2 School Districts to Testify as Congress Expands Antisemitism Inquiry

The leaders of public schools in New York City and Montgomery County, Maryland, will testify about how their districts are handling antisemitism before a congressional committee next month. It will be the first time that K-12 districts have taken center stage in the House hearings focused on how schools are responding to a wave of student protests since Hamas’ attacks against Israel on Oct. 7.

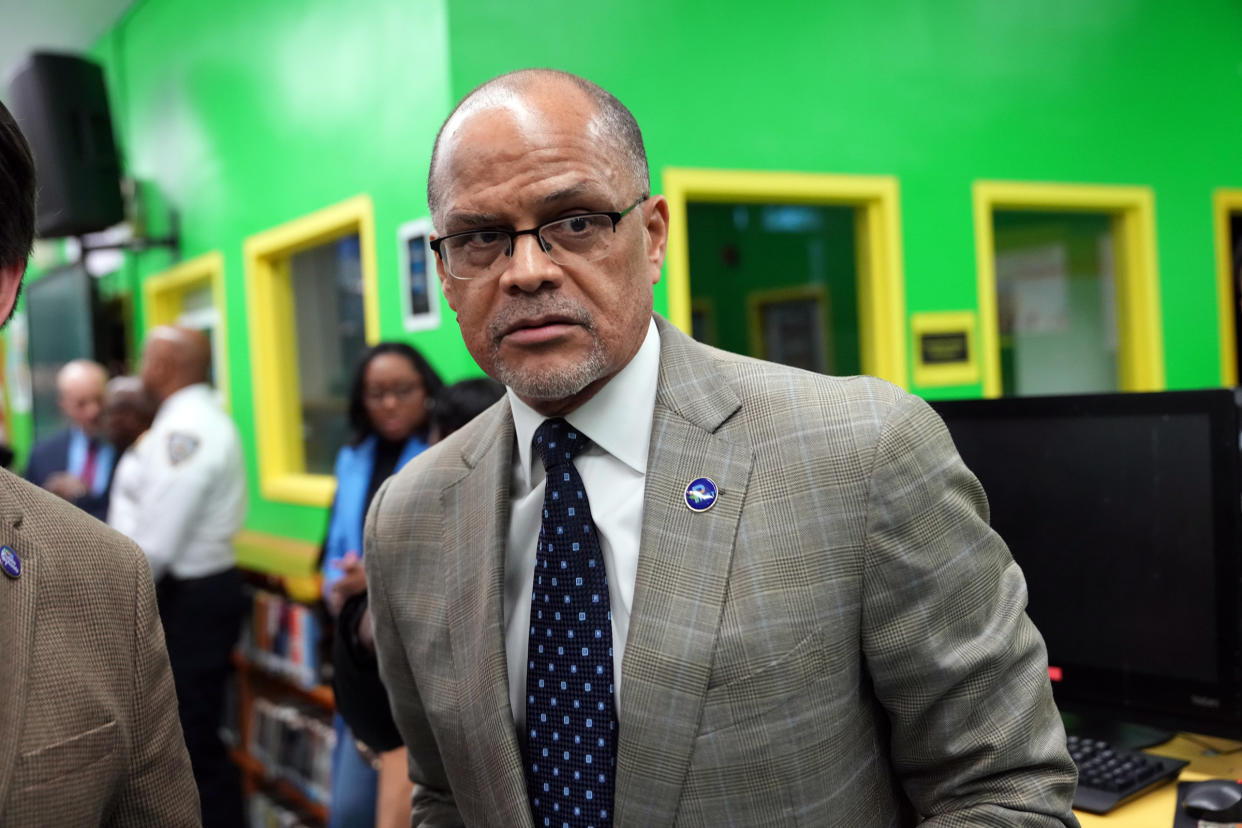

At least one other district was also invited to attend the hearing on May 8, according to New York City schools Chancellor David Banks, who will be testifying. A spokesperson for the House Committee on Education and the Workforce confirmed that the two districts were asked to attend the hearing, but did not identify others.

Earlier congressional hearings helped trigger the resignations of the presidents of Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania. Columbia University’s president is appearing before a congressional committee next week.

Sign up for The Morning newsletter from the New York Times

Now, representatives appear to be expanding their scope beyond higher education. The inquiry next month will offer a window into how the tensions on American college campuses are also stirring painful debates in public school communities.

High school students across the country have led a number of pro-Palestinian and anti-Israel demonstrations against the war in the Gaza Strip, at times drawing the ire of Jewish families.

In New York, the nation’s largest school district, the system is still grappling with the aftermath of a raucous protest at a Queens high school late last year. Hundreds of students filled the halls, and officials said some were targeting a pro-Israel teacher.

And in Montgomery County, the biggest district in Maryland, a number of local schools have struggled with antisemitic episodes, including swastika graffiti, since Oct. 7. Several teachers were also placed on administrative leave for social media posts in recent months, including one teacher who signed an email with the contested phrase, “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.”

At a press briefing Thursday, Banks said that he looked forward to discussing how the city’s school system continued “to deliver an environment of tolerance and respect.”

“We are doing our best to meet the moment,” he added.

The president of the Board of Education in Montgomery County, Karla Silvestre, will be testifying along with Banks next month. The hearing will elevate both leaders and any others who attend to one of the most high-profile stages of their tenures.

But the testimony will carry the risk of worsening tensions at home. On their campuses and beyond, the presidents of Harvard, Penn and Massachusetts Institute of Technology were excoriated when they failed to say that students who called for the genocide of Jews would be punished.

The committee could cover a similar range of issues in the K-12 hearing, including discipline policies, the handling of antisemitic episodes and student protests.

In Montgomery County, for example, Silvestre will likely be asked about the status of an investigation into the social media posts of another teacher who claimed that the Hamas attacks were a hoax.

The county had been grappling with a rise in antisemitism in schools even before Oct. 7. Those included an episode this fall at one high school, where the principal said students filmed themselves “performing an antisemitic salute.”

The district said in a statement that Silvestre was eager to share how schools were tackling antisemitism and intolerance, and creating “a safe and welcoming learning environment that supports all students.”

Banks could face questions about how students were disciplined after the demonstration in Queens. In an address at the high school, his alma mater, he called what happened “completely unacceptable.”

He may also be asked about a high school in Brooklyn, where a Jewish educator said she faced antisemitic comments and death threats from students. Banks has pushed back against the depiction of the student body, calling news coverage of the story “irresponsible” and saying it was “blown completely out of proportion.”

New York City has taken some steps to help schools and educators better handle the war. Middle and high school principals were trained last month on having tough conversations about politically charged issues.

A number of Palestinian, Arab and Muslim students and educators have also reported episodes of bias since the fall, and officials announced in January that new curriculum materials on both Islamophobia and antisemitism would be offered to schools.

Still, some local Jewish families and educators in particular have criticized the response to hateful episodes as inadequate.

Tova Plaut, a preschool instructional coordinator who has spoken out at several rallies, said at a protest before the January announcement that officials had “failed at building safe and inclusive classrooms and schools for Jewish students, families and employees.”

c.2024 The New York Times Company