The 40 Greatest Stand-Alone TV Episodes of All Time

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Whether we’re living in the age of Peak TV or Trough TV, one thing is clear: There’s too much TV. Thankfully, not every show has to be watched in its entirety. One of the best things about television is its serialized nature, the continuous thread that strings viewers along from one episode to the next. It’s a cliché that prestige television is the new novel precisely because of the way that many dramas develop their characters and plots over many hours of storytelling. But an older virtue of TV is its brevity—the way a scenario can be introduced and resolved within the space of an hour, or half that—and some of the best episodes are less like chapters in a long-running novel than like short stories or short films. These are stand-alone episodes.

What makes a stand-alone? There’s been no shortage of debate about this question, but for our purposes, we’re defining it simply as an episode that stands up on its own, whether or not you’ve seen the rest of the show. Some are “bottle episodes,” which typically confine a small cast to one location to save money. Some are “departure episodes,” in which a show abandons its usual format or style to suddenly become, say, silent, animated, a musical, or about a minor character it was never about before. But not all bottle episodes and departure episodes are stand-alones, and vice versa. It’s for this reason that you won’t find Breaking Bad’s celebrated “Fly” on this list: It may be a bottle episode, but it doesn’t stand alone, because the best thing about it—how the housefly is a metaphor for everything else going on in the series—is comprehensible only to those who have watched the show.

In this list, we present our picks for the 40 greatest stand-alone episodes of all time, from monster-of-the-week episodes to installments of anthology series and old-fashioned sitcoms to daring formal experiments to, yes, bottle episodes. These are English-language selections, and, out of fairness, we have limited ourselves to one episode per series, although some shows are full of stellar contenders. Use these picks—arranged in chronological order, with an admitted bias toward our most recent, and best, era of television—to populate your streaming queue with a feast of bite-sized morsels, each of which could double as either a snackable introduction to a new show or a satisfying meal in itself.

If movies made Alfred Hitchcock a name, TV made him a brand. The master of suspense embraced the burgeoning medium in 1955 with Alfred Hitchcock Presents (later renamed The Alfred Hitchcock Hour), an anthology series whose entries began and ended the same way: the titular celebrity providing context to a unique half-hour thriller, typically an adaption of a short story by an esteemed author (John Cheever, Ray Bradbury, many others). Though he’s omnipresent throughout this long-running series—361 episodes over 10 years—Hitchcock directed only a few Presents episodes, satisfying himself with hosting duties while cranking out cinematic wonders like Vertigo throughout the show’s run. Still, those self-helmed episodes are among the show’s best, early proof that the smaller screens and home comforts afforded by television could not stanch the chilling effects of a perfectly staged fear fest. “Breakdown,” the seventh episode, is an exemplar.

“Breakdown” stars Joseph Cotten—known to Hitchcock fans from Shadow of a Doubt—as William Callew, a coldhearted movie executive who ends up wholly paralyzed after a car accident, his immobile body jammed into the front of his convertible. We hear Callew’s wrenching internal monologue as he helplessly awaits rescue, only for passersby to either rob him or leave him for dead. It’s a simple, devastating setup: close-ups of Callew’s frozen, stunned face; a wrenching stream of his thoughts, emotionally narrated by Cotten; an unbearable dramatic irony, as we see and hear the surrounding events that Callew can only fear; the tense anticipation of his ultimate fate. It’s absorbing psychological horror of the kind only Hitchcock could pull off, and “Breakdown” may be the closest thing we have to a top-tier Hitchcock flick custom-fitted for TV. —Nitish Pahwa

Streaming on Peacock, Tubi, and the Roku Channel.

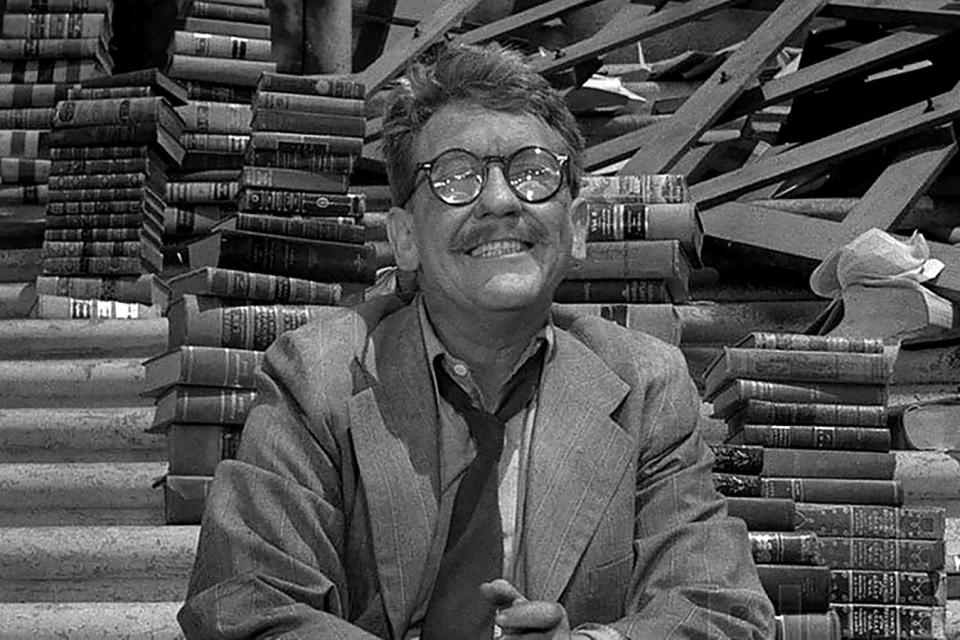

Ah, Mr. Henry Bemis, our misanthropic bibliophilic bank teller whose infamous “eight-hour tour of a graveyard” has haunted viewers for more than half a century. If the best of the original Twilight Zone series blended intensely dark humor with Cold War–era existential angst, Bemis’ particularly grim run-in with the warning “be careful what you wish for” in “Time Enough at Last” is that brew distilled to a sickening shot—with a plot twist worthy, as Bemis himself would surely agree, of the Book of Job.

As Rod Serling narrates in this stand-alone episode—the most exquisite that the classic anthology series has to offer—Henry Bemis, played by the singular Burgess Meredith, is “the small man in the glasses who wanted nothing but time”—time, specifically, to read. But his world, represented by a dummy boss and a contemptuous wife, is not one that values literature. Nor does it value its own survival, for that matter, as Bemis realizes once an H-bomb interrupts his lunch break in the bank vault, silencing all those nattering chastisements for good. At first, our sole survivor of the apocalypse isn’t quite sure that he wants to be alive. But then his sidelong glance at suicide is broken by something more attractive: a library! With unlimited borrowing privileges! I don’t want to spoil the final twist, but suffice to say, “Time Enough” is well worth a look if you haven’t seen it. The episode features themes—social alienation, just deserts, a cruel yet pithy universe—that show up throughout the series. And ultimately, Bemis’ tale offers a fantastically bleak object lesson of life in the Zone: It really, truly just isn’t fair. —Bryan Lowder

Streaming on Paramount+, Amazon Freevee, and Pluto TV.

The original Star Trek is full of stand-alone episodes, but one stands out as the best of them all. “The City on the Edge of Forever” is the platonic ideal of a science-fiction drama. After an accident alters history with devastating results, Captain Kirk and Spock go back in time to set things right. While in Great Depression–era New York, Kirk and Spock befriend an altruistic social worker named Edith Keeler, who, like the spacemen, is out of place in the 20th century. Edith dreams of a space-faring, utopian society without greed or war. Kirk quickly falls in love with her, and so does the audience. But in order to restore the timeline, Edith Keeler must die. Is saving the universe as Kirk knows it worth the price of sacrificing his lover?

With its expansive stakes and emotional depth, “The City on the Edge of Forever” feels more like a self-contained movie than a regular TV episode. It covers substantial terrain in 50 minutes, but doesn’t leave any loose threads hanging. That this is a time-travel episode makes it particularly sturdy as a stand-alone story: Because the characters are removed from their typical outer space setting, new viewers don’t have to be familiar with any starship technobabble or 23rd-century lore to follow along. And since the plot is driven by a love story set in 1930, it appeals even to people who aren’t big sci-fi fans. —Sol Werthan

Streaming on Paramount+ and Pluto TV.

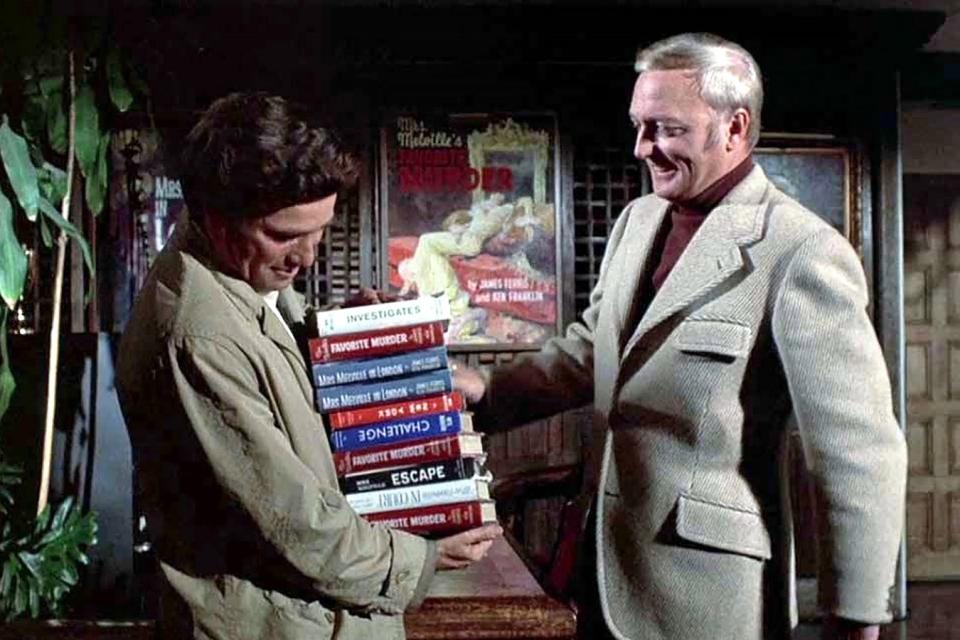

Every episode of Columbo is a stand-alone: Each one begins by showing the viewer a murder, including whodunit, and the mystery, then, is how Lt. Columbo will crack the case. (This “howcatchem” format is one of the many aspects of Columbo that writer-director Rian Johnson lifted for his similarly wonderful show Poker Face.) Unlike with many other procedural dramas, there’s no backstory, no multiple-episode arcs, no will-they-or-won’t-they plots. (Columbo is happily married to Mrs. Columbo and remains that way.) Peter Falk first donned the character’s rumpled raincoat for two made-for-TV movies—the pilots—and the format continued for 10 subsequent seasons.

But not every episode of Columbo is written by NYPD Blue creator Steven Bochco, and only one was directed by Steven Spielberg: “Murder by the Book,” the series’ first official episode. Spielberg was 24 years old, and you can tell from the wordless opening that he was determined to show the world how much he could convey with just the movement of his camera. “Murder by the Book” has all the cozy delights that would make Columbo a hit around the world and a cross-generational classic, from a deliciously hateable villain to the way Columbo unmasks the scoundrel with a casual “just one more thing …” In this case, that scoundrel is a murder mystery writer, and as in Johnson’s Knives Out, the victim is one too. The episode may not be as twist-packed and star-studded as that movie, but half a century later, it still holds up, and there probably wouldn’t be a Knives Out without it. —Forrest Wickman

Streaming on Peacock, Amazon Freevee, and Tubi.

The best British sitcoms make the most of their 30 minutes, wasting no opportunity for an underhanded jab or subtle visual gag. There’s no better example than Fawlty Towers, the beloved two-season BBC program created in the 1970s by Monty Python stalwart John Cleese (who now may be reviving it). The show, which spans a brief 12 episodes, spends little time on developing character or lore. What you see in each installment is what you get: a crumbling hotel owned and operated by the bumbling, arrogant Basil Fawlty (Cleese) and his stern, better-adjusted wife, Sybil (Prunella Scales), both of whom deal daily with clumsy assistants and booze-happy guests.

“The Germans” provides the Fawlty-curious a madcap showcase of the sitcom’s id. With Sybil in the hospital, Basil is left on his own to run a fire drill and host some guests of German origin at Fawlty Towers. Seems simple enough, except that Basil can’t hang up a decorative moose head or even follow his own orders—“Don’t mention the war!”—making everything worse in his attempts to demonstrate that he’s got this. Cleese is in brilliant form, running through fast-paced insults, tortured screaming bouts, constant trips and falls, and even short-term memory loss with perfect timing; little wonder this is Martin Scorsese’s favorite episode. (A note: “The Germans” has been the subject of modern-day controversy over a minor character’s racist rant. But as critics have noted, the episode clearly does not let its characters off the hook for their glaring foibles, that one especially.) —N.P.

Streaming on the Roku Channel.

Watching this 1975 episode of the original great workplace sitcom, you might focus at first on what feels so old-fashioned about it: the laugh track, the 50-year-old hairstyles, the opening credit sequence you’ve perhaps seen parodied more times than you’ve actually watched the show itself. Yet the longer you stick with this all-time classic episode, the more modern it seems. It’s not just the spiky yet affectionate relationships between its vivid characters—so archetypal, thanks to MTM’s influence, that you need no introduction to enjoy them. It’s not just that the episode’s centerpiece—Mary, who’s scolded her co-workers for being insufficiently solemn at the death of a local children’s-show clown, absolutely loses it laughing during Chuckles’ funeral—is still screamingly funny. It’s that the show insists on exploring the deeper questions behind its darkly comic premise, turning a simple sixth-season gag-fest into a moving (and still funny!) philosophical inquiry into why we laugh … even at the most inappropriate moments. —Dan Kois

Streaming on Prime Video and Hulu.

Poor, dim bartender Coach gets taken for eight grand by a con man, and only another con man can help: Harry “The Hat,” played by guest star (and future Night Court lead) Harry Anderson. Harry can help turn the tables on that rat—or maybe he’ll just hoodwink everyone in the bar. This plot-heavy episode depends not on any familiarity with these characters, but instead on pure suspense: Will the plan work, or will the gang get double-crossed? The poker con, which takes up the entire third act, is still one of the great set pieces in TV history. And you’ll gasp just like the studio audience did at the episode’s final twist. —D.K.

Streaming on Hulu and Paramount+.

What did they mean when they said Seinfeld was a show about nothing? They meant that, just as the show was getting popular in its second season, Larry David could make an entire episode about its characters not getting a table at a restaurant, and despite NBC’s befuddlement at the premise, the result would be a hothouse masterpiece. Jerry, Elaine, and George are so rich in neuroses, foibles, and anxieties—and the show so ruthless in aggravating them—that “The Chinese Restaurant,” a classic bottle episode, becomes a kind of theological experiment: three modern buffoons enduring escalating punishment from a malevolent god. We chose this one over Season 3’s similarly existentialist “The Parking Garage” because not everyone wants to watch Kramer. —D.K.

Streaming on Netflix.

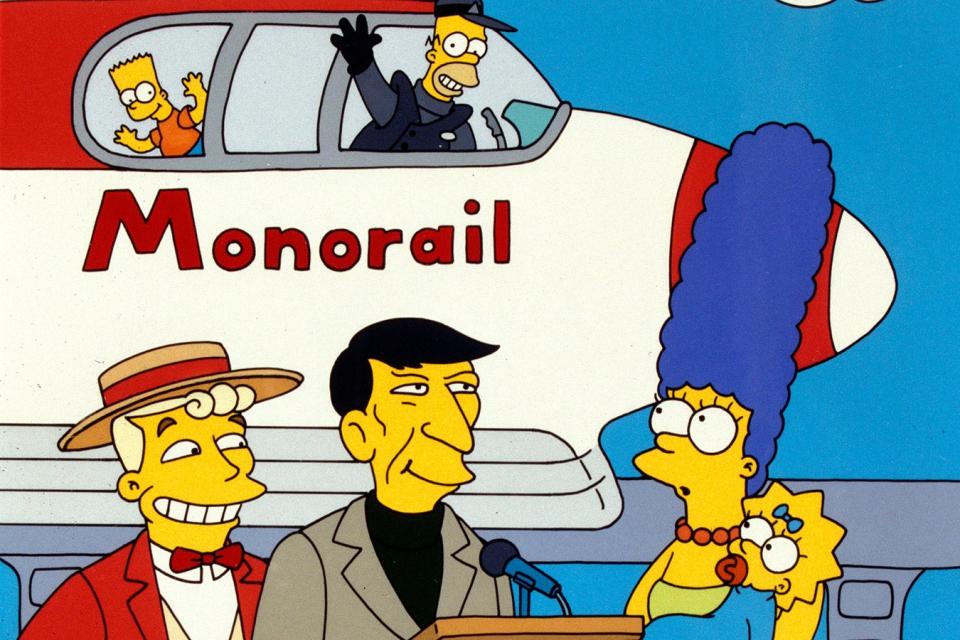

The Simpsons institutionalized a densely referential style of comedy in which pop cultural landmarks blaze by like blurry road signs, but you don’t have to know anything about Beverly Hills 90210 or the 1964 World’s Fair to love this 22-minute classic, written by a rising star named Conan O’Brien. The small town of Springfield’s main street is in desperate need of repairs, but a fast-pattering con artist sells the naïve townsfolk on a spiffy new monorail, brushing away the handful of objections with rhyming rejoinders, Harold Hill–style. (“Were you sent here by the devil?” “No, good sir, I’m on the level.”) It’s a tale so iconically American that the Simpsons themselves can barely sway its course, although in the end, it’s stupidity and not goodness that saves the day. —Sam Adams

Streaming on Disney+.

We’ve all known what it’s like to be the exploited underling—the person busting their ass nonstop, taking the rap for things that aren’t their fault, professing resilience in the face of chaos, only to remain underrecognized and ill-appreciated for all that effort. In that sense, The Larry Sanders Show’s “Arthur After Hours” is a universal story. Instead of exploring the broader machinations of the fictional late-night program hosted by Larry Sanders (the late, great Garry Shandling), this episode narrows in on that show’s tough-loving, wisecracking producer Arthur, played by Rip Torn. Background isn’t necessary to get what’s happening here: Artie capably makes his way through a deluge of absurd staff requests, a phone call from a greedy ex-wife, and other last-minute show disruptions—until Larry bumps Artie’s friend Ryan O’Neal (playing himself) from the schedule so that the always-horny host can keep flirting on screen with guest Sandra Bernhard (likewise playing herself), in a decision that Larry pins on Artie. Torn, always a memorable Larry Sanders player, is simply dazzling in his extended reaction to this betrayal, conveying all the degrees of Artie’s anguish with aplomb: rollicking drunkenness, tearful sadness, defiant rage, childlike impulsiveness, tender love for Larry. His roaring gusto and growling pain can be felt from across the screen, his whiskey-soaked cries professing a relatable, piercing vulnerability. And that’s all before a narrative twist reveals even more about the tough relationship between Larry and Arthur—but you’ll have to find that out for yourself. —N.P.

Streaming on Max.

“Home” isn’t an episode of The X-Files. It is a frightening, nasty little movie in which the camera taking the perspective of a crying infant being buried alive is only the beginning. The tale is spare: Young boys playing baseball in off-the-map Pennsylvania discover the murdered baby, and Mulder and Scully travel to investigate the death. They soon turn their attention to the Peacock brothers, who live on an isolated farm not far from the gravesite, and whose family has apparently been inbreeding since the Civil War. After an autopsy of the disfigured baby, Scully suspects that the brothers are holding a woman against her will at their home—but the truth is, uh, a lot more out there.

“Home” gestures at the classic X-Files schtick (it was 1996, and there is a “Baa-ram-ewe” joke), but the episode has a dead, menacing air and a notable detachment from the series’ famous protagonists, who seem just as horrified by the proceedings as everyone else. Four years before they gifted and cursed the world with the Final Destination franchise, longtime X-Files writers Glen Morgan and James Wong returned to the show they helped shape and created an episode so intense that it’s still banned from re-airing in many syndication deals. Watch it with the lights out on a weekend night, and take something strong to sleep afterward. —Jeffrey Bloomer

Streaming on Hulu and Amazon Freevee.

“You think I don’t want you to nail the guy who killed me?” howls Vincent D’Onofrio in this adrenaline hit of an episode, a one-hour, three-act drama about two difficult men facing the ultimate adversary. D’Onofrio plays an abrasive commuter who’s pinned between a subway car and the tracks; Andre Braugher is the chilly detective who’s investigating his murder—since, it’s clear, he’ll die the instant he’s pulled free. It’s a masterful portrait of rage and desperation, a gripping procedural, a Beckettian bleak comedy—and a showcase for its two leads, both among the most electrifying actors of their generation, who find the humanity in an inhuman dilemma. —D.K.

Available on Amazon as DVDs.

All you need to know to enjoy The Sopranos’ best stand-alone—yes, including “Pine Barrens,” which is Rutherford Falls showrunner Sierra Teller Ornelas’ stand-alone pick for Slate—is what you already know: Tony is a mobster and Carmela is his wife. The series’ fifth episode sets aside the show’s sprawling cast of characters to focus on its central couple, as Tony takes his daughter on a college tour, and Carmela, left at home, is tempted by her handsome priest. Just as viewers did back in 1999, the newbie will watch “College” wondering, Are these people really going to do this?—and just like in 1999, the answer to this question will be surprising, confounding, and captivating. “College” was the episode that convinced us that we were watching a show unlike anything we’d seen before; don’t be surprised if, after this stand-alone experience, you’re desperate for more. —D.K.

Streaming on Max.

The typical episode of 1990s NBC stalwart ER told a dozen medical stories at once in a whip-panning frenzy, while stretching its many characters’ continuing dramas to the breaking point. But this Season 5 episode was a welcome respite from the show’s breathtaking pace, and a lovely fish-out-of-water story with surprising relevance decades later. Ambitious Black surgical resident Peter Benton takes a two-week fill-in assignment in a small-town Mississippi clinic, where the rural health care gap has him managing diabetes care, delivering babies, and rescuing farmers from under their tractors. It’s a far cry from Chicago, but Benton (played by the underrated Eriq La Salle) finds joy and connection in the assignment, helped along by the local nurse practitioner (the great character actress Celia Weston). Corny and moving in equal measure—like all the best episodes of ER—“Middle of Nowhere” is a thoughtful, lovely hour of TV. —D.K.

Maybe you’ve avoided watching this turn-of-the-millennium series because its mythology is so dense, or because its fandom is so strident, or because its creator, Joss Whedon, has been unveiled as a borderline creep and a definite bad boss. But when you’re in the mood for a short, funny, wildly entertaining horror story, dial up this all-time great episode, in which voices are stolen, hearts ripped from chests, and secrets revealed. It’s a perfectly crafted dark fairy tale, the only Buffy ever nominated for a writing Emmy—even though, for most of the episode, no one says a word. —D.K.

Streaming on Hulu.

SpongeBob SquarePants, the long-running animated series about a porous yellow sponge who lives in a pineapple under the sea, is at its best when it leans into the surreal. In “Rock Bottom,” the second segment of Season 1’s 17th episode, the show crashes full tilt into the uncanny, taking us—and SpongeBob—from pleasant Bikini Bottom to a strange, dark place located off a 90-degree cliff far down in the ocean’s abyssal zone. Like most of SpongeBob’s episodes, this installment is more or less entirely self-contained, its short narrative easy for even the most distracted 7-year-olds to follow. But it also boasts enough edge to capture the attention of grown-up viewers: Rock Bottom, where our hero finds himself stranded for the night after getting off at the wrong bus stop, is genuinely eerie; the deep-sea creatures that inhabit the area appear appropriately eldritch; SpongeBob’s fear, as the lights flicker off and unidentifiable things go bump in the night, is both palpable and contagious. This was the first SpongeBob segment I watched, as a child, that gave me tickles of fright, and more than two decades later, it remains an unexpectedly effective snack of suspense—and a great first illustration, for kids of all ages, of the concept of Murphy’s law. —Jenny G. Zhang

Streaming on Prime Video and Paramount+.

On the surface, Futurama comes across as a zany sitcom full of convoluted plotlines, characters, and universes, but at heart, it’s a testament to grief and the ways we cope with loss and heartbreak. That may sound heady, but there’s a reason this show could strike such a sense of bittersweetness in its loony sci-fi universe, one that comes across clearly in “The Luck of the Fryrish.” This episode toggles between the past and present of protagonist Philip J. Fry (voiced by Billy West), at first displaying his childhood conflicts with his brother Yancy (guest star Tom Kenny), mitigated by the luck young Philip gains after discovering a seven-leaf clover. We then head to Futurama’s year 3000, where the adult Philip Fry, transported to this future against his will, realizes he has no luck in anything he does and searches for that old clover. “The Luck of the Fryrish” homes in on Fry’s younger years and modern-day growth, making this a less-obscure Futurama romp—it’s a focused, reflective journey into the nature of memory and familial love, one that adds up to a gobsmacking, moving conclusion. When you experience it, you’ll understand why Futurama’s fans consider it to be such a tearjerker. —N.P.

Streaming on Hulu.

There’s never been a better nature documentarian than David Attenborough, and in this episode, Planet Earth’s first, he takes on no less a subject than the entire world. He plays all the hits, from baby polar bears to baby penguins to the very best birds in the very best group of birds, the birds of paradise. But “Pole to Pole” also introduced viewers around the world to a number of then-cutting-edge nature documentary techniques that would become series signatures, from Errol Morris–style super slo-mo filmed with ultra-high-speed cameras (no one had ever seen a great white shark like this) to the zoom-outs that never end. (Just when you think that a migratory flock or herd couldn’t get any bigger, the camera keeps pulling back, and back, until you’ll swear you can see the curvature of the Earth.) Made for a moment in which, suddenly, viewers could watch nature shows at home on DVD and on newly mainstream high-definition televisions, it blew minds (only some of which were under the influence of marijuana) and launched a new golden age of nature documentaries. When it comes to delivering pure awe, this episode still hasn’t been topped. —F.W.

Streaming on Max and Discovery+.

It’s widely noted that Avatar: The Last Airbender contains one of the greatest redemption arcs of all time. Yes, Avatar is a cartoon for children, but it earned this distinction with its depiction of the character Zuko (Dante Basco), the eldest son of the warmongering Fire Nation ruler, who is hellbent on stopping our heroes. “Zuko Alone”—one of the few episodes of the series that don’t bother with the protagonist Aang’s story—is the important seed of this arc, in which our favorite hothead begins to abandon the life of cruelty he had forced himself to adopt.

“Zuko Alone” tells two stories. In one, it’s present-day Zuko’s first time being truly alone, seeing firsthand, and without bias, what his nation’s war has wreaked against innocent people. The second, via flashbacks, is our first look into Zuko’s backstory, showing how his psychopathic sister manipulated him for sport, how he lost the only person who truly understood him, and how greed for power can distort one’s judgment—a legacy of behavior Zuko was born into. The Fire Nation prince must both “move on” from his past, as he himself states, and heed his mother’s advice: “Remember who you are.” Satisfyingly, for the first time, that’s up to Zuko to decide. —Nadira Goffe

Streaming on Netflix and Paramount+.

The BBC hit series Doctor Who is notorious for its long story arcs and convoluted lore, but “Blink” is a wonderful example of what happens when the show abandons that reputation for a moment. The episode requires no knowledge of the rest of the show because the Doctor—the 10th, played by David Tennant—is barely in it. Instead, it follows the story of an outsider, someone who only briefly tangles with the sci-fi shenaniganry of the Doctor’s world. The plot has all the best parts of Who’s usual brand: It’s a genuinely interesting mystery, featuring time travel, spooky aliens, and a plucky main character (a young Carey Mulligan) to carry the story. The episode, which is widely considered to be one of the best in Doctor Who history, has no prior baggage and leaves no loose ends, making it perfectly catered to a stand-alone viewing. —Shivani Ishwar

Streaming on Max.

Plenty of Lost episodes expertly expand upon the byzantine mystery drama of plane-crash survivors who find themselves stranded on a magical island, but “The Constant” is almost better when viewed as a separate narrative hour. After island strandee Desmond (Henry Ian Cusick) experiences his brain time-jumping between present-day 2004 and 1996, he forgets everything about the island, making it easy for unacquainted audiences to follow along. However, the stakes are immediately made clear, even to new viewers: Being “unstuck in time” has put Desmond’s brain under too much stress, which will inevitably kill him if he doesn’t find something or someone—his “constant”—to anchor him to reality.

“The Constant” remains one of the best episodes of one of the most discussed television series of all time because it takes the format Lost popularized—constant twists, turns, and cliffhangers—and delivers them multiple times, before nearly every commercial break. But above all else, it tells the resounding story of a love that knows no bounds, whether it’s between friends who will believe you and protect you at your most vulnerable, or lovers who will forgive you, wait for you, and search for you in any timeline. —N.G.

Streaming on Hulu and Amazon Freevee.

Throughout its six-season run, Community was never a ratings monster, but for a time, it was one of the most inventive shows around—certainly within the realm of single-camera, half-hour sitcoms. Creator Dan Harmon delighted in pop culture references, self-referential humor, and the pleasure and subversion of well-known tropes. These strengths are on full display in “Modern Warfare,” Community’s sendup of action movies like Die Hard and The Matrix. Greendale Community College descends into dystopian chaos after the school’s dean announces a paintball war with a prize that most would kill (nonviolently, using paintballs) for. At an impressively tight 21 minutes, directed by bona fide action filmmaker Justin Lin (the man behind five Fast and Furious movies), the episode is a pastiche of all the hallmarks of the genre: the splintering into factions, the betrayal, the ambush, the final standoff, the sacrifice, the devastating reveal. The characters share a preestablished dynamic, but you don’t really have to know anything more about them beyond what you can glean from this episode. “Modern Warfare” is silly yet serious, daring yet comforting, and above all, very fun—in short, it epitomizes all of the best qualities of Community. —J.G.Z.

Streaming on Netflix and Hulu.

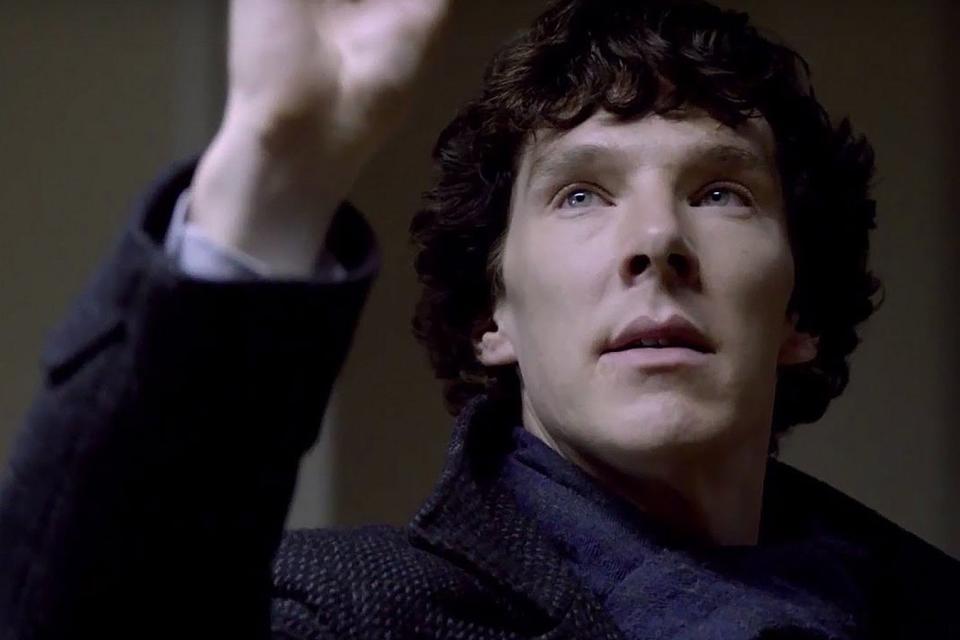

Pilot episodes, by nature of being the first, usually require no knowledge of anything that’s come before, but that doesn’t mean they always stand alone. Many sag under the burden of all they have to set up for future installments, while other shows simply take time to find their footing. Neither of these facts is true of the Peabody-winning first episode of Sherlock. Because the BBC series reimagines the adventures of Sherlock Holmes, it can presume that the viewer already has some basic level of familiarity with the character. (When this episode does bother to provide any narrative exposition, it does so with a literal wink.) If Sherlock had a problem from the start, it’s only that it was too successful: It was such a strong showcase for its two leads that it soon lost them to Middle-earth and the Marvel Cinematic Universe. (Just two years later, Martin Freeman and Benedict Cumberbatch would face off as Bilbo Baggins and the villainous Smaug.)

This episode debuts with those performances fully formed, complete with the chemistry that launched a thousand “ships.” And its mystery is a real cracker, loosely reimagining A Study in Scarlet but upping the body count, as London suffers a series of suspiciously similar “suicides.” The master of deduction, of course, solves the case before the episode ends. (Most episodes of Sherlock are stand-alones, though some of its best, including “The Reichenbach Fall” and “A Scandal in Belgravia,” either set up or resolve cliffhangers.) But rewatching the episode more than a decade later, it still manages to be shockingly suspenseful. The game is newly afoot, but it’s already clear why this show is our greatest adaptation of one of fiction’s greatest characters. —F.W.

Available for digital rental on Amazon.

Adult Swim’s sci-fi smash Rick and Morty has occupied an odd cultural silo since its 2013 debut, garnering massive popularity and furious controversy in equal measure thanks to a fervent, outspoken fan base and allegations about the inappropriate behavior of one of its creators. But Rick and Morty’s best moments, more often than not, have come about thanks to its dynamic crews of other writers and directors, who looked beyond those creators’ visions to craft immaculate television: imaginative, delightful, perceptive, and refreshingly unafraid to be the weirdest it can be, whatever form that takes. “Rixty Minutes” is an early highlight of the qualities that make the show something truly great—its pathos, its uncomfortably familiar character sketches, and its uninhibited silliness.

Presaging the multiverse craze that saturates pop culture today, “Rixty Minutes” hinges on an irresistible premise: access to an interdimensional cable network with TV shows from infinite timelines. The episode recognizes, aptly, that this doesn’t mean an unending stream of cool shit. Infinite TV can be as rotten as anything in our dimension—and it may even reintroduce alternate timelines you may wish you’d taken, to your regret. Through these channels (pun intended), “Rixty Minutes” proves both a strong introduction to the protagonists’ dysfunctional family and a belly laugh–worthy exhibit of earthly spoofs (e.g., a hyperviolent A-Team riff called Ball Fondlers, a commercial for an appliance salesman with ants in his eyes, an improvised action movie trailer in which the voice actors crack up at the end). All of which is complemented by a B plot in which the Smith family’s exposure to the televisual beyond exposes its fucked-up dynamics—and reinforces why it stays together nevertheless. —N.P.

As anyone who’s ever watched Saturday Night Live knows, sketch comedy has always been a format best suited to just that—sketches—and it’s rare for any sketch comedy to stay funny for half an hour, let alone 90 minutes. Individual sketches stand on their own; episodes rarely do. But Key & Peele was always more consistent than most sketch comedies—in addition to bringing more variety than I Think You Should Leave, hitting harder than Portlandia, and aging better than a lot of Chappelle’s Show (even setting aside all the baggage). This episode, the finale after a five-season run, shows Keegan-Michael Key and Jordan Peele going out at the top of their game. The opening pair of sketches—the first, a commercial for a CD compilation of “Ghostbusters” songwriter Ray Parker Jr.’s other, unused movie theme songs; the second, a premise that starts silly but, in a foreshadowing of Peele’s subsequent career as a horror auteur, takes a shocking turn—shows how the duo blended the silly and the surreal. They’re both great sketches, but the episode’s most famous sketch is, justly, its last: “Negrotown,” a Technicolor, Busby Berkeley–esque vision of a fantastical Black utopia where, for example, “You won’t get followed when you try to shop/ You can wear your hoodie and not get shot.” It was a dark parting statement from a show that was at times wrongly held up as an example of cuddly, “post-racial” comedy, one that makes you laugh and then makes you wonder whether you should. —F.W.

Streaming on Netflix, Hulu, and Paramount+.

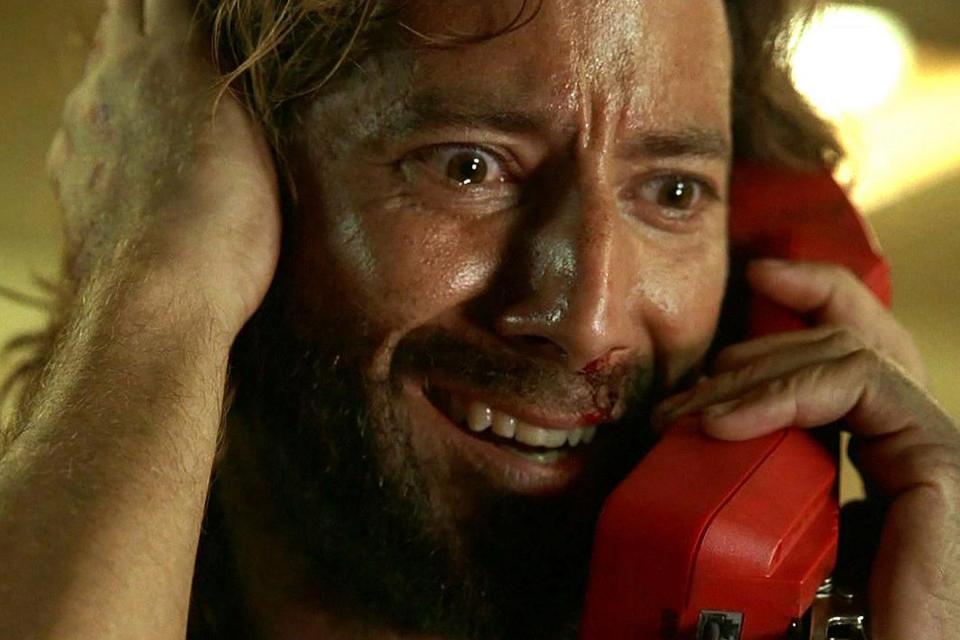

The Leftovers, a loose adaptation of the eponymous Tom Perrotta novel in which an inexplicable event causes 2 percent of the world’s population to randomly vanish, is a great example of showrunner Damon Lindelof’s usage of surrealism in parsing out life’s biggest conundrums. This is best seen in the episode “International Assassin,” which steps away from the main plot to interrogate the inner workings of protagonist Kevin Garvey (Justin Theroux).

“International Assassin” is a masterful puzzle. When Kevin wakes up in a full hotel bathtub, completely naked, he’s just as confused as we are. The hotel is some sort of afterlife, and in order for Kevin to return to the living, he must solve some riddles that not only reveal truths he’s been hiding, but also force him to make decisions that will define his future. Partnered with a standout performance from Ann Dowd, Theroux gives us some of his best work on the show, as Kevin attempts to grapple with these riddles. You can spend hours debating what the episode really means, but it’s a beautiful exploration of The Leftovers’ main themes: grief, guilt, identity, letting go, and making difficult but necessary choices. —N.G.

Is it possible to raise Black children within a truly safe, happy bubble and still prepare them for a harsh world? Years before George Floyd’s death in 2020 would spark an unprecedented level of global backlash to the state of U.S. policing, the sitcom Black-ish tackled this question. Reminiscent of a one-act play, “Hope” finds the Johnson family in their living room as they await the grand jury decision in a highly charged case of police brutality against a Black teen. As the news unfolds, parents Dre (Anthony Anderson) and Rainbow (Tracee Ellis Ross) debate whether they should spare their family the details to protect their children’s sense of hope, or choose to explain the harsh reality of being Black in America.

The episode still manages to be a funny half-hour of TV (there’s a Black Panther–adjacent joke invoking a different “radical cat family” that had me in the happy kind of tears), while also exploring so much of the conversations and emotions that Black people have about policing. A lesser episode of television would pose the critical question and evade an answer, but “Hope” skillfully comes to a devastating, yet necessary final stance: Innocence is a privilege that not all children are afforded. —N.G.

Streaming on Hulu and Disney+.

BoJack Horseman, one of the best TV shows of the 2010s, was a vibrant yet nihilistic animated series about alcoholism, abuse, and exploitation. The show put in its crosshairs the violent churn of Hollywood and the egomaniacal monsters it creates. BoJack also featured characters with the bodies of human beings and the heads of animals (see: the titular horseman). The psychedelic dissonance of the show’s form and content is what made it so brilliant: It was the kind of show that could realistically depict the disorienting misery of a drug-induced bender while also maintaining a multiseason lowbrow joke about the D being stolen from the Hollywood sign. (Every character called their company town “Hollywoo” going forward.)

But “Fish out of Water” was really something special. Sent underwater to promote his new awards-bait biopic, BoJack embarks on a pensive, nearly dialogue-free Technicolor aquatic adventure in which he seeks redemption with a former colleague, brings new life into the world, and gets a taste of the utterly isolating existence of being a prestige celebrity. The main thrust of the plot—in which BoJack assists a sea horse in giving birth and then must help reunite one of the newborns with that father—is a deceptively simple but altogether affecting meditation on family and loneliness. Creating an almost-dialogue-free episode is an impressive feat on its own, but even setting aside that remarkable aspect, “Fish out of Water” is an exemplary stand-alone episode, one with the most emotional—and the sweetest—moments contained within a deceptively small conflict. —Madeline Ducharme

Streaming on Netflix.

High Maintenance is a tough show from which to choose one great stand-alone episode, although it consists nearly entirely of them. Maybe that’s because it got its start as a web-only series, with six gem-packed seasons I’m leaving out for the purposes of this list. But even when you narrow it down to the four excellent seasons that ran on HBO from 2016 to 2020, the show’s variable narrative structure eludes any attempt to highlight a typical episode. Since the premise is that the not-quite-protagonist, a nameless weed-delivery worker known only as The Guy, weaves in and out of the lives of different New Yorkers each week, no episode quite resembles the last—except in their shared bravura of direction and writing, offbeat casting, cheeky sense of humor, and remarkably expansive sense of compassion. The show’s co-creators, Katja Blichfeld and Ben Sinclair (who also plays The Guy), used the move from the web to TV to experiment with new forms of visual storytelling, resulting in episodes like the playful-yet-heartbreaking “Grandpa,” the story of a neglected dog as seen from the dog’s point of view. The initially droopy Gatsby (played by a soulful gray poodle mix named Bowdie) starts to find his mojo when his depressed owner (Ryan Woodle) hires an affectionate and—not for nothing—sexy new dog walker (Yael Stone). By the standards of the usually chatty High Maintenance, “Grandpa” is light on dialogue, with the human stories unfolding only through the scrim of a dog’s understanding. But the creators’ innovative use of framing and editing to place the viewer inside an animal’s consciousness makes it the perfect jumping-off place for a High Maintenance deep dive. —Dana Stevens

Streaming on Max.

Black Mirror is an anthology show, meaning that every episode is a stand-alone. A great many of them are excellent—“The Entire History of You” and “Hang the DJ” are two others that come to mind—but it’s still surprisingly easy to pick the best one from a long list: Obviously, it’s going to be the only episode to star the wildly appealing Mackenzie Davis and the radiant Gugu Mbatha-Raw in a revolutionary queer love story. The 1980s setting, soundtrack, and costumes make for an irresistible backdrop against which Davis’ shy Yorkie falls for Mbatha-Raw’s vivacious Kelly. This is Black Mirror, so of course there’s a futuristic twist (one that’s way more clever than the many copycats it inspired, by the way)—as it turns out, the two women’s queerness is far from the only reason their romance may be star-crossed. The episode’s ending, set to “Heaven Is a Place on Earth,” is note-perfect. Even long after you’ve finished watching this episode, you’ll feel its impact elsewhere across television, in the myriad other on-screen same-sex romances that it helped usher in. —Heather Schwedel

Streaming on Netflix.

In one of her most inspired bits of guest-star casting, in the sixth and final season of Girls, creator Lena Dunham plucked Matthew Rhys out of The Americans, where he was midrun as conflicted spy Philip Jennings, and plopped him onto her show for a one-episode turn as Chuck Palmer, scraggly great male novelist and accused sex pest. After Dunham’s Hannah Horvath writes a blog post denouncing Palmer’s penchant for coercing college-aged women into the bedroom, Palmer invites her to his well-appointed Upper West Side abode in an attempt to win her sympathies. They talk, they spar, and they eventually find some common ground—or that’s where it seems as if things are going, right up until Chuck takes out his penis and wantonly flops it onto Hannah’s thigh, showing her he has been playing a different game the whole time. This aired, by the way, months before the #MeToo movement gained mainstream traction. “American Bitch” is one of several of the show’s excellent one-off episodes that demonstrate Girls at its daring, stylish, unmissable best. It is, as Search Party co-showrunner Sarah-Violet Bliss writes in her own stand-alone selection for Slate, a sublime bottle episode “that has nothing to do with the rest of the show, but everything to do with the rest of the show.” —H.S.

Streaming on Max.

Master of None, a day-in-the-life comedy about a struggling actor (played by Aziz Ansari) in New York City, is best when exploring dynamics that are specific to a character but also indicative of a larger systemic problem or cultural expectation. “New York, I Love You” does not concern itself with the usual cast of characters, instead focusing on the lives of three everyday New Yorkers. There’s Eddie, a Latino doorman whose daily interactions on the job begin to demand too much of him; Maya, a Black deaf woman who is trying to reclaim some sexual agency in her relationship; and cab driver Samuel, a Burundian immigrant who tries to strike a good work-life balance. Expertly interwoven with the opening of a fictional film called Death Castle (starring Emma Watson, Tyrese Gibson, and Nicolas Cage), “New York, I Love You” fully immerses the audience in the lives of these New Yorkers—using an especially smart technical trick to do so for Maya’s section—while also subtly commenting on the ways in which race and class affect many of us. —N.G.

Streaming on Netflix.

A stand-alone episode usually qualifies as one because it contains within itself everything you need to understand it. Twin Peaks: The Return’s “Part 8” is great because it doesn’t. A surreal, nightmarish interlude that’s as close to abstract art as anything ever broadcast on commercial television, the episode defies all but the most tentative of explanations—but rest assured, stand-alone viewer, that Twin Peaks obsessives were no less at sea than you are. It might help to recognize the faces of Laura Palmer, the hard-partying high schooler whose murder kicked off the original series in 1990, and Bob, the menacing evil spirit responsible for her death, but they appear only fleetingly here, as embodiments of good and evil whose nature can be inferred at a glance. Winding back the clock to the first atomic bomb explosion in 1945, David Lynch doesn’t need a giant screen to make its impact felt, just the shrieking dissonance of Krzysztof Penderecki’s score, which not only splits eardrums but seems to rip apart the fabric of reality itself. Men with soot-smeared faces flicker into being, mysterious insects are hatched in the desert, and that’s only scratching the surface. You won’t often know what you’re looking at, but if you can let go of the need to, you’ll be blown away. —S.A.

Streaming on Showtime and Paramount+.

“Finding Frances,” the last and longest episode of Nathan for You, feels like no other episode of the gimmick-happy, consultancy-mocking comedy under which it aired. Instead, it’s a unique document with a life all its own, a lovely oddball saga incomparable with anything else on TV (except, perhaps, for co-creator and star Nathan Fielder’s latest mind-bending experiment, The Rehearsal). The episode’s plot does rely on a previous Nathan for You installment, but that’s not important; what is important is that that episode got Fielder to befriend a “professional Bill Gates impersonator” named Bill Heath, who in the present day keeps alluding to a former lover named Frances Gaddy. Even though it’s been 50 years since Bill and Frances lost touch, and there’s little information at hand, Nathan is determined to “use the resources” of his show to find her so that Bill can profess his love and regret.

However you perceive that description, I can promise you that the story—which is mostly real—does not go in any direction you could imagine. It’s a love story, albeit not the one you might anticipate; it’s a road trip adventure, although its most exciting journey is more introspective than geographical; it’s a comedy, but your laughs will likely stem from nervousness or pleasant surprise; it’s a reality-TV quasi-documentary, but the emotions don’t feel so over-the-top. “Finding Frances” takes the remarks of a lonely, wistful old codger and reveals from there the totality of one human being, and of those around him—their desires, costumes, lies, expressions, deceptions, vices, worldviews, and memories. And from there, it provides a window into how any one of us can take stock of our life and, hopefully, make it a little better. —N.P.

Streaming on Max and Paramount+.

Brooklyn Nine-Nine’s essential bottle episode “The Box”—which centers only on Detective Jake Peralta (Andy Samberg) and Captain Holt (Andre Braugher) as they try to wrangle a murder confession out of a meticulous dentist (guest star Sterling K. Brown) overnight—is the greatest isolated episode that the cop workplace comedy has to offer. Not only does it focus on one of the show’s best relationships, that of blossoming mentor-mentee duo Holt and Peralta, but it also throws in a stellar performance from Brown, who acts as the straight man to the detectives’ antics—so stellar that it netted Brown an Emmy nomination. The comedic timing is, as always with Nine-Nine, on point—a miraculous feat, considering that the episode contains a lot of very good, incredibly quick dialogue for 22 minutes of TV. But make no mistake, Brown gets in on the jokes too. In fact, the whole episode is worth watching for a singular joke in which Brown’s character, with a straight face, is forced to say the victim’s name a myriad of times in myriad ways. —N.G.

Streaming on Peacock.

Ramy, one of the greatest shows on television (and certainly on Hulu), primarily follows the titular character, a first-generation American Muslim man reconciling his heritage with the messy melting pot of New Jersey. But the stand-alone episode “Ne Me Quitte Pas” (French for “don’t leave me”) has very little Ramy in it; instead, it zooms in on his mother, Maysa, played by the astonishing Hiam Abbass. Maysa, who spends her days hovering outside the window of an aerobics class, cooking and waiting around for her family, and scrolling on Facebook, clearly feels adrift, worried that she’s lost herself to her duties as a mother. She becomes a Lyft driver, and in doing so, connects with a French stranger who calls her company an “oasis,” offering a rare sense of joy in a life that otherwise feels more like a revolving door between sets of family chores.

What’s so special about this episode is how it explores one character so deeply, critically and bravely taking on the cultural nuances of an Arab migrant mom living in America with American kids. This episode is also remarkable for the way it refuses to allow an overlooked member of the Hassan family to fade into the periphery: While other characters go about their own adventures, this snapshot forces us to stay in the house and in the mind of the mother whose responsibility it is to do the grocery shopping, prepare the meals, and clean it all up afterward. It does an exemplary job of making the viewer conscious of Maysa’s loneliness and desire for freedom, without veering into the realm of boring or preachy. It’s a powerful portrayal, one that will alter the way that any viewer thinks of their own family dynamics—it certainly did for me. —Aymann Ismail

Streaming on Hulu.

Barry was always a little dreamlike, in the sense that it asked us to imagine such a thing as a softie hit man with newfound thespian aspirations and the extremely nonthreatening visage of, well, Bill Hader. The bulk of the series coiled layers of gut-squeezing tension, episode by episode, as Barry dug his own grave. But in “ronny/lily,” which arrives halfway through the second season, all of that is put on hold for Hader to create his own little psychedelic action movie, one that requires blessedly little context to watch unfold.

Barry has taken on a kill contract, which he would like to accomplish without hurting anyone, and he’s run afoul of Ronny, a nunchuck-wielding taekwondo master with supermodel good looks, and—the star of the episode—his unhinged, feral daughter Lily. The trio engage in an elliptical, almost ASMR-like fight sequence that ends with the preteen perched on top of her suburban home—like an Angeleno Batman—as dusk falls. There is almost no dialogue throughout, and due to his blood loss, Barry constantly slips in and out of consciousness, which only adds to the delirium. You’re left thinking that Lily is still out there, the apex predator of this universe. (It’s a bummer that we never get to see her again.) For a series that grew ever more cerebral and ambiguous throughout its run, often at the expense of its comedic roots, regular viewers might find it nice to look back on this episode and remember when Barry was funny. For everyone else, it’s a self-contained parcel of perfect slapstick, a feat of direction, physical stunt work, and the sublimely weird experimentation that will remain the show’s legacy. —Luke Winkie

Streaming on Max.

The belief that the 1995 animated Disney film A Goofy Movie is actually a Black coming-of-age story is a widely accepted inside joke that most Black kids who grew up on the film know to be true. Despite the film’s mostly white cast, you can point to many things that hint at the movie’s underlying Blackness—for example, Goofy’s son, Max, being compared with a gang member because of his baggy clothing. These idle speculations are cemented as reality in Atlanta’s mockumentary-style “The Goof Who Sat by the Door,” our pick for the best stand-alone episode in a series that’s chock-full of them (see also: “Teddy Perkins,” “The Club,” and “Crabs in a Barrel,” as selected for Slate by TV veterans Lila Byock, Amy Aniobi, and Patrick Somerville).

The episode, which takes its name from Sam Greenlee’s The Spook Who Sat by the Door—a novel about the fictional first Black CIA officer—breaks away from all previously established worlds, characters, and formats to tell the invented story of Thomas Washington, a Black animator who became the CEO of Disney and endeavored to make “the Blackest movie of all time,” resulting in A Goofy Movie. It’s so technically on the nose, from its measured pacing to its talking-head interviews with real journalist Jenna Wortham and actor Sinbad, that it almost convinces you it’s real—until a line of slang or overwrought references to the Green Book and Jim Crow remind you that it’s all an elaborate joke. “The Goof Who Sat by the Door” excels at its aim so much it almost makes me resentful of the fact that Black people have made one of our most well-kept jokes so accessible to the masses. —N.G.

Streaming on Hulu.

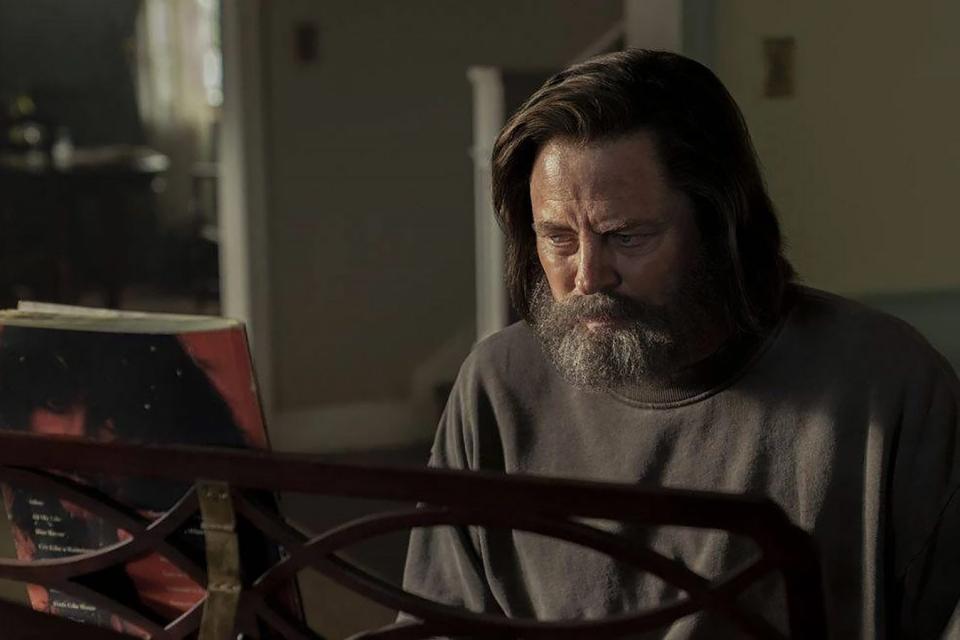

In “Long, Long Time,” The Last of Us departs from its main narrative to offer snapshots of an unlikely romance blooming in a hostile climate. In a postapocalyptic world ravaged by a zombifying fungus, survivor Frank (Murray Bartlett) stumbles upon Bill (Nick Offerman) in the latter’s rural prepper compound, where he’s planned to ride out the collapse of civilization alone. But the two soon fall in love (Bill discovering his gayness in stride) and quietly, organically take on the task of preserving some of humanity’s better impulses—painting and gardening, cooking and music—within their fortified hamlet. As I previously wrote about the achingly poignant—and, given its queerness, politically urgent—episode: “By the end of their story, these men have transformed their lives and their small domain into a kind of artwork, a site-specific installation on the themes of human creativity, sensuality, and love in the midst of rubble and rot. This is their achievement. This strange, absurd, wasteful, astonishing project—making more beauty in a world consumed by ugliness—is what they have spent their resources and energy and years on this benighted planet doing.”

The burly couple, in this stand-alone vignette of their lives together, bring an hour of grace to a show that could easily have been consumed by fungus and fear. The Last of Us was criticized in some circles for its penchant for lyricism over action, but it’s hard for me to imagine watching the ballad of Bill and Frank and not understanding the value of this choice, even at the end of the world. In the midst of humanity’s worst nightmare, it’s a powerful thing to dream, just for an episode, of two of us at our best. —B.L.

Streaming on Max.

When Vanderpump Rules began airing its 10th season earlier this year, what had started out as a reality show chronicling the messy lives of twentysomethings working at a West Hollywood restaurant owned by a Real Housewife was struggling to stay compelling, its remaining stars having outgrown the initial premise. Then a cheating scandal broke, becoming national news and reinvigorating a show that has always thrived on sex, lies, and videotape. Bravo moved quickly to go back into production and capture the aftermath of longtime cast member Tom Sandoval cheating on his girlfriend of nine years, Ariana Madix, with fellow castmate Raquel Leviss, and the resulting hour is a transfixing episode of television. It obviously carries a lot of payoff for longtime viewers, but the episode is also fascinating in its own right as the culmination of months of headlines, weaving in years of backstory and fourth wall–breaking footage to deliver a full anatomy of the scandal. Madix’s self-possessed and articulate kiss-off speech to her ex is a thing to behold—emotionally cleansing for anyone who has experienced such a betrayal—just as Sandoval’s and Leviss’ excuses are galling. The whole thing is an argument for reality TV as art form, no matter how familiar you are with the players involved. —H.S.

Streaming on Peacock.

Want more stand-alone episodes? Here are 11 additional recommendations from some of our favorite TV writers and showrunners, including Abbott Elementary’s Quinta Brunson, Station Eleven’s Patrick Somerville, and more.