These 3 sisters spent a collective 93 years serving on Christian County school boards

Their mother so valued education that she was a constant presence in their classrooms. Their father urged them to get involved and become the change they wanted to see.

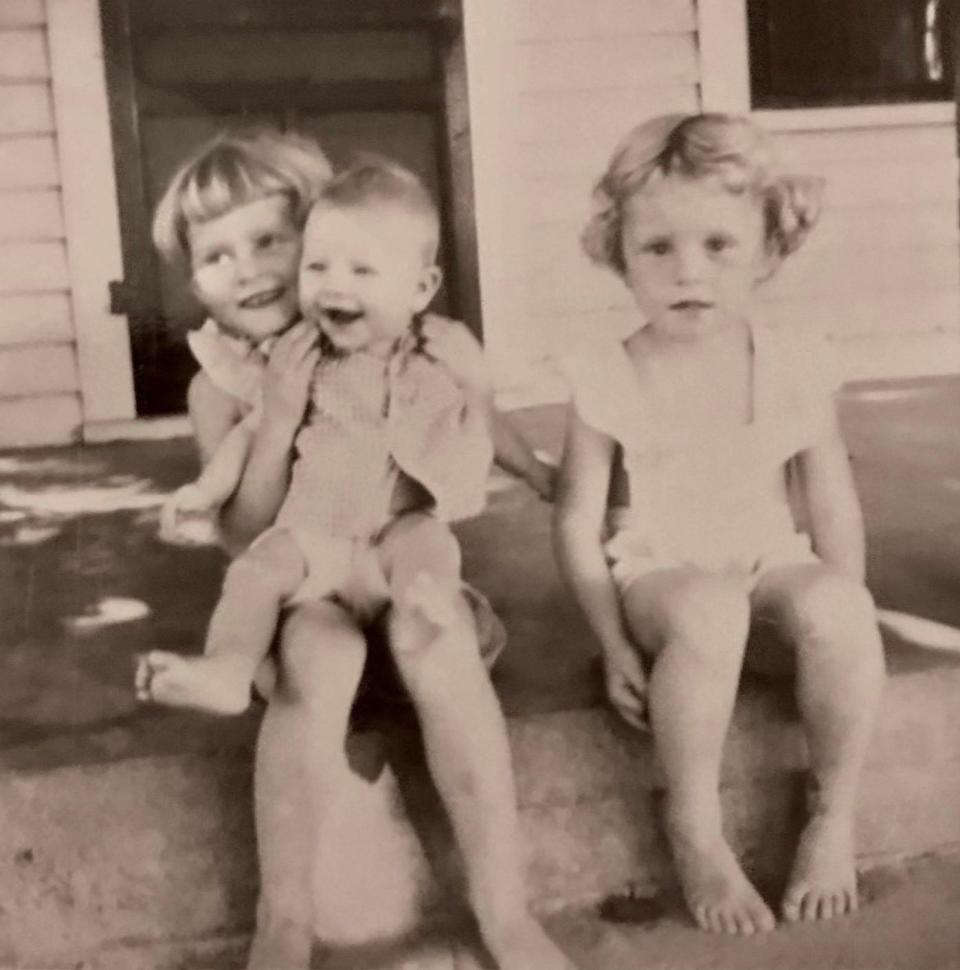

Inspired by that example, the three daughters of Lester and Lela McPherson — Betty Braden, Peggy Taylor and Patty Quessenberry — devoted their lives to supporting and championing public education. They've collectively spent 93 years serving on school boards in Christian County.

Taylor spent 30 years on the Nixa school board, stepping away in 2015. Braden retired from the Sparta school board in 2021 after 36 years.

This week, Quessenberry — who lost her reelection bid April 2 — completed 27 years on the Ozark school board.

"Their parents created a passion for public service in their children and it has served Missouri well," said Melissa Randol, executive director of the Missouri School Boards' Association. "There are no greater advocates than the three of them for children."

Randol said while Braden, Taylor and Quessenberry spent their time serving the students, teachers and parents in their communities, they have also had an impact at the state level.

"It is extraordinarily rare for an individual to serve as long as each of them have and then, collectively, I don't know of another situation in Missouri, at the local level, where we've had family members who have given as many years as those three extraordinary women have given," Randol said.

"We're all fortunate. We've all benefited from their service because they are not motivated by doing anything other than what is right and best for Missouri students."

"Memory of what we saw as children"

The three sisters, and their three brothers, grew up in Christian County. They were raised by their father, a veteran who farmed and drove a truck, and their mother, who was widowed in 1978.

The couple supported their children, and the school, any way they could. They attended pie suppers and Lions Club and PTA meetings.

"Mom was a homeroom mother. She'd come in carrying cupcakes or whatever and you were just so proud to see your mom in the school," said Braden, 73. "That was one of the things that made all of us want to be involved for our kids, was the memory of what we saw as children."

Their father ran for school board one year. He wasn't elected.

Braden is the oldest, followed by Taylor, and Quessenberry is the youngest. All three sisters served as valedictorians at Sparta High School.

Each married, had children, and volunteered in the classrooms of their sons and daughters. All three got involved in the PTA, rising up through the ranks to become president.

Braden said they inspired each other. "You see what the other ones are doing for their school, or trying to do, and so you get involved."

They represented the PTA at school board meetings. At the time, the boards were mostly filled with men.

"For two years, I sat and watched ... what was not truly active involvement from board members. I thought, 'Our school deserves better than this,'" recalled Taylor, 72.

Watching as a PTA liaison, Quessenberry said she felt the board would benefit from "a mother's voice."

Braden and Taylor, long-time co-owners of Dogwood Printing in Ozark, were first elected to a school board in 1985. Quessenberry, who worked at Kraft Foods in Springfield, won her seat in 1997.

"Betty and Peggy kept encouraging me 'Put your name in' and so I did, 12 years after they'd been on there, I put my name in the hat and got elected," said Quessenberry, 69.

In Missouri, most school board members serve three-year terms but elections are staggered with two or three seats on the ballot each year.

"What's funny is every three years, all three of us were up. The same year," said Quessenberry, adding that it made Election Day more fun. "A lot of times, we were at the courthouse together waiting for returns to come in because it was all Christian County voters."

Facing new challenges, superintendents

Through the decades of board service, the sisters encountered many challenges. They faced tight budgets, teacher and staff turnover, complicated construction projects and difficult decisions.

Braden, Taylor and Quessenberry each served as president of their respective school boards at least once.

The three sisters collectively worked with more than 15 superintendents and noted some were more effective than others.

Braden, who was affectionately referred to as the "mom" of the Sparta board, said the district had seven leaders during her tenure.

She said the turnover was often bittersweet but she supported their career goals and wished them well. "Most of them were brand new superintendents and helping them, guiding them, having friendships with them, and being their listening boards ... and then watching them ask for a letter of recommendation so they could go on to a bigger school district."

Braden added: "They're influencing so many more kids because of having been at Sparta than I could ever imagine. It is just so rewarding to see what they've done."

Over the years, Braden said she was told how many educators fondly recalled their time in the district. "A lot of our teachers come in brand new and they get a few years of training and then they go on but there is always that Sparta connection."

She said there are strict laws that limit how much information districts can release about personnel issues and there are times changes can not be explained publicly.

"Sometimes you feel like friends turn against you overnight because of something they perceive that you've done wrong when, if they knew the truth, they would not be upset with you," Braden said. "That just breaks your heart sometimes to feel like you've hurt somebody you care about but you got to do what is best for kids."

Taylor said managing growth was a construct struggle during her years in Nixa.

"We were seeing 300 new students a year, we were opening a building every two years," Taylor recalled.

She said as new families moved into the area, taxpayers stepped up. They repeatedly passed tax levy increases and bond issues. "What was so overwhelming was the support that we had from our community. They wanted to invest in education."

More: Fueled by bond funds, Nixa Public Schools enters busy summer of planning, projects

For Quessenberry, the toughest period was during the global pandemic. She said the rapidly developing situation meant the board, and district, were trying to listen to parents and employees as well as evolving advice from local, state and national health experts.

"We were scared ... people were dying and we were trying to make decisions and some of the public was mad at us because we were requiring masks and requiring vaccinations. They still hold that against us," she said. "I just wanted our kids to be safe. I wanted our teachers to be safe and I wanted to get them all back in a school building."

Quessenberry said school officials tried to make the best decisions possible during an unprecedented situation and there was a silver lining. "It pulled us together stronger ... as a board just because of the challenges we had during that time."

"Investments you make in individuals"

The sisters were on school boards long enough to see their own children graduate, as well of hundreds of additional students they felt a responsibility to serve.

Quessenberry, who has two children, has two grandchildren now in school. Braden has three children, six grandchildren and one great-granddaughter. Taylor has three children, six grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

"My son graduated in 2000, my daughter in 2001 and then the next year or two, my term was up for re-election. My daughter goes 'Why are you filing again? We are out of school,'" Quessenberry recalled, with a laugh. "I said 'Nope, I still have, at that time, 5,000 kids in school I have to stand up for.'"

Asked what kept them serving so long, all three sisters said it was the students and teachers they saw develop and grow.

Taylor and Quessenberry said they were especially proud of supporting alternative programs in their districts to give high school students a different path to earn a diploma.

"To see the 500th student that had graduated through that program, I sat and cried," Taylor said of Nixa's SCORE, which stands for Second Chance of Receiving an Education.

More: Nixa Public Schools outperforms regional peers, most of Missouri in annual report card

Taylor said any mention of the program makes her think of a local businessman, who now operates in several states, who said he was able to graduate because of that option.

"His image always comes to me. He made the success because we stood behind the program. Our board believed in that program," she said.

Taylor said alternative and early childhood education are expensive because they don't draw down enough state aid to cover all the costs. She argued both pay off for the entire community.

"It is investments you make in individuals," Taylor said. "You see them with their needs and their goal and you help them achieve it."

All three sisters were heavily involved in the Missouri School Boards' Association, with Taylor serving as president. As president-elect of MSBA this year, Quessenberry was set to move into the president role for the 2024-25 year.

Braden, who received a service award from MSBA, said Sparta board members benefited greatly from training that was provided by the association. She said networking with school boards in other parts of the state also provided a wealth of new ideas.

"That helped our board see what we could be doing and to exercise that and put that into our school," Braden said. "As Patty and Peggy talked about, we did credit recovery ... and we've added different kinds of classes that we didn't ever think about having before and that has really helped our kids in different areas."

Looking back, Braden said it was the small moments that meant the most to her.

"As school board members, you go walking through the halls of the school," she said. "I remember this one day, this little girl came up to me and she took my hand and walked with me. I thought 'This little girl needed attention' and she trusted me to give her that. It is a feeling you carry throughout your career as a school board member that 'I am making a difference in the life of children.'"

How board service has changed over the years

Braden, Taylor and Quessenberry said the trappings of school board service changed during their long tenures.

At the time Braden started in 1985, Sparta had about 35 pages worth of district policy. "Now there are more than a thousand pages of policy and trying to keep up with all that has been something."

Quessenberry was elected the board secretary and treasurer. In that role, she had to sign all of the checks sent by the district.

"They kept me on for two or three years. Finally I said if I am going to have to do that, can I get a stamp?" she said. "They actually made me a stamp with my signature and I had to go through and stamp each one."

Early on, the three received thick packets or binders of the board meeting agendas and all the related documents to be reviewed or voted upon. It would arrive by mail or courier.

"I remember those huge packets," Taylor said. "Sometimes they wouldn't mail them, someone would deliver them to the house, because of the cost of mailing them."

In recent years, the board documents are online and that is also how votes are cast and recorded. More districts are also recording and posting videos of the meetings.

Taylor said the biggest change for current board members is the political environment. She said issues have become more divisive and there is less respect for elected officials and the process.

"It should be nonpartisan because it is what is best for kids and you can never compromise that part," Taylor said. "I know board members in the last few years tell me it's not fun anymore ... And that is not just Nixa, that is in school districts around the state."

More: Outbursts at meetings prompt Ozark school board to approve new rules for civility

Parents in Missouri and across the U.S. became more vocal during the pandemic and there have been political and outside spending groups trying to influence the outcome of elections.

Pandemic-related learning loss, teacher and staff turnover, and student discipline have also raised tough questions.

The sisters said there are also a lot of misconceptions about what it means to serve on a school board and they have intensified over time.

"They think we run the school and we don't. We have one employee and that is the superintendent. Yes, we monitor a lot of things, everything," Taylor said. "But if we're managing something, we're doing it all wrong."

They said parts of the public also believe the superintendent tells the board what to do, not the other way around. They said the superintendent serves as the CEO of the district, managing the day-to-day, and communication with the board is critical.

Braden said when the board takes a vote, the majority wins and those who voted the other way are expected to respect that outcome.

"You are ethically bound to support the majority decision," she said. "Whether you agree or don't agree, you have to support the whole board. The majority rules."

More: At town hall, Ozark school board answers questions in effort to connect with parents

Quessenberry was the last remaining sister to serve on a Missouri school board. But if she follows the examples of Braden and Taylor, she is not done supporting public education.

In Sparta, Braden has become the unofficial school historian and works closely with generations of alumni to plan the all-school and 50-year class reunions.

Taylor transitioned off the Nixa school board and serves on the Missouri Charter Public School Commission. She was first appointed in September 2014.

There is an early childhood center in Nixa named in Taylor's honor. In the Sparta district, as new schools were built or older ones expanded, plaques were placed with the names of school officials at that time.

For Braden, the nameplates are a reminder of the legacy left by each board member. She revisits the plaques when she is in a building.

"Sometimes, when I go by, I touch my name on the wall, like 'Betty is going to be here a long time — even when I am gone.'"

This article originally appeared on Springfield News-Leader: End of era: Christian County sisters served 93 years on school boards