution of officers who employ deadly force without a reasonable expectation that their lives are in danger. This would align Washington with other states’ accountability frameworks. The initiative, notably, would require an independent investigation whenever a police officer kills or seriously harms a civilian and mandate de-escalation and mental health crisis training for all officers.

Its passage seems likely. Polls have consistently shown likely voter approval near 70 percent, and years of grassroots organizing have built a broad coalition of support that includes Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan, Democratic Sen. Patty Murray and even some law enforcement bodies.

“Everyone wants this,” Taylor said. “From Day One, we rejected the notion that citizens want impunity for officers who have power over them.”

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

3. Florida could enfranchise 1.5 million voters

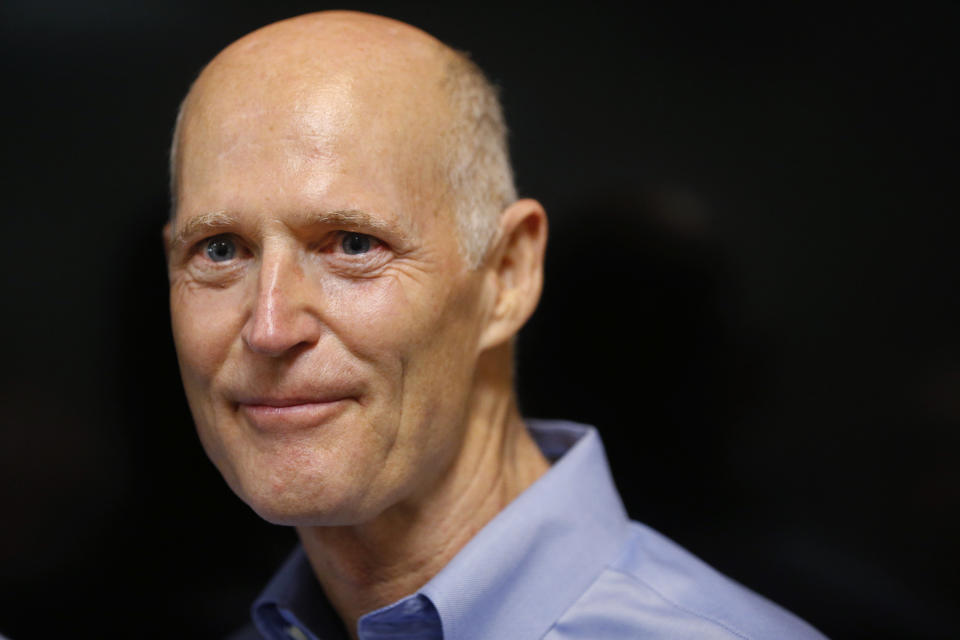

According to the Brennan Center for Justice, Florida has “one of the most punitive disenfranchisement policies in the country.” Felons are barred from voting for the remainder of their lives — a policy that affects roughly 10 percent of the state’s population. To regain this right, felons have file individual petitions for clemency, a process that Gov. Rick Scott summed up as, “We can do whatever we want.”

If Florida voters approve Amendment 4, it would restore these rights and could increase the state’s voter rolls by more than 1.5 million people. So far, it seems likely to pass. Every newspaper that has issued an endorsement backs the measure. Opposition to the amendment, organized under the name Floridians for a Sensible Voting Rights Policy, appears to consist of a single Tampa lawyer and has not run any ads or carried out any major campaign activities. Even the famously conservative Charles and David Koch have decided not to oppose it. The amendment needs at least at least 60 percent of the vote to pass, and polls released so far have found support over 70 percent.

If it wins, the measure has significant implications for the rest of the country. Though only three states permanently deny voting rights to felons, 34 impose some form of restriction on voting after a criminal conviction. Only two states allow incarcerated offenders to vote. A victory for Amendment 4 in Florida would give progressive campaigners across the country a good argument to reverse other forms of disenfranchisement.

4. Louisiana could reverse a Reconstruction-era tough-on-crime law

In a red state and a polarized election, Louisiana is running one of the few criminal justice reforms with bipartisan support.

The reform itself is simple. Only two states, Louisiana and Oregon, allow juries to convict defendants without a unanimous vote. Louisiana, though, is alone in allowing 10 jurors to overrule the last two in murder cases. The state’s Amendment 2 would align the state with 48 others in requiring unanimous juries for all felonies.

The origins of Louisiana’s jury rule are explicitly racist, the result of a Reconstruction-era effort to empower white jurors and swamp black ones. In 1898, at the constitutional convention where the rule was devised, lawmakers declared their intention to “perpetuate the supremacy of the Anglo-Saxon race in Louisiana.”

The jury provision appears to have worked as designed. An investigation published by The Advocate, Louisiana’s largest daily newspaper, found that black defendants were 30 percent more likely than white defendants to be convicted by split juries. Forty percent of convictions were carried out with at least one juror still expressing reasonable doubt. It’s not the only contributor to Louisiana’s sky-high incarceration rate, the second highest In the country, but it’s a significant one.

While no polls have been done on the referendum, its rare consensus among lawmakers and institutional actors is itself a sign of progress. The initiative sailed through the Louisiana House and Senate with significantly more than the two-thirds majority it needed to get on the ballot. Since then, it has attracted a swath of high-profile supporters, including the American Civil Liberties Union, the Koch-backed Americans for Prosperity, the “religious liberty”–promoting Louisiana Family Forum and the R&B singer John Legend.

5. Maine might establish universal home care for the elderly

With a median age of 44.5 years old, Maine has the oldest population in the country. But this November, its voters will have the opportunity to establish America’s first universal home health care system for seniors. Question 1 would establish a 3.8 percent tax on all income above $128,400 per year — above which wages are not taxed for Social Security. The estimated $300 million in annual revenue would pay for long-term, home-based health care services for all residents over 65 or with disabilities.

It’s an ambitious proposal and, politically speaking, an unpopular one. All four gubernatorial candidates oppose the measure, claiming it would chase away businesses and result in worker shortages. The state Chamber of Commerce, hospitals and health care companies have rallied to defeat it, calling their coalition Stop the Scam and issuing claims that, because the measure provides health care regardless of wealth, part-time Maine resident Martha Stewart could receive medical services before seniors living on fixed incomes.

No polls have been conducted on the measure so far. A similar state initiative, a tax on high earners to fund education, passed by just over 1 percent in 2016. It was repealed, however, when Gov. Paul LePage refused to enact it and the legislature passed a compromise bill that raised roughly half the revenue of the original proposal.

Regardless of the outcome, the initiative establishes a model for other states to take up and provides another example of the increasing ambitions of state-level universal health care efforts.

6. Ohio could overhaul how it treats drug offenders

One of America’s most ambitious and most controversial criminal justice reforms is on the ballot in Ohio. If successful, Issue 1 would turn felony drug possession charges into misdemeanors, loosen sentencing guidelines and prohibit jail time for probation offenses. It would also mandate that the state take all the money it saves by reducing its prison population and spend it on mental health and rehabilitation services.

The ballot measure is a case study in going big. The proposed legal changes are significant, updating laws relating to arrest, sentencing, probation and public spending. Issue 1 would apply the updated laws retroactively, allowing thousands of incarcerated Ohioans to petition for reduced sentences. Each of these components could have been its own initiative or quiet, behind-the-scenes tweak, but according to Stephen JohnsonGrove, the deputy director of the Ohio Justice and Policy Center and a co-author of the initiative, campaigners decided to go for the entire package at once.

“The core of this thing is one single idea,” he said. “It’s trying to shrink the prison population. If that’s your goal, you can’t do it in half-steps.”

Since the start of the campaign, though, things have gotten more complicated than he expected. The campaign spent months, JohnsonGrove said, choosing components and messages designed to appeal across the ideological spectrum. Campaign ads tout taxpayer savings and public safety. Nearly every message in support of the initiative emphasizes that it will not threaten the existing tough-on-crime regime for drug dealers and traffickers.

Despite this attempt at bipartisanship, though, Issue 1 has become hotly contested and furiously partisan. Both major-party gubernatorial candidates have been defined by their position on the initiative. Its financial backers such as George Soros’ Open Society Policy Center and Mark Zuckerberg have been attacked as out-of-state meddlers. Nearly every arm of the legal system, from county sheriffs to the chief justice of Ohio, has come out against it, arguing that it would hamper their fight against the opioid epidemic and make it harder to prosecute drug dealers.

And so, JohnsonGrove said, a ballot measure scrupulously written to avoid partisanship has become just another example of it. While no polls have been done on Issue 1 so far, the chance to capture the average voter may have passed. “If I had to give advice to other progressive campaigners,” he said, “I’d tell them to hope they get lucky.”

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.