50 years ago, U.S. Supreme Court heard case to integrate metro Detroit schools

The issue of cross-district busing profoundly polarized metro Detroiters in the early 1970s after courts ruled students should be transported between the city and 53 suburban districts to equalize access to education for Black students. At the time, Detroit schools were about 70% Black and suburban schools were more than 90% white. Fifty years ago, lawyers squared off before the U.S. Supreme Court in the landmark case known as Milliken v. Bradley. Spoiler alert: In July 1974, the court ruled against cross-district busing in a 5-4 decision.

The following article appeared in the Free Press on Feb. 28, 1974.

WASHINGTON ― The U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments in the Detroit school integration case Wednesday, but there were none of the spirited exchanges between members of the court and attorneys that have marked hearings in similar cases.

The case, which the NAACP has said may be the most important since the Supreme Court's 1954 school integration decision, raises the question of whether or not a busing order for a mostly Black city school system like Detroit's should include white students living in the suburbs or must stop at the city line.

The routine hearing Wednesday captured none of the drama of that issue, however. Many of the questions by the justices indicated they are not as familiar with the details of the Detroit case as they were with a similar metropolitan school integration case a year ago from Richmond, Va. They will not likely issue a decision before June, based largely on written briefs already filed by the conflicting parties in the suit.

Attorney General Frank Kelley opposes the NAACP

Justice Lewis F. Powell, whose decision not to participate in the Richmond case helped produce the 4-4 deadlock that left the issue of metropolitan school integration unsettled, asked only a few minor, technical questions Wednesday.

The court's two other swing justices, Potter Stewart and Byron R. White, also asked questions that gave little insight into their feelings on the Detroit case.

The NAACP, which brought the suit, has contended successfully in lower courts that the state is guilty of deliberate segregation of Detroit area schools.

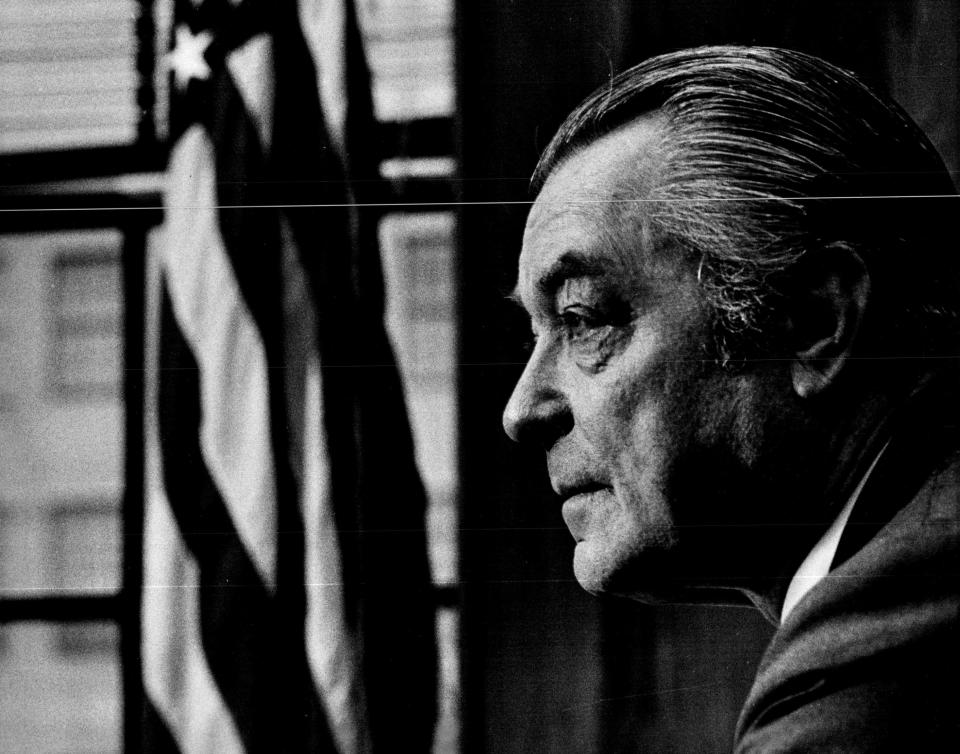

Michigan Attorney General Frank J. Kelley has argued that the state is not guilty, and several suburban attorneys have contended that even if the state is guilty, suburban school districts can't be involved in any busing plan unless they are individually found to have acted in discriminatory fashion.

Suburbs say only Detroit has discriminated

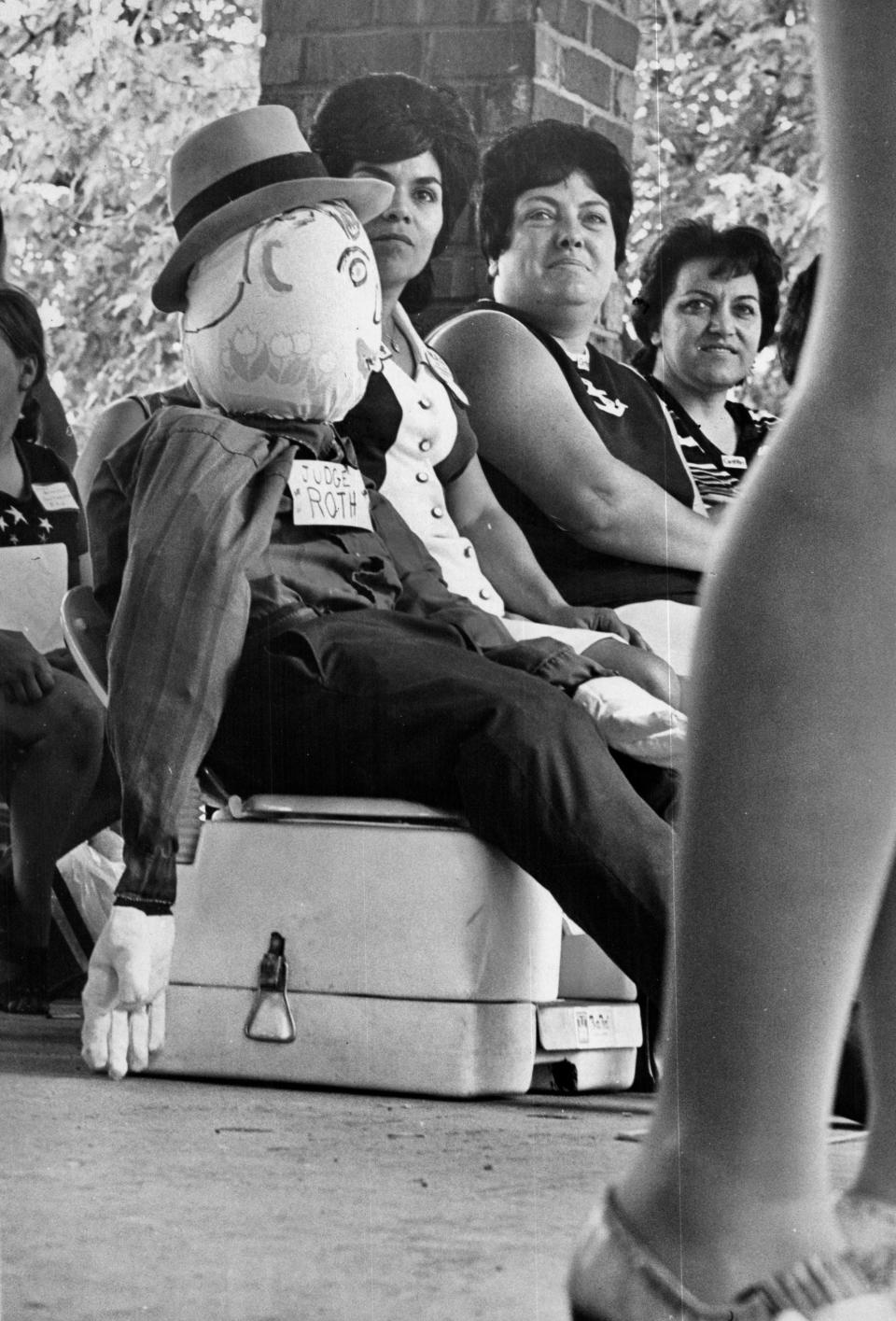

The U.S. Justice Department has supported that view. The Supreme Court has before it only the principle of metropolitan school integration, not any specific plan since the U.S. Sixth Circuit of Appeals told U.S. District Judge Stephen J. Roth to hold mere hearings before ordering a plan. The Supreme Court members nevertheless seemed interested Wednesday in just how such a plan might work.

Justice William J. Brennan asked: "What happens if a school system finds itself with more students than it has budgeted for?" And Justice White asked if suburban Detroit taxpayers can "fairly be taxed to pay the expenses of the desegregation of Detroit?"

More: Before joining high court, Thurgood Marshall made history in Detroit

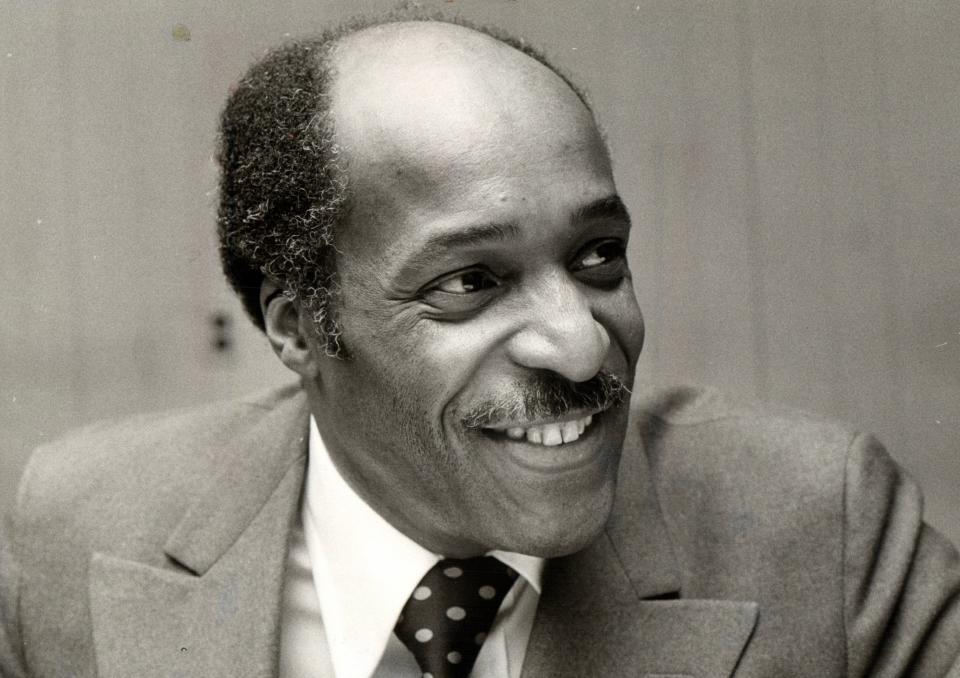

Nathaniel R. Jones, general counsel of the NAACP, responded to both questions by saying those were issues Judge Roth would have to consider in ordering any particular integration plan. Jones and J. Harold Flannery, who also argued for the NAACP, said repeatedly that there is no integration order and the court faces only the question of whether a school integration order must stop at the Detroit city limits.

The suburban districts' attorney, William Saxton, argued that school integration should stop at the city line.

"Absolutely no school district in the state, with the exception of Detroit," Saxton said, "has committed any act of segregation."

Saxton said there should be a Detroit school integration plan. But, he added, suburbs should not be included because the "mere existence" of white schools in the suburbs "does not offend the Constitution."

Harvard students camp out all night

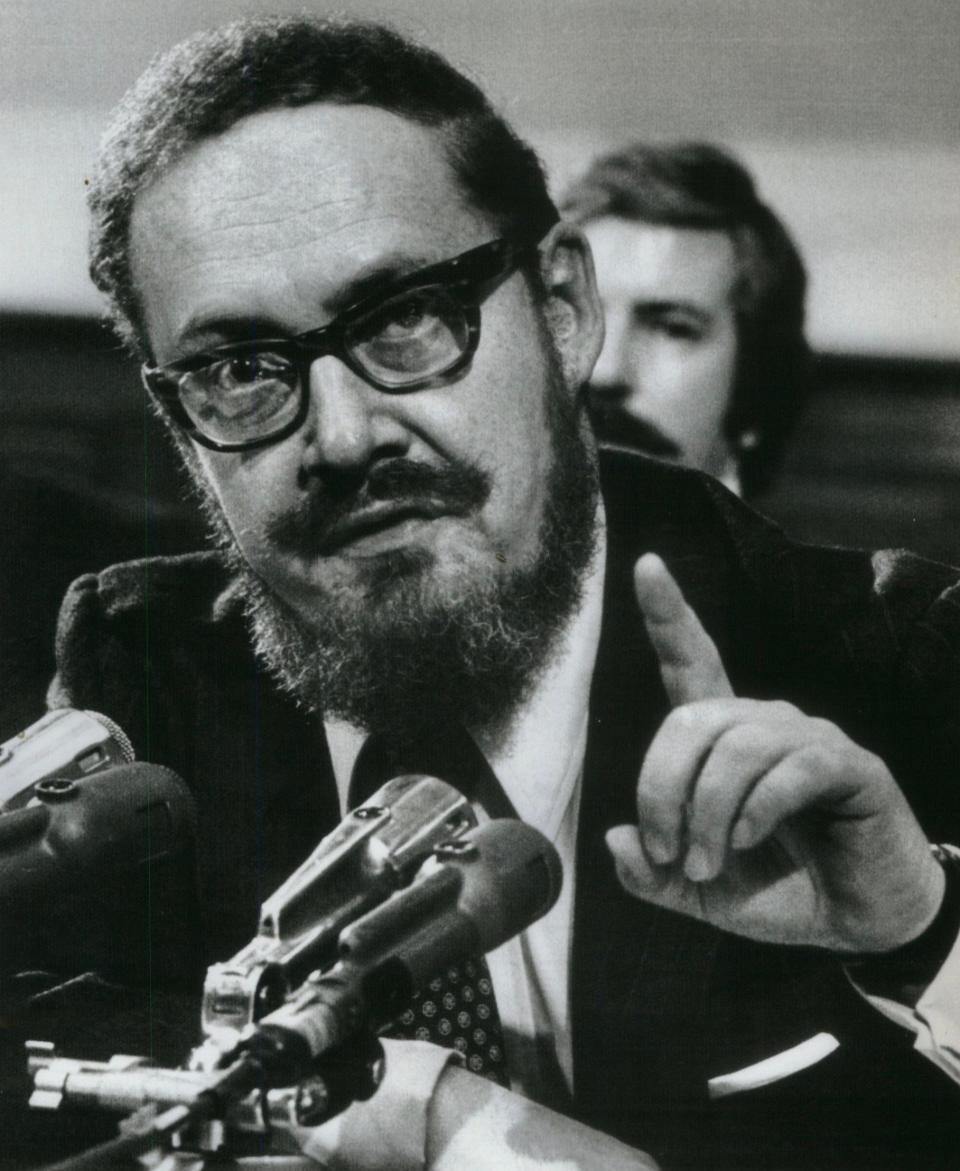

A similar position was taken by U.S. Solicitor General Robert Bork, who argued that a school integration plan limited to Detroit would be the proper solution for the segregation Judge Roth found. A metropolitan plan "is so disproportionate to the violation that it is an impermissible exercise of judicial power," Bork said.

Bork urged that the case be sent back to Roth, where the NAACP could be permitted to demonstrate, if it can, that suburban schools are illegally segregated.

Flannery said the NAACP viewed that as a "middle ground" the Supreme Court could take. But Saxton and Attorney General Kelley, who argued for the state, told the court they want the metropolitan idea rejected out-of-hand without a remand of the case to Judge Roth.

Kelley and Saxton won a small victory Wednesday when they successfully blocked the NAACP's use of a giant map showing schools in Detroit to be mostly black and those in the suburbs to be mostly white. NAACP attorneys presented each justice with a small version of the map instead, and Saxton also objected to that.

Justice Stewart indicated the court was not likely to use the map in its discussion of the case. NAACP Executive Director Roy Wilkins was present for the arguments, as were a variety of Detroit and Michigan officials. The room was filled with so many attorneys and other spectators linked with the case that only a few seats were available to the general public.

One spectator with deep interest in the case was Mary Ellen Riordan, president of the Detroit Federation of Teachers. Some seats went to a group of Harvard law students who camped on the steps of the court building all night.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: 50 years ago this week, US Supreme Court heard Michigan schools case