After 23 years, wrongfully convicted man is freed in NC with aid from Duke Law students

A man spent half of his life in a North Carolina prison after being wrongfully convicted of a crime he didn’t commit, say lawyers who represented him.

The evidence that suggested Quincy Marquies Amerson fatally hit a 7-year-old while driving in 1999 was invalidated by an accident reconstruction expert hired by North Carolina.

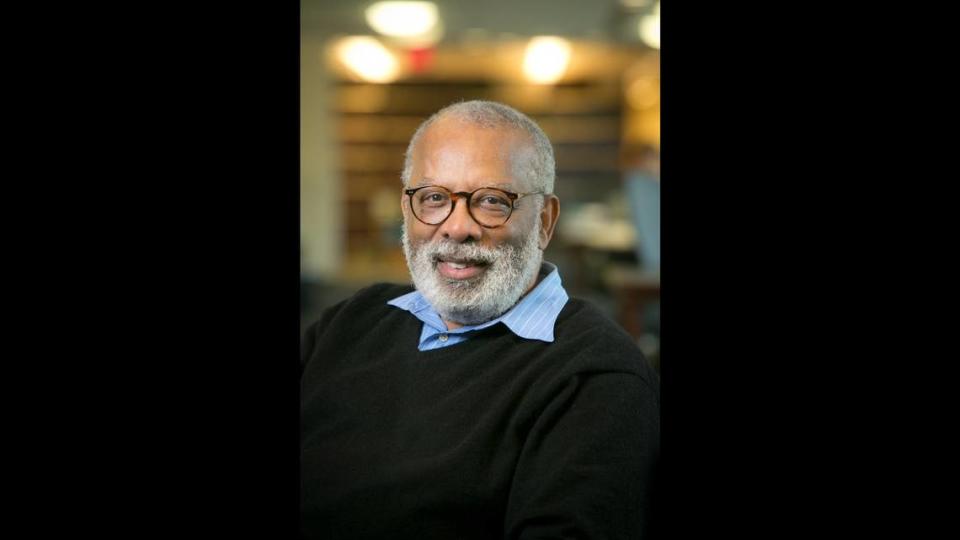

At 49, Amerson, a Harnett County native, was exonerated in February after a Duke Law School professor, James Coleman, and his students in the university’s Wrongful Convictions Clinic presented evidence challenging his 2001 murder conviction.

He had spent 23 years in the Harnett Correctional Institution.

Though absolved of the crime, Amerson spent another month in the Harnett County jail before District Attorney Suzanne Matthews finally dismissed the case, allowing Amerson to walk freely again. He went home to his parents.

The accusation and evidence

Amerson was accused of killing Sharita Rivera after she was found dead on Aug. 7, 1999, on a dark country road in Johnsonville, a small town in Harnett County. A few miles from the scene, the body of her mother, Patrice, then 24, was found stabbed 22 times in their home.

By the time police found the child, she had been struck by multiple cars. The case’s evidence relied mostly on the police officer’s initial assessment and the testimony of a Harnett County state trooper who conducted an accident reconstruction that was used to convict Amerson.

Amerson lived two houses down from the Riveras and told police he had driven on the same road the night 7-year-old Sharita was hit. The car he was driving had blood and tissue from the child on it and was missing a wheel liner.

No other evidence linked Amerson to the case.

“The most shocking thing in the case is the fact that Sharita Rivera’s mother had been murdered, and no one was ever arrested for that homicide,” said Jamie Lau, supervising attorney for the Wrongful Convictions Clinic. “It was clear that there wasn’t sufficient evidence at all that Quincy had any involvement in that or, of course, he would have been charged.”

Lau said the most logical reason the child was out on the dark road was that she was fleeing violence at her home. That’s what Shawn Harrison, a forensic engineer and accident reconstruction expert hired by Coleman, testified at the trial in 2020. The defense concluded that her death was probably the result of an accident.

Harrison said in his report that the the state trooper’s testimony and evidence used to help convict Amerson was “nothing more than speculation aided by junk science.”

Amerson, who was 24 at the time of his arrest, told WRAL Thursday that he always remained optimistic.

“I never gave up hope. I had loved ones who were along for the whole ride,” he said.

“They never, ever had any probable cause’

When Coleman first began representing Amerson in 2006, all he knew was that a man had been convicted of the murder of a little girl.

Sharita lived in Harnett County with her parents, who served in the U.S. Army. Her mother was stationed at Fort Liberty in Fayetteville, and her father, Jose, was serving overseas at the time she and her mother were killed.

During an initial assessment of the scene, police found blood and body tissue, tire imprints near the road, and the remains of a wheel liner a quarter-mile away. Because Amerson’s car also had this evidence and was missing the wheel liner, they concluded he was to blame.

Coleman said at the time Amerson was arrested, the state did not know other cars had also run over the girl.

“We also knew that in order to convict him a prosecutor got a North Carolina State Highway patrolman to reconstruct the homicide based on evidence collected, and we immediately thought that was bogus,” he said.

Coleman, who has taught criminal law at Duke Law School since 1996, said Amerson was the first driver police spoke to after the incident, and no one tried to determine if other cars were involved. His request for prosecutors to hire a new, credible expert to examine the case was repeatedly denied despite evidence collected by Coleman showing Amerson was innocent, he said.

Coleman said he wrote former Harnett and Lee County District Attorney Vernon Stewart in 2016, asking the state to hire a new accident-reconstruction expert. Then, he wrote Attorney General Josh Stein with the request in 2017 and 2018.

All the letters were ignored, Coleman said.

The state did not hire a new accident reconstruction expert until January. The expert testified in court that month that the state trooper’s claims were unsupported, causing the state to lose its evidence used to keep Amerson in prison.

“They never, ever had any probable cause that he killed the little girl, and the idea that they could convict him of premeditated murder in the case was just outrageous,” Coleman said.

Wrongful Convictions Clinic

Amerson is the 11th person to be exonerated with the help of the Wrongful Convictions Clinic, where Duke law students are supported by supervisors, outside counsel, and other professionals to help free innocent people incarcerated in North Carolina. The majority of the men exonerated through the clinic have been Black, as are the majority of people exonerated in the state.

Innocent Black men are seven times more likely to be convicted of murder than innocent white men, according to a study by the National Registry of Exonerations. Though they make up only 13.6% of the U.S. population, Black men also make up 53% of the 3,200 exonerations in the registry.

Coleman said Duke’s clinic tries to avoid arguing race being a factor in cases because “everybody’s going to be trying to show that they aren’t racist and race isn’t a factor, and you end up having meaningless discussions.”

“I don’t have any doubt that race was a factor (in the case),” Coleman said. “I believe Quincy was the only Black driver. ... They assumed that all of the evidence they saw was left by a single car and that was wrong. The prosecutor had to know that was wrong.”

Coleman said while he is proud of the work of the clinic and students, he is still upset the state, prosecutors, district attorneys and the Attorney General allowed Amerson to stay in prison as long as he did.

Buying clothes, getting a Social Security card

Since his release two days ago, Amerson has been working on getting a cell phone so that people can contact him, Lau said. The News & Observer was unable to contact him on Friday.

Amerson told Lau that he went to the Social Security office in Harnett County on Thursday to get a copy of his Social Security card and went to Walmart with his father to buy new clothes.

Next steps include filing a Pardon of Innocence request to the governor’s office. If a pardon is granted, Amerson would be compensated $750,000 for the wrongful conviction by the state.

“It’s far too little for a crime he didn’t commit but something nonetheless,” Lau said.

NC Reality Check is an N&O series holding those in power accountable and shining a light on public issues that affect the Triangle or North Carolina. Have a suggestion for a future story? Email realitycheck@newsobserver.com