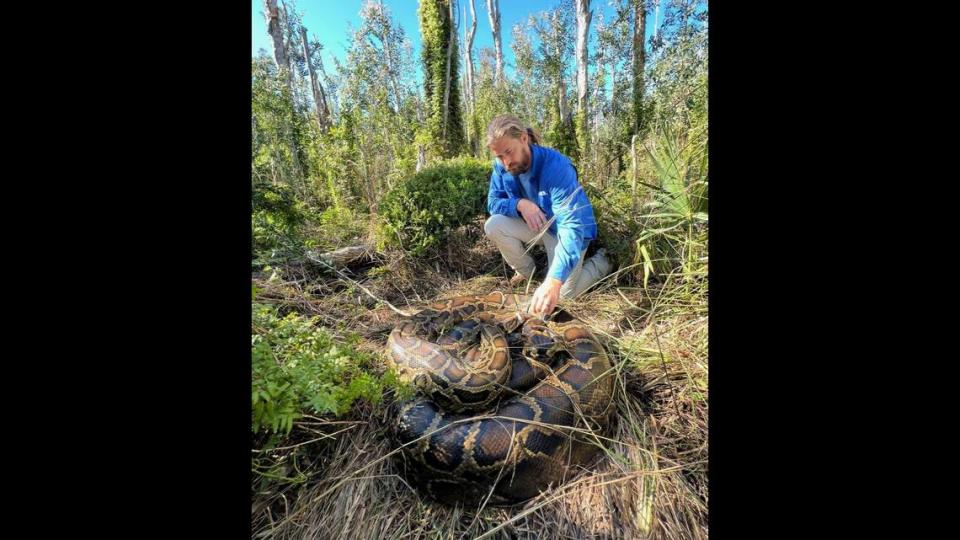

500 pounds of python caught when mating rituals revealed in Florida marsh, team says

The swamps of southern Florida are home to all manner of intimidating apex predators, but it was a new experience when a team of trackers found a 7-foot-wide mound of pythons in a marsh near Naples.

It happened Feb. 21 on public land in Collier County, and far more startling is the fact two mating balls were discovered in one day.

In all, 11 pythons were caught — one more than 16 feet long — bringing the tally to 500 pounds of snake.

That marked a record catch for the Conservancy of Southwest Florida’s decade-long battle to remove the invasive snakes, and proof their once-experimental radio-telemetry program is succeeding.

Both mating balls were found when conservancy staff put implants in male “scout snakes,” set them free, and followed the signals to remote areas where people seldom tread.

“It’s probably most people’s worst nightmare, but for us, it’s a good day. It’s a win for native wildlife,” the conservancy’s science coordinator Ian Bartoszek told McClatchy News in a phone interview.

““It was a moment to savor, not so much as a victory but as a really interesting observation on snake behavior most people will never get to see. There were so many large snakes together in the same place. Most would say it’s creepy, but it was creepy cool to see.”

Bartoszek says this despite having a python tooth stuck in his hand from a recent bite.

Tracking pythons

Since 2013, the conservancy has put trackers in 110 pythons and followed their movements across southwest Florida.

Much has been discovered about python behavior, including the size of their territories, the habitats they choose and the ability for the animals to group up together during the breeding season.

It became clear the implanted males could be weaponized to track down the females, and that led to a shift in the program’s goals.

Through early 2024, the conservancy has removed more than 1,300 pythons from a 150-square-mile area near Naples, most of them caught through the tracking program. That’s the equivalent of 35,000 pounds of snake, or more than 17 tons, Bartoszek says.

“The majority (of the females) were (pregnant) adults and some were off season captures that would have been reproductive the following year,” he says.

“The average clutch size of a female python in southwest Florida is 46 eggs. We have seen between 12-122 developing eggs (in captured females). We don’t have an updated figure but we are in the tens of thousands of eggs we kept from hatching by targeting adult females for removal.”

The breeding season window for capturing pythons runs from November to April, and calls for Bartoszek and his team to go where there are no roads. Once a signal is located, the trackers hike, kayak and wade through miles of wetland until the snake is found.

Wrestling is then required, including one-on-one brawls in canals and tug-of-wars at the entrance of burrows.

Day of mating balls

It was a pair of python bachelors named Hisstopher and George that led Bartoszek and the team to the mating balls on Feb. 21.

George was never seen that day, as he remained hidden underground, but his tracker led the team to the first mating ball, which included two males of around 45 pounds each and a 16-foot, 125-pound female, he says.

“The big one was so long and heavy we had to drape her over multiple shoulders and march her out. We didn’t have a snake bag big enough to hold her,” Bartoszek says.

“She had to be shoved (still alive) in the front of the kayak, to be paddled back to our field truck.”

A far-bigger pile of snakes was found an hour later, when Bartoszek, biologist Ian Easterling and two assistants tracked down Hisstopher, he says.

The writhing mound was a stunning 7 feet wide, with heads and tails in every direction. The snakes appeared in no hurry to escape, which allowed the team to closely study the ball.

It contained five males in the 30-pound range, and a 14-foot, 85-pound female. Two additional males were found lounging not far away.

Among the details the team found interesting was where the snakes had chosen to mate.

“The snakes were huddled together in a sunny patch of forest surrounded by ferns,” Bartoszek said. “This elevated feature was basically an island in the surrounding wetlands and we had not captured any snakes from this sector of the forest before.”

All were captured, bagged and marched alive out of the swamp. Except for Hisstopher, that is. He was set free to lead another female to her doom.

“For 10 years, we’ve been catching and putting them down humanely. You can’t put them in zoos and send them back to Southeast Asia,” Bartoszek says.

“Invasive species management doesn’t end with rainbows and kittens. These are remarkable creatures, here through no fault of their own. They are impressive animals, good at what they do.”

Is science winning?

Burmese pythons are native to Southeast Asia and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission suspects they made their way into the wilds of Florida as exotic pets that escaped or were intentionally released.

Necropsies have revealed they are eating at least 24 species of mammal, 47 species of bird and three reptile species in South Florida, according to University of Florida research.

In one case, a 31.5-pound python ate a 35-pound deer. “We see the remains of deer inside pythons often. This is concerning and it should sound an alarm.” Bartoszek says.

Even more frightening is the fact they may be expanding their turf to the north and showing up in seemingly impossible places. In 2017, a python was found in open water nearly 15 miles off the coast of southwest Florida, Bartoszek wrote in a scientific note published in Herpetological Review.

The conservancy — one of Florida’s largest environmental organizations — was among the first to take action, launching a ground war that has lasted more than a decade.

Catching 11 snakes in a day shows the tracking program is working, but not in the way people might think, Bartoszek says.

That’s definitely a lot of snakes to catch in a day, but the more important detail is that nearly a dozen males were found and with so few mating options, they were all after the same two females. (Two additional telemetry programs are now operating in the eastern part of South Florida, one led by the University of Florida and the other from the U.S. Geological Survey.)

“It’s a big Everglades. I’m not declaring victory by any stretch, but we are winning key battles. We feel like we are attempting to hold the line around Naples while we all wait for additional control tools to develop,” Bartoszek says.

“There’s an area where we had four active scouts and they have not found us a female in that sector this season. ... We are cautiously optimistic, you can’t take (1,300) snakes out of the equation and not make an impact.”

‘Swamp justice’? Cyclist crosses paths with gator eating python in Florida Everglades

200-pound python proves Florida wilderness is an all-you-can-eat buffet, experts say

215-pound invasive Burmese python is heaviest to be found in Florida, biologists say