50 died when cargo ship sunk off coast of SLO County more than 100 years ago. What happened?

Speculation surrounding mystery bales of cotton and empty whiskey barrels washing up on the North Coast are an echo of the wild conspiracy theories surrounding the S.S. Roanoke, the almost forgotten maritime tragedy that was likely the most deadly in San Luis Obispo County history.

The 1916 voyage was supposed to be just beginning when it ended with fatal results for almost everyone aboard.

The S.S. Roanoke departed San Francisco bound for Valparaiso, Chile, with a cargo of dynamite, wheat, oil and kerosene.

Captain Dickson was so confident of a smooth trip he even invited his wife.

But the seas were rough off the coast of California.

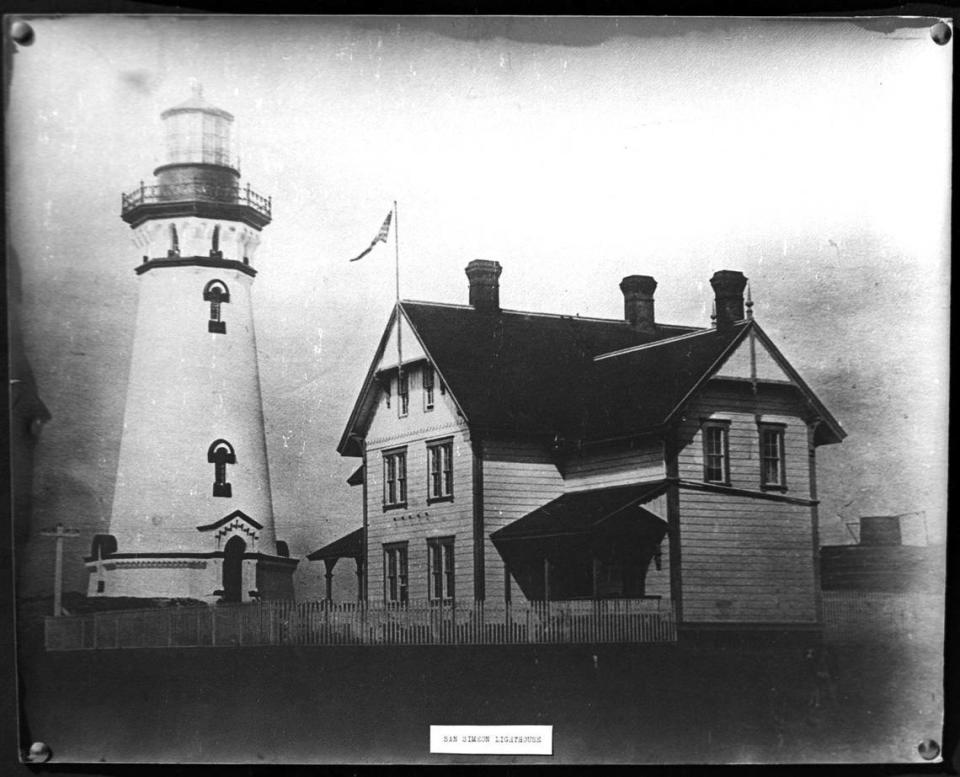

The Roanoke sank 50 miles north of San Luis Obispo, about 3 p.m. on Tuesday, May 9, 1916, about 15 miles out to sea, west of the Piedras Blancas Lighthouse.

According to the Daily Telegram of May 12, 1916, there were 53 souls aboard, 48 crew members and three “Mexican stowaways” in addition to Dickson and his wife.

Only three would survive: Manuel Lopez, Joseph Elb (alternatively spelled Erb in a few stories) and Charlie Rabeiro. They were recovered in a lifeboat near the lighthouse with five other men who had died of exposure after over a day on the water.

At least three ships passed in sight of the stricken Roanoke but didn’t know the ship was in distress.

Lopez later testified at a federal hearing that the radio’s dynamo that powered the unit was not in workable condition.

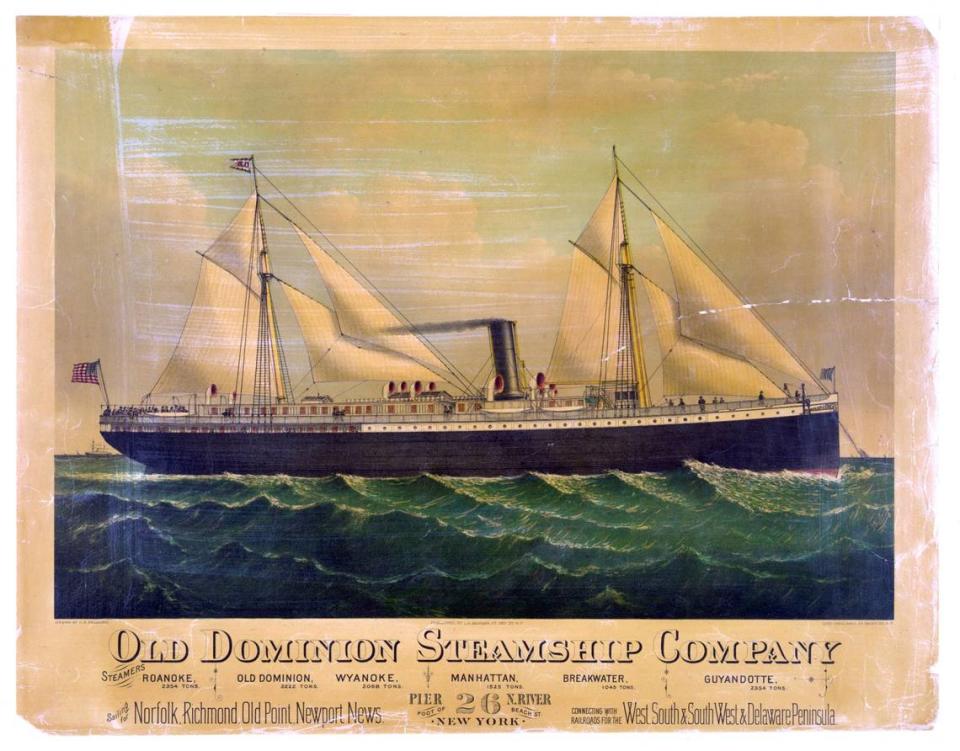

Ill-fated ship carried first Mormon immigrants, gold miners

The S.S. Roanoke was built in 1882 for the Old Dominion Steamship Company serving the Atlantic seaboard.

Notable early passengers were some of the first Mormon immigrants.

The Alaska Gold Rush saw the steamship sold to a Pacific coast company where it made the run from Seattle to St. Michael, Alaska. There passengers would transfer to river steamers up the Yukon River. Later, it offered service to Nome, Alaska — the location of a later gold strike.

When Klondike business faded, the ship was sold again and worked primarily along Oregon and California routes.

On its last voyage, the ship was about 34 years old and was filled with cargo rather than passengers.

Conspiracy theories abound in wake of ship sinking

The disaster brought on conspiracy theories, a phenomenon not unique to our time — largely speculation that completely ignored eyewitnesses survivor statements.

North Pacific Steamship Co. lawyer E.E. Sooy theorized to a Daily Telegram reporter that a “silent bomb” had sunk the ship.

“The fact that none of the three survivors remember hearing any explosion does not mean that there was not one,” Sooy said.

The same May 12, 1916, story said the president of the steamship company had personally overseen the ship’s loading.

Survivor, Joseph Elb said the ship was listing to the port side after the cargo shifted before leaving the harbor. One report attributed the shifting to a hard turn.

The wildest theory ran under a headline, “Did the Roanoke sink or steam for Europe? Weird theory is out” on May 15, 1916.

In that, a Santa Barbara bank manager speculated the ship had sailed for Europe, via the Panama Canal, sending the explosives to the region inflamed by almost two years of the first world war.

Dickson formerly worked at Port San Luis, according to a May 11, 1916, Daily Telegram story. He had captained the Union Oil tanker Argyle until recently. Many years earlier, he had been in charge of the tug boat “Liberty” at the port “and is kindly remembered by parties familiar with port life then,” the article read.

“The fate of Capt. Dickson and his wife, who was the only passenger aboard, remains a mystery,” the Daily Telegram said. “Joe Elb, one survivor, says the last he saw of him, he was standing on the bridge of the boat. Another report says Dickson sent his wife into a boat but refused to leave the boat (Roanoke). When the lifeboat containing his wife capsized, he sprang overboard to rescue her and both perished together.”

Survivors tell of harrowing sinking off SLO County coast

Two of the survivors shared their stories which were certainly more believable than the conspiracy theories.

They were interviewed after a hospital stay in the May 11, 1916, Daily Telegram and days later would have similar testimony at a federal probe into the accident.

Here is what they said — with the many typos cleaned up.

Joseph Elb, quartermaster

“I attribute my escape to the fact that I had hold of an oar practically all of the 27 hours we were out in the life boat,” Elb said. “While I was not clad any warmer than the others, constant exercise at one of the oars kept me in better condition. Only one of the five who perished took active part at the oars and he was the last to give up.”

“We didn’t feel much like eating on the boat, only a little hardtack,” Elb continued. “A can of biscuits was unopened. There was plenty of drinking water but only a few sups were taken as all were so cold.”

He concluded: “The Steamer sank about 3 p.m. Tuesday afternoon, and when night came on, we cast our anchor so we wouldn’t drift onto the coast. When it got light yesterday morning, two in the boat were dead. Three others died during the day — the last one, I think, just at the breakwater. I remember seeing the lighthouse vaguely, but didn’t know anything more.”

Manuel Lopez, oiler

“Crew of the Roanoke was inexperienced,” Lopez said. “Crew was picked up on the water front and few knew any of his mates. Very few knew a thing about launching a lifeboat. An experienced crew could have had a chance for life.”

“When the ship listed to starboard at three o’clock Tuesday afternoon, the six boats on the port side of the ship were cut loose with difficulty. The others were out of reach,” he said. “The vessel was badly loaded. I remonstrated with Capt. Dickson as to the manner in which the boat was loaded, also told him it was unwise for him to take his wife with him on such a voyage with such a cargo.”

According to Lopez, the main cargo of the Roanoke was dynamite, though the “top deck was heavily loaded with wheat and oil, including kerosene.”

“Shifting of cargo in the heavy sea was the sole cause of the disaster,” he said.

Lopez said two of the lifeboats “were swamped as they were launched.” He said one of the missing boats after the sinking had “the second mate as the only occupant. The other has eight men.”

He concluded: “The vessel listed for hours and had we been able to use our wireless we could have secured help. We sighted three vessels while the vessel was still afloat, but could not attract them.”