10 years after Flint water crisis began, emergency manager law must change | Opinion

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

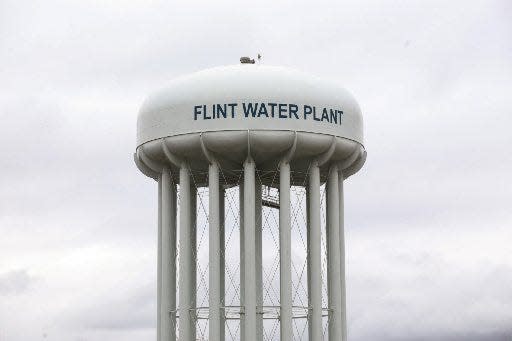

It’s hard to name just one cause of the Flint water crisis. But it is impossible to extricate the poisoning of an American city's water supply from the botched state intervention that precipitated it.

But 10 years after the water switch, the state law that enabled the appointment of four emergency managers in the struggling city remains intact.

In 2011, Flint was broke, running a $25 million deficit and struggling to provide basic services to its hundred thousand residents.

That year, Snyder appointed Flint’s first emergency manager, charged with returning the city to fiscal solvency – but without any new revenue or resources, leaving few options but to cut. With the state’s full support, Flint’s series of emergency managers signed off on a cascade of cost-saving measures that resulted in lead contamination of the city’s drinking water, exposing thousands of children to the dangerous neurotoxin.

I'm a Michigan nun. Pope Francis says PFAS contamination is a sin against God. | Opinion

For months, residents tried to get state government to pay attention, telling the city’s leaders, including the emergency manager, that their water smelled and tasted bad, that it was yellow, that it was giving their children rashes and making them sick.

No one listened. They didn’t have to. State law grants emergency managers sweeping authority, with little accountability.

In 2015, after a pediatric researcher’s work had finally proven what residents knew all along, Snyder assembled a group of experts to determine the root causes of the water crisis.

The task force's withering report meticulously chronicled the failures that led to the water crisis, and issuing a series of recommendations to ensure it could never happen again — including substantial changes to Public Act 436, the state emergency manager law that places far too much authority in the hands of one person.

Snyder stubbornly refused to advance the measures his own task force had recommended, despite having a Republican-controlled Legislature for his entire tenure as governor. Nor has Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, who has said the emergency manager law led to disaster in Flint, but that she’s not pushing its revision.

And so the remains on the books, unaltered.

Michigan cities are back on solid footing — but we're always just one economic cycle from the next recession.

That means it’s up to Whitmer and Lansing’s Democratic legislative majority clean up the mess Snyder left.

People aren't the problem

Michigan’s emergency manager law is rooted in flawed concepts: that the state exists apart from the local governments that comprise it, that cost-cutting provides a viable path out of crisis and that the way the state funds its cities is fundamentally fair.

None of that is true. Nothing makes that more plain than Flint.

The very existence of such a law is painful to some Michiganders. Under PA 436, a state-appointed emergency manager replaces local elected officials. For many who won hard-fought battles to secure the right to vote, such displacement, even if temporary, is intolerable.

But without the option of state intervention, a struggling city’s only prospects are a slow slide into unmanaged insolvency — at a cost residents may pay, literally, with their lives — or bankruptcy, bearing disastrous consequences for city services, public sector unions, residents and pensioners.

There’s also this: Residency flows two ways.

Citizens of Flint or Hamtramck or Detroit or Benton Harbor are Michiganders, entitled to state aid when the cops don’t come or the streetlights are out, and should be able to call on their state government for assistance.

In Snyder's approach, the dynamic is cast in reverse, with struggling cities and residents viewed as the problem, and state oversight as the solution.

Generations of disinvestment

Michigan ought to change the way it funds its cities.

The state is supposed to collect and dispense tax dollars to municipalities, but for the last two decades, the Legislature and governor have bolstered the state budget by shorting cities and counties billions of dollars — a poor understanding of how any system works.

The state can't buy fiscal health at the expense of its component parts, and a thoughtful Michigan would reconfigure its funding mechanisms to ensure that cities don't reach dire financial straits.

But such a broad revision of the state's funding mechanisms is not on the horizon, so Michigan cities and school districts need a better Band-Aid.

That 2016 task force report offers some sound recommendations for amendment of the law:

Amend Public Act 436, state’s emergency manager law, “to compensate for the loss of the checks and balances that are provided by representative government.”

Fundamentally change the current application of the emergency manager law, requiring the engagement of local officials, adding an ombudsman in state government to ensure that the emergency manager takes local concerns seriously, incorporate a means for the appeal of emergency manager decisions, and ensure that experts should have input on decisions that affect public health and safety.

Give emergency managers access to resources that could improve the function of a city, not simply cut costs.

That last part is particularly important. Without new revenue or resources, it’s hard to see how an emergency manager can meaningfully change a city’s financial future.

PA 436 is premised on the notion that local elected officials just haven’t tried hard enough, simply can’t make good decisions, and that an impartial outsider will make the clear-eyed choices necessary to right the fiscal ship.

Like switching a city’s water supply.

State officials from multiple administrations have expressed concern that using state funds to solve one city or school district’s fiscal crisis means others will expect the same.

They should. Michigan can't be healthy if its component parts are suffering, and yes, citizens ought to be confident that when we're in need, the state will save the day.

Ten years since the beginning of the water crisis, nine years after the story of Flint made national headlines, eight years after the report was issued, nothing about the emergency manager law has changed.

Whitmer told the Free Press last summer that she doesn't like Snyder's emergency manager law, but wasn't pushing for its amendment. Revising PA 436 will be a heavy lift for Whitmer, whose most vocal constituencies would rather see the emergency manager law repealed than altered.

But if the governor isn't prepared to reconfigure the state's municipal funding, she owes it to Michiganders to ensure there's a reasonable toolkit for cities and school districts in crisis. The 2016 task force report offers a good place to start.

Whitmer must act, before the next crisis breaks.

Submit a letter to the editor at freep.com/letters, and we may publish it in print and online.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Flint water crisis shows need to fix Michigan emergency manager law