Why 2018 may be the end of moderate Republicans — forever

Top Story

The breed wasn’t exactly thriving before 2018. But thanks to widespread anti-Donald Trump backlash from the very swing voters who sent them to Washington in the first place, it looks like suburban, moderate Republican Congress members may finally be facing extinction after November’s midterm elections.

Consider Mike Coffman. A former businessman and retired Army soldier and Marine Corps officer, Coffman has repeatedly found a way to win reelection in Colorado’s Sixth Congressional District — a former bastion of suburban Republicanism east of Denver that has veered leftward in recent years due to a rising immigrant population, an influx of cosmopolitan transplants and a 2012 redistricting that included Aurora within its boundaries. In 2012, voters there picked Barack Obama for president; in 2014, they chose Democrat John Hickenlooper for governor; and in 2016, they voted for Hillary Clinton by a margin of nearly 10 percentage points.

Yet Coffman — who has learned Spanish, criticized Donald Trump and been ranked the 12th most bipartisan member of the House — won every time.

This year, however, may be different. Coffman’s opponent is top Democratic recruit Jason Crow, an attorney and a former Army Ranger who advised Obama and Hickenlooper on veterans’ issues. Crow has not only matched Coffman’s fundraising dollar for dollar, raking in more than $2 million through the second quarter of 2018; he also leads the incumbent in the polls — most recently by 11 percentage points, according to Siena College and the New York Times. Even Coffman’s internal surveys show Crow ahead (albeit by a much smaller margin).

As a result, the nonpartisan prognosticators at the Cook Political Report, Inside Elections and Sabato’s Crystal Ball all say the race now “leans” or “tilts” Democratic, and the number crunchers at FiveThirtyEight give Crow an 81.4 percent chance of victory.

Meanwhile, the Congressional Leadership Fund, the super-PAC aligned with House Speaker Paul Ryan, announced late last week that it was canceling $1 million of TV airtime reserved on the candidate’s behalf — a sign that even Coffman’s supporters are losing hope.

Coffman is hardly the only Republican in that position. Attempting triage, Ryan’s super-PAC also pulled out of Rep. Mike Bishop’s district between Lansing and Detroit last week, while the National Republican Congressional Committee withdrew from Rep. Kevin Yoder’s reelection race in the Kansas City suburbs and the Pittsburgh-area contest between newly minted Democratic Rep. Conor Lamb and Republican Rep. Keith Rothfus.

A pattern is emerging here. Look at the various indices that measure bipartisanship or moderation among members of the House, and you’ll notice the same names keep popping up on the GOP side of the aisle.

A lot of them chose to retire earlier this cycle: Ileana Ros-Lehtinen of Florida; Dave Reichert of Washington state; Ed Royce of California; Charlie Dent, Ryan Costello and Patrick Meehan of Pennsylvania; and Rodney Frelinghuysen and Frank LoBiondo of New Jersey.

And now many of the rest are at risk of losing reelection in November.

The FiveThirtyEight forecasts — which account for polling, fundraising, past voting and historical trends — tell the tale. In NY-19, which covers parts of the Catskills and Hudson Valley, Democrat Antonio Delgado is running neck and neck with Republican Rep. John Faso.

In North Jersey, Democratic challenger Tom Malinowski has a slight edge (odds of victory 4 in 7) over five-term GOP incumbent Leonard Lance. In South Jersey, the odds of Democrat Andy Kim defeating Rep. Tom MacArthur are even better (2 in 3), while Republican Claudia Tenney faces the same sort of uphill battle in NY-22, east of Syracuse.

And those are just the closer contests. In the suburbs of Minneapolis, GOP Rep. Erik Paulsen has a mere 1 in 5 chance of keeping his job; his colleague Jason Lewis in Minnesota’s neighboring Second Congressional District has a 1 in 6 chance. In California, the odds of either Jeff Denham of the Central Valley or Steve Knight of the L.A. suburbs returning to Washington stand at 1 in 3. In northern Virginia, Democrat Jennifer Wexton is a 3 in 4 favorite against incumbent Republican Rep. Barbara Comstock. And in northeast Iowa — Dubuque, Cedar Rapids, Waterloo — State Rep. Abby Finkenauer, 29, is so far ahead of GOP Rep. Rod Blum in the latest polls that FiveThirtyEight gives her a 29 in 30 chance of winning.

All told, nearly half of the 40 most moderate House Republicans are either choosing to leave the chamber next year or in danger of being forced to leave.

In part, this is cyclical. Swing districts tend to elect more middle-of-the-road representatives. Midterm elections tend to break against the president’s party. So in a cycle like 2018, moderates are almost always the first to go. It happened to Democrats in 2010, when the GOP’s anti-Obama tea party wave wiped out more than half of the moderate Blue Dog coalition. And because wave elections become wave elections only when one party winds up flipping a lot of districts that typically vote for the other party, the pendulum can, theoretically, swing back; so far this year, for instance, the Blue Dogs have endorsed 20 Democratic general-election challengers, and many of them could win.

Yet there are several reasons why 2018’s potential losses among moderate, suburban Republicans could be more lasting. For years, both parties have been moving away from the middle, but the GOP’s rightward swerve has been sharper; in a party that’s less moderate overall, moderates themselves will likely have a harder time clawing their way back. Redistricting doesn’t help, either. The safer the district — whether it was drawn by Republicans in 2010 or will be redrawn by Democrats in 2020 — the less need for crossover appeal next time around.

But more than anything else, it’s Trump who may mark the point of no return for moderate Republicans. Cities have become solidly liberal; rural areas have become reliably conservative. The suburbs and exurbs are the last remaining battlegrounds. Demographically, these seats — the seats Republicans are disproportionately defending in 2018 — skew toward two types of voters: college-educated whites and Latinos. Some districts have more of the former (particularly in the Northeast and upper Midwest), some have more of the latter (particularly in the Southwest) and some have a combination (particularly in California). The problem for the GOP is that both groups have turned against Trump in historic numbers.

As long as Republicans in Congress continue to appease their base by giving the president everything he asks for — and as long as he continues to define the party in the eyes of the electorate — it’s going to be difficult for any moderate Republican to win over America’s well-educated, diversifying suburbs. The party’s ranks in Congress are likely to shift rightward as a result. They’re also likely to shrink.

Verbatim

Hot Seat

New Jersey Senate: It’s not all gloom and doom for the GOP. Despite a House map that’s turning bluer by the day, the Senate is still more likely than not to remain Republican. In fact, the party could even gain two or three seats this year, despite the national headwinds.

You’ve probably heard about some of the states Republicans could flip, such as North Dakota (where centrist Democratic incumbent Heidi Heitkamp is tied with GOP challenger Kevin Cramer) and Florida (where low-key Democratic Sen. Bill Nelson is struggling to fend off an energetic challenge by Republican Gov. Rick Scott).

You’ve probably heard less about New Jersey.

The reasons are obvious. Unlike North Dakota, New Jersey not a red state; it’s not even purple, like Florida. In 2016, Donald Trump lost there by 14 percentage points. The following year, Democrat Phil Murphy defeated Republican Lt. Gov. Kim Guadagno by the same margin. Previous GOP Gov. Chris Christie, famous for Bridgegate and the most humiliating 2016 presidential flameout, soured the already fairly progressive state on Republican rule, departing office with some of the lowest approval ratings on record (like 15 percent low). Garden State surveys now routinely show Trump underwater by 30 percentage points.

Yet perhaps it’s time to pay closer attention. On Monday, New Jersey’s Stockton University released a poll showing incumbent Democratic Sen. Bob Menendez leading his Republican challenger, Bob Hugin, 45 percent to 43 percent — a two-point gap that’s well within the poll’s margin of error.

It’s not the first survey to find a close contest. But it is the first survey to come out in the last month, which is when voters actually start tuning in to the fall campaigns.

So could Hugin actually win? On paper, he seems to have a shot. In 2015, Menendez — a senator since 2006 and a member of the House of Representatives for 13 years before that — was indicted on corruption charges stemming from his relationship with a Florida doctor who gave the senator trips on his private plane and free nights in fancy Paris hotels, allegedly in exchange for various favors. Menendez’s trial last year ended in a hung jury, freeing him to file for reelection. The doctor was convicted in a separate trial of Medicare fraud and sentenced to 17 years in prison.

Hugin has — no surprise here — made the Menendez scandal the centerpiece of his campaign, blanketing New Jersey’s ultra-expensive airwaves with months of ads about how the state’s sitting senator is a “disgrace” who “broke federal law.” Through June 30, Hugin spent $8.6 million overall; $6.3 million was devoted to media. Meanwhile, Menendez held his fire for much of the summer and barely even campaigned.

The strategy has had some sort of effect. In August, a Quinnipiac poll showed Menendez with a negative 40-47 percent approval rating and a negative 29-47 percent favorability rating; 49 percent said he had been involved in “serious wrongdoing,” compared with only 17 percent who said otherwise. Hugin’s favorability rating was slightly positive (24 percent to 20 percent), though a majority said they hadn’t heard enough about him to form an opinion. A month later, the Stockton poll essentially confirmed these findings.

By all accounts, Hugin is a real candidate. A retired Marine and the chairman and former CEO of Celgene, a global biotech company, he certainly has enough of his own money to throw around: $15.5 million through the first half of the year — nearly twice what Menendez had raised by then. He seems comfortable criticizing Trump. And apart from his attacks on Menendez, he is campaigning less on national policy than a hyperlocal list of pocketbook issues — chief among them the limit on state and local deductions that was enacted in Trump’s tax bill, which effectively raises taxes on many New Jerseyans. Sending another Republican to the Senate may be a roundabout way to correct that, but Hugin’s strategy of blaming the state’s sky-high living costs for driving away residents and railing against Trenton’s perpetual problems with pension debts could resonate in a state where even progressives are weary of the tax burden and tired of government mismanagement.

The usual caveats about relying too much on a single poll apply here as well, and the Stockton survey seems to have vastly undersampled young voters and minorities, prompting an unusual outcry from other New Jersey pollsters. For its part, Stockton says it was able to weight its results to reflect the electorate’s proper demographic breakdown. Either way, it’s worth watching the wires to see what the next few soundings look like. If they’re close as well, the question that could decide the race is whether Hugin can define himself as a preferable alternative to the less-than-ideal status quo before Menendez can define him as the opposite.

In late August, the incumbent’s first ad finally appeared on New Jersey TV. “I never forgot my roots — he has,” Menendez said on screen, referring to his opponent. “I’m fighting for equal pay and affordable health care; he’s for corporate tax breaks. I’m working to lower prescription costs; Hugin gouged cancer patients. And I’m standing up to Donald Trump. He donated hundreds of thousands to him.”

Verbatim

Best of the Rest

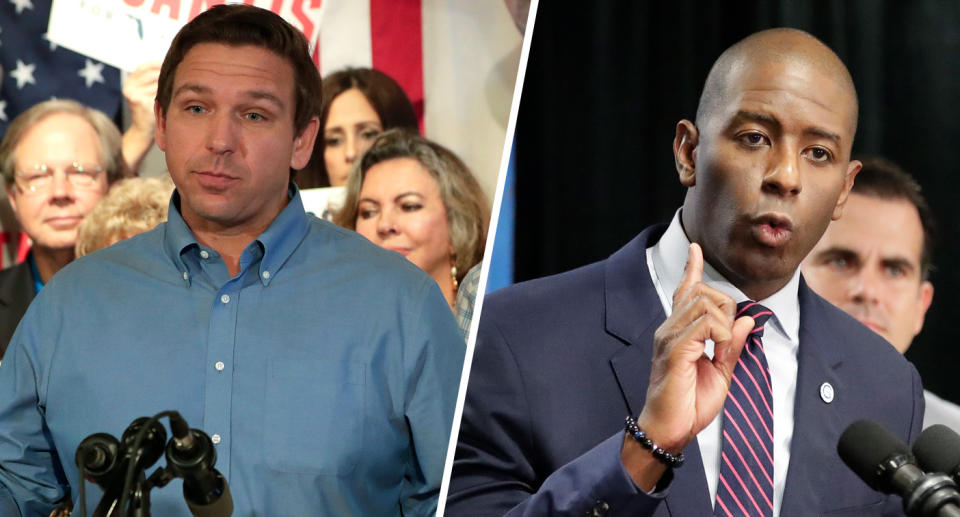

Running on race: “Monkey this up.” “Ties to terrorism.” “Big-city rapper.” No one ever said politics was pretty. But as we enter the final stretch of the fall campaign, some of the most hard-fought contests in the country are getting downright ugly.

In Florida, former Republican Rep. Ron DeSantis kicked off his general-election bid for governor the morning after securing the GOP nomination by warning Fox News viewers that his Democratic counterpart, Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum, might “monkey this up” and convince the state to “embrace a socialist agenda.” Gillum happens to be African-American. DeSantis later had to disavow a donor who wrote “F*** THE MUSLIM N*****” on Twitter in reference to Barack Obama, and clarify that he didn’t condone the alt-right hate group the Proud Boys after several members attended one of his rallies. Meanwhile, Idaho white supremacists claimed responsibility for a Florida robocall that featured a man pretending to be Gillum speaking in “the exaggerated accent of a minstrel performer” about “mud huts and unfair policing practices” while “the sounds of drums and monkeys” played in the background.

In New York’s 19th Congressional District, Republicans are not focusing on Democratic challenger Antonio Delgado’s credentials as Rhodes scholar or Harvard Law graduate. Instead, they’re taking aim at his time as a “big-city rapper.” Since mid-September, the National Republican Congressional Committee has released a pair of ads that recontextualize lyrics Delgado released a decade ago during a brief run as “A.D. the Voice” to suggest that he is misogynistic, racist and unpatriotic. Delgado “is obligated to explain what he meant by the songs he wrote, which denigrated our nation and the free enterprise system, and often glorified pornography and drug use,” his opponent, Republican incumbent John Faso, wrote in a letter to the New York Times. Delgado also happens to be African-American, and NY-19 is overwhelmingly white.

Finally, in California’s 50th Congressional District, inland from San Diego, Republican Rep. Duncan Hunter is trying to salvage his political career by saying his Democratic opponent, Ammar Campa-Najjar, is a terrorist.

“Ammar Campa-Najjar is working to infiltrate Congress,” says the voiceover in Hunter’s new attack ad. “He’s used three different names to hide his family’s ties to terrorism. His grandfather masterminded the Munich Olympic massacre. His father said they deserved to die. … ‘He is being supported by CAIR and the Muslim Brotherhood.’ ‘This is a well-orchestrated plan.’ Ammar Campa-Najjar: A risk we can’t ignore.”

“He changed his name from Ammar Yasser Najjar to Ammar Campa-Najjar so he sounds Hispanic,” Hunter added in remarks last week. “That is how hard, by the way, that the radical Muslims are trying to infiltrate the U.S. government. You had more Islamists run for office this year at the federal level than ever before in U.S. history.”

Never mind that “the Democrat on the receiving end of these attacks isn’t even Muslim” and “all the claims in the ad are false, misleading or devoid of evidence,” as the Washington Post points out. Desperate times call for desperate measures: In August, Hunter was indicted on charges of illegally using a quarter of a million dollars in campaign cash to pay for vacations, dental work, gifts and more, and a recent Democratic poll showed him tied with Campa-Najjar (though other polls found wider margins).

Likewise, Delgado leads Faso by 4.5 percentage points in the latest survey; Gillum has edged out DeSantis in every poll taken since August. Stay tuned for November’s results to find out whether racialized campaigning can still pay off in the Age of Trump — or whether the GOP has finally taken it too far.

Steal ‘Magnolia’? President Trump consumed yet another cable-news cycle with his mockery Tuesday night in Mississippi of Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, the California academic who has accused Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh of sexually assaulting her when they were teenagers in Maryland. But amid all the noise, the actual reason for Trump’s trip to the Magnolia State was overlooked: Republicans stand a real chance of losing a seat that they’ve held for the last four decades.

As Yahoo News Senior Political Correspondent Jon Ward recently reported, Democratic consultant Joe Trippi helped Doug Jones win a Senate seat in Alabama last winter, and he thinks his party might be able to pull off another surprise in the Deep South this year in Mississippi.

“The pieces are in play that make it possible,” Trippi said in a phone interview. “So far it’s played out as well as it could.”

Trippi is a media adviser to Mike Espy, the Democrat running for U.S. Senate in the Magnolia State. It’s essentially the same role Trippi played for Jones when the Democrat beat Roy Moore — the hard-right Republican battling sexual-assault accusations — in a Senate special election there last December.

Chris McDaniel, a state senator, is one of two Republicans running in a special election Nov. 6 to replace Thad Cochran, a Republican who retired last spring for health reasons. Although he doesn’t have Moore’s personal baggage, McDaniel is cut from the same cloth politically, and his persistence in the race over the opposition of more mainstream Republicans is what gives Espy supporters hope.

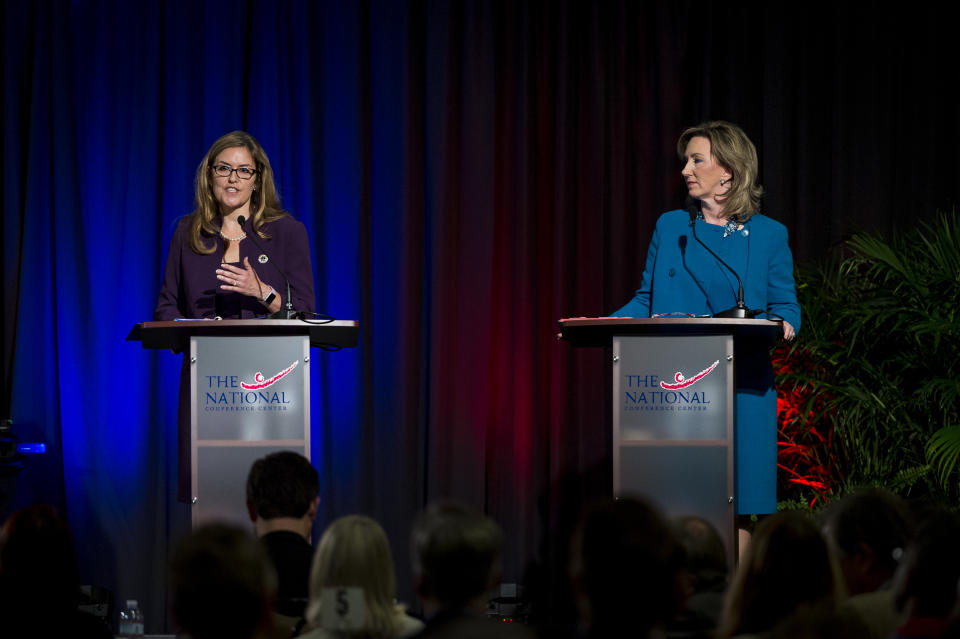

Espy’s main rivals are McDaniel, who came very close to beating Cochran in 2014 and still believes that election was stolen from him, and the incumbent, Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith, who was appointed to Cochran’s seat this year by Gov. Phil Bryant.

McDaniel has been attacking Hyde-Smith, a former state senator herself, over her past as a Democrat (she switched parties in 2010). But Trump, heeding the lesson of the Jones-Moore race, has endorsed Hyde-Smith.

The polling so far shows Hyde-Smith and Espy leading. If no candidate wins more than 50 percent of the vote on Nov. 6, then the top two go into a three-week runoff, culminating on the Tuesday after Thanksgiving.

State and national Republicans — Trump included — don’t want to take any chances on McDaniel sneaking into the runoff, which they fear he could lose. If the runoff pits Hyde-Smith against Espy, Republicans (and FiveThirtyEight) like her chances a lot better. So the GOP establishment is supporting a super-PAC that is backing Hyde-Smith by running ads against McDaniel.

Trippi said that regardless of which Republican makes the runoff, the “schism in the Republican Party” will leave supporters of the third-place candidate disaffected and disinclined to vote in the second round.

Republican strategists disagree. “If there is a pocket of voters who are pissed off after the election, they’re going to come home because Mississippi is with Trump,” said a national Republican operative who is working on the race. — Jon Ward

The man who made Beto: Rep. Beto O’Rourke is a rising Democratic star who is giving Texas Sen. Ted Cruz a run for his money in one of the most closely watched Senate races in this election cycle. And although O’Rourke rarely mentions his father during the campaign, observers of Texas politics say he has inherited much of his iconoclastic temperament and volatility from his legendary dad, reports Yahoo News National Correspondent Holly Bailey.

“There were two things you couldn’t dispute about Pat [O’Rourke]: He loved El Paso, and he had guts,” said Bill Tilney, a former El Paso mayor and foreign service officer who was in charge of the U.S. Consulate in Ciudad Juarez in the mid-1980s and who worked with O’Rourke on cross-border issues. “He didn’t have his finger in the air, trying to judge which way to go. He tried to do what he believed was right.”

But Beto O’Rourke rarely mentions his father, who died in a cycling accident in 2001. The congressman’s stump speech doesn’t focus much on his personal life story — perhaps because growing up as the son of a politician is less gripping than the tale of Cruz’s immigrant father.

But those who knew Pat see his influence all over his son’s insurgent campaign. Notwithstanding political and certain stylistic differences between father and son, Beto O’Rourke’s relentless energy, ability to connect with average people and tendency to operate more on political instinct than conventional wisdom remind many people of his dad.

After Pat’s sudden death, his friends saw a change in Beto. He took up an interest in politics, and after considering a run for county judge — his dad’s old job — he ran for City Council, taking on a well-known incumbent and mounting the same kind of aggressive ground campaign that had helped his father win. He knocked on thousands of doors, including in the barrio, going to places where politicians did not always go — the same blueprint he’s embraced in his unlikely race for Senate. The shy son of Pat O’Rourke was suddenly as charismatic as his father. — Holly Bailey

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: