20 years of Harry Potter: so what's all the fuss about?

Harry Potter turns 20 tomorrow. Not the boy wizard himself - he is 36, by our calculations - but the series of children’s books dreamed up by J K Rowling, the first of which was published on June 26, 1997. In the subsequent two decades, a spell was cast over swathes of the world’s readers, young and old alike.

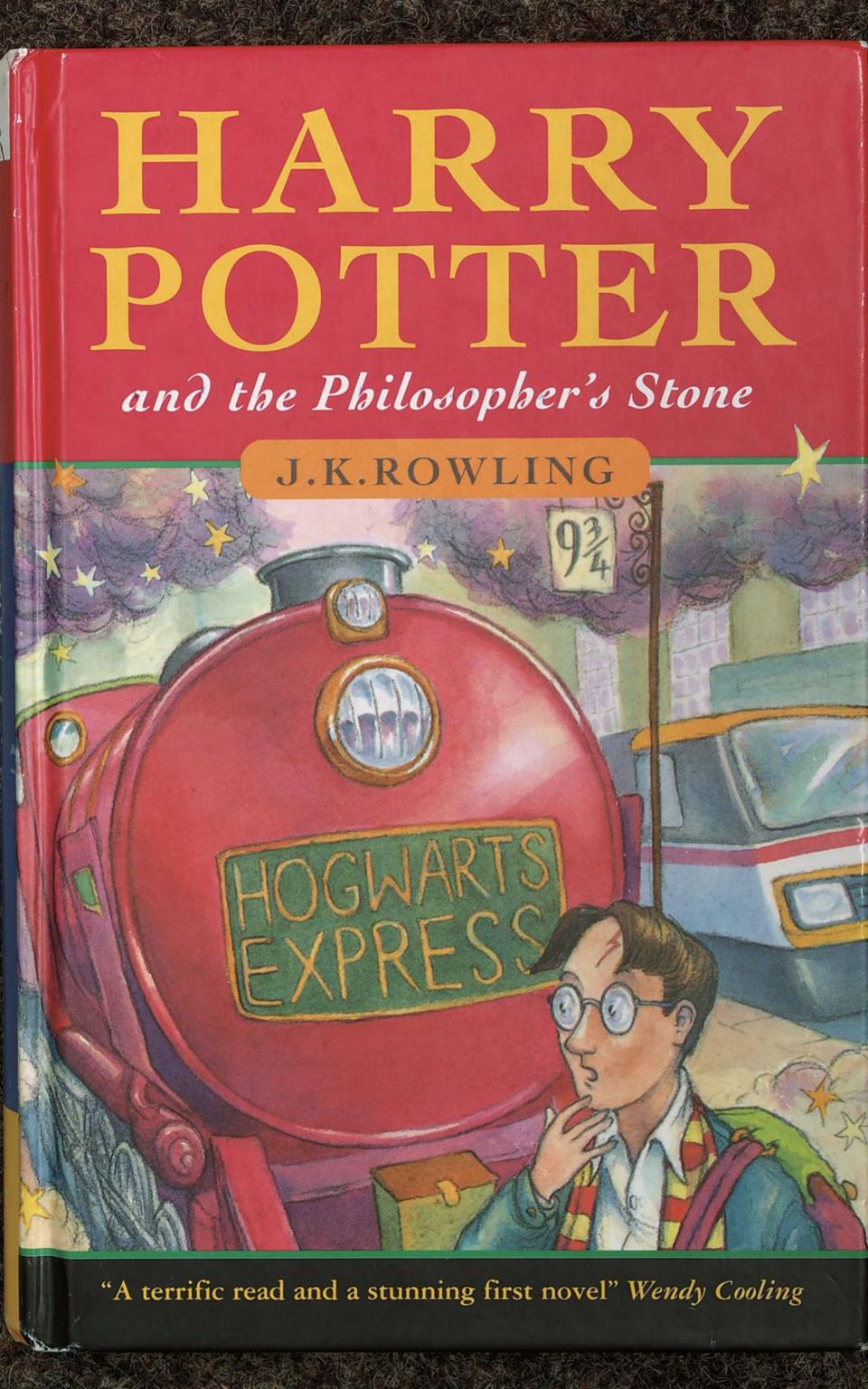

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, and the six sequels that followed it, worked the kind of magic most publishers could only dream of, selling well over 450 million copies and turning their author into a billionaire. Inspiring a devotion among fans last seen around the time of Jesus Christ, Potter became a global phenomenon.

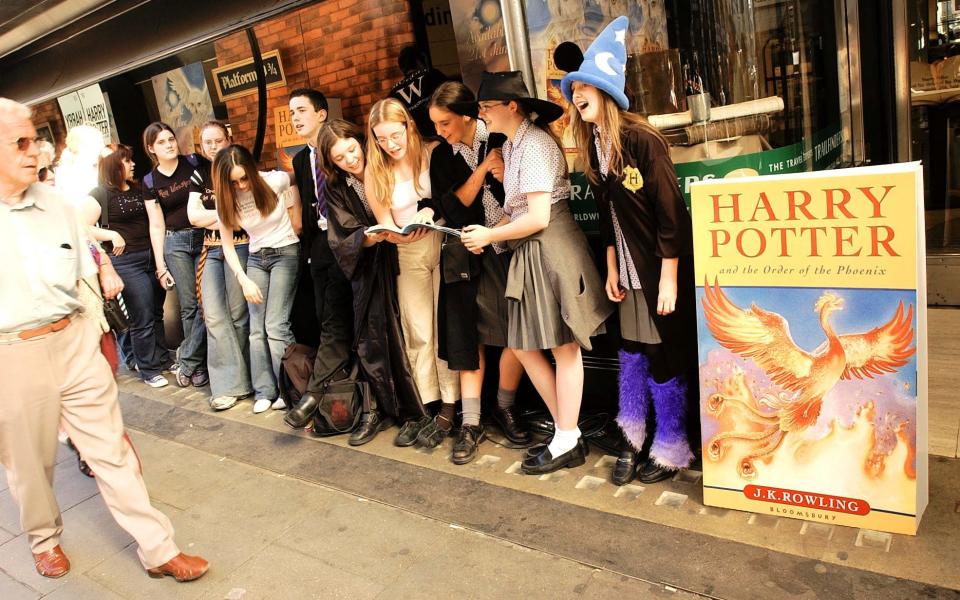

His acolytes thought nothing of joining long, night-time queues outside bookshops to await each new instalment; adult readers thought nothing of devouring the books on their commutes, coyly at first - special covers for the older fan were designed - and then flagrantly, as it became acceptable to declare yourself smitten. But how to explain all this to the uninitiated? We asked a few people to try...

A N Wilson, writer

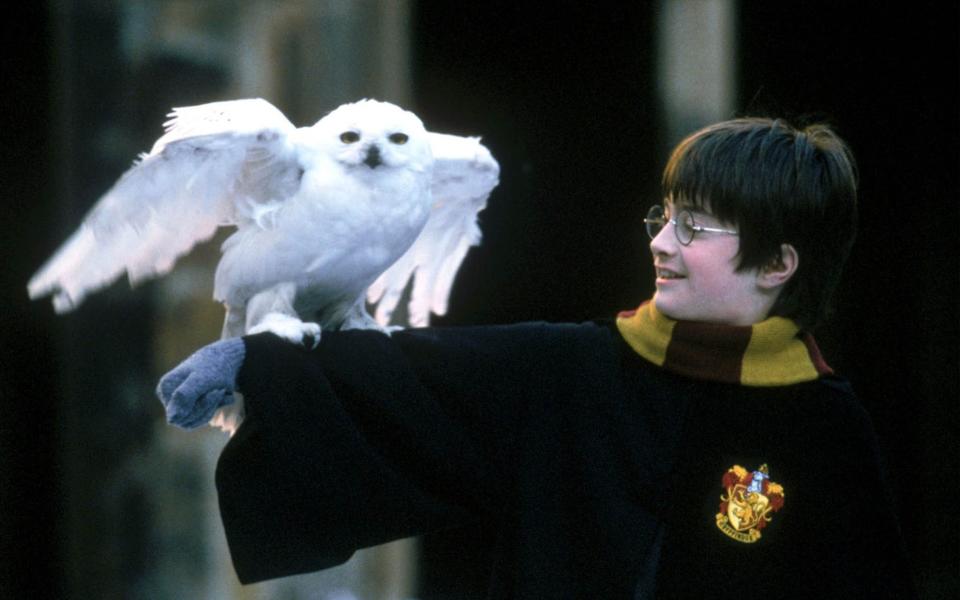

Those of us with children now in their late teens or early twenties were the lucky participators in the Harry Potter phenomenon. Ours was the first generation in years who did not have to persuade our children to read. J K Rowling did that for us. We were all drawn into the world of Hogwarts. I read all the books aloud to my daughter Georgie, and we then both re-read them many times. Rowling has, in a way, the one thing needful in a novelist: she is a compulsively addictive narrator. You long to know what happens next. She brilliantly combined two popular genres – the magic or fairy tale with the school story.

Some berated her lack of originality. True, almost all the details in the Potter tales have their origin somewhere else. The centaurs, the trolls, the three-headed Cerberus, the Quest for the missing Horcruxes… They have all been borrowed from folk-tale, or from other children’s writers. This is no more a flaw in Rowling than it is a flaw in Dante that he uses all the monsters from Ovid and Virgil to populate his medieval inferno. It is one explanation – apart from her narrative skill – for the sensation we all had, on first opening Harry Potter. It was to come home, to meet an old friend, “to arrive where we started. And know the place for the first time”.

Ian Rankin, novelist

My first immersive experience of Harry Potter came by way of the unabridged audiobooks - on cassette. They were narrated superbly by Stephen Fry. We took them with us on the long summer drive from Edinburgh to south-west France, nominally to keep our young son Jack entertained but really because we all loved the stories. I recall arriving at our destination after about 18 hours of driving and sitting in the car a further 20 minutes so we could hear how the book ended - the mark of exceptional storytelling.

Living in Edinburgh, it’s hard to escape Harry Potter fans. They make pilgrimages to the spots where J K Rowling wrote her first books and to the school(s) on which Hogwarts may have been based. But the really wonderful thing about the series is that it speaks across generations and cultures, bringing a sense of wonder to all who encounter it. Harry exists in a universe we can all visit, young and old. My son Jack is 25 now, but the lessons of the Harry Potter books live on in him - and the books (and cassettes!) still sit on his shelves.

Barry Cunningham, original publisher of Harry Potter at Bloomsbury and now publisher at Chicken House Books

Of course I didn’t know when I first read the original Harry Potter manuscript (yes, a lovely paper bundle in those days) that so many other publishers had rejected it. I just loved it at first sight. I’d worked with Roald Dahl in his glory days, so I suppose the opening chapters reminded me a little of him.

But really it was the friendship between the children that drew me in, and while I loved the owls and Hogwarts and everything, that was the real magic to me – and the humour, reminding me that laughing at danger and bullies may not make them weaker but it makes you stronger.

I couldn’t be prouder of the Harry Potter legacy: not only has it made reading cool again, it has shown that families can all enjoy great stories together. We can believe that there is a real purpose to standing up to evil. And, of course, we can find our own magic.

Richard Madeley, TV presenter

Harry Potter came along at exactly the right time for the Madeleys. Our two youngest children were at that delicate age where kids either turn left and start serious grown-up reading, or put children’s books aside and turn right into the internet and nothing else. J K Rowling’s wonderful creation ensured Jack and Chloe would develop a lasting love of reading – the old-fashioned kind, from pages you can scribble notes on, spill tomato soup on, fold down earmarks for special reference later.

The Harry Potter stories represent something else important in our family: they were the first books we all read, together. The kids loved talking about the latest Potter book and as Judy and I enjoyed them as much as they did, we had some wonderful discussions. Jack in particular relished these exchanges to the point that, when Order of the Phoenix came out and his mum and I were abroad, he spent his birthday money on two copies especially for us, so we could start reading them the moment we arrived home. They were propped on our pillows, waiting for us.

So thank you, J K. You turned a whole generation on to books, and continue to do so. On this anniversary weekend, perhaps you should get an Order of the Phoenix yourself.

Lauren Davidson, Telegraph property editor

I can chart my life through books. The tiger came to tea, then I fell through a rabbit hole, fought pirates in Neverland and played the jolliest practical jokes at Mallory Towers. But Harry Potter presented practical problems for my family in a way that Mowgli and Matilda never did. The story was new, being built around us as we devoured it, and it was for everyone, not just to be read at a certain age and then stored until the next sibling got a bit older.

In the summers, when new books were released, we pre-ordered five copies of each. There was no other option. A doting and rapid-reading father could probably be relied upon not to divulge spoilers. But if there is one person who cannot be trusted to keep a wicked secret - to go about their pestful business quietly when they know something delicious that you don’t - it’s a sibling. And if there’s anything less trustworthy than one sibling, it’s three.

Lara Prendergast, online editor of The Spectator

If you have ever wondered why young people are often so left-leaning in their politics, why they want to divide the world between tolerant progressives and wicked reactionaries, it helps to understand that the ‘Potterverse’ is the millennial universe. The Harry Potter generation sees real-life Voldemorts everywhere: Trump, Farage, Le Pen — all are compared to the Dark Lord.

Jeremy Corbyn is often compared to Dumbledore, although Rowling has been keen to point out that, in her view, they aren’t all that similar. I suspect the majority of Potter fans prefer Corbyn to Theresa May nonetheless. The Prime Minister said during the election campaign that she was a fan of the books — all politicians have to do so now — yet she refused to compare herself to any of the characters. This was not a good enough answer, so the Potterverse decided for her: May was Dolores Umbridge, a sinister, sadistic bureaucrat.

Harry’s uncle, Vernon Dursley, is the archetypal Little Englander. He lives in boring suburbia and is a narrow-minded, mean-spirited man who makes his nephew sleep in a cupboard under the stairs. No self-respecting Potter fan would want to be associated with him - or his political views. Before the referendum, Rowling confirmed what many suspected: horrible Uncle Vernon would have voted Leave.

The writer has continued to update the world she created to ensure it fits with how the Potter generation view their own political struggle. She has revealed that Dumbledore was gay and that Hogwarts would have been a “safe place” for LGBT students. The Potterverse, then, keeps developing. If Harry Potter can save the world, why can’t his fans, too?

James Daunt, founder of Daunt Books

I remember publication of The Philosopher’s Stone well: we must have sold all of five copies in the first month, which greatly cheers a small, independent bookseller. By Christmas, it was five copies a day and this, believe me, is bookseller bliss.

By the time two years had passed and The Prisoner of Azkaban was about to be published, we had sold 300. We opened the shop at midnight and made a decent fist of dressing the shop as Azkaban for The Prisoner. Two hundred people queued up.

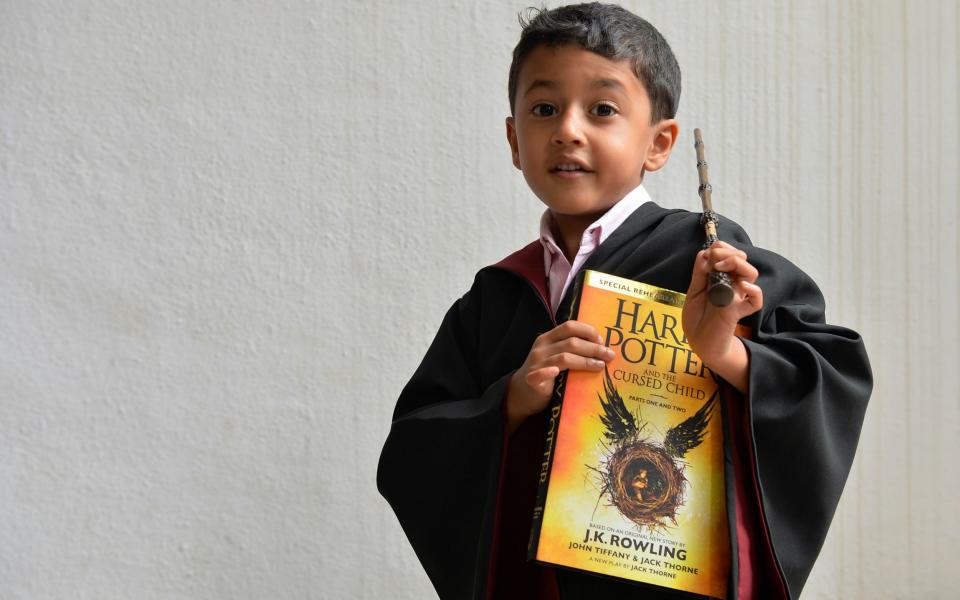

And so JK Rowling became the patron saint of booksellers. A generation of readers grew up with Harry and his world, richer, more complex and more eagerly anticipated with every volume. Independent booksellers were energised and new bookshops spread to just about every corner of the country. Most still survive, in spite of the Kindle, and we have Harry to thank for their presence in our towns. Last year with The Cursed Child we enjoyed the midnight queues and the dressing up once again. It was a much fun as ever.