10 unexpected ways Neanderthal DNA affects our health

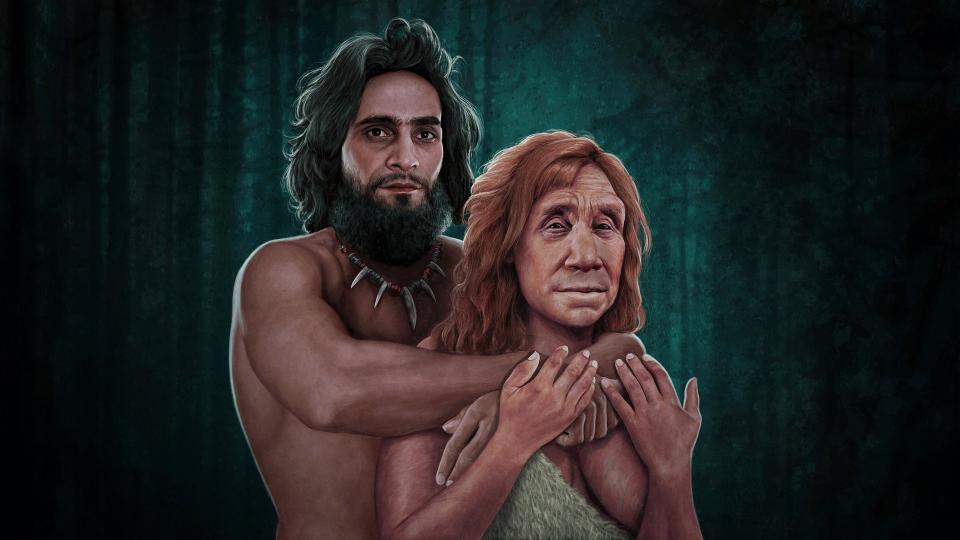

As far back as 250,000 years ago, the ancestors of most modern people in Europe and Asia left Africa and journeyed toward the colder northern terrain of Eurasia. There, they encountered our closest, now-extinct human relatives — the Neanderthals. Over thousands of years, these groups mated and exchanged DNA.

Today, we can still see the genetic legacy of these interbreeding events: approximately 2% of the genomes of people outside of Africa comes from Neanderthals.

Thanks to fossil discoveries and advances in genome-sequencing technologies, scientists have made a plethora of discoveries about the DNA we inherited from our long-dead cousins and how it may impact our health.

Here are 10 ways that Neanderthal DNA may contribute to particular diseases and physical traits in modern humans.

Related: Neanderthal woman's face brought to life in stunning reconstruction

1. Allergy risk

In 2016, scientists discovered Neanderthal genes in some modern humans that encode proteins that stimulate the immune systems' response to pathogens, and that these genes may also predispose people to allergic diseases.

Modern humans inherited gene variants from Neanderthals in a family of proteins called Toll-like receptors (TLR). TLRs are found on the surface of cells and play an important role in innate immunity — the body's first line of defense against pathogens. TLRs bind to invading microbes and stimulate the immune system to respond.

People who have Neanderthal versions of these TLR genes may be more likely to have allergic diseases, scientists found. This could be because these receptors are hypervigilant and more likely to overreact to environmental allergens.

2. Pain sensitivity

Neanderthal DNA may also make some people more sensitive to pain inflicted by sharp objects piercing the skin. A 2023 study in the journal Communications Biology found that people in Latin America who carried any of three variants in a gene called SCN9A, which is involved in pain signaling, were more sensitive to pain after being prodded with a sharp object. These variants were more commonly found in people with prevalent Native American ancestry.

"It makes much more sense that a crucial thing like pain, if it gives us a demonstrable change [in our survival chances], would be evolutionarily selected," Kaustubh Adhikari, co-senior study author and a statistical geneticist at University College London, previously told Live Science.

The findings only addressed normal sensitivity to pain, rather than chronic pain, which is when pain lasts for more than three months.

3. Type 2 diabetes risk

Mexicans and other Latin Americans may be at a higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes (T2D) thanks in part to a Neanderthal mutation in a gene called SLC16A11.

SLC16A11 is involved in fatty acid metabolism. Fatty acids likely play a major role in the development of T2D, a disease characterized by high levels of glucose, or sugar, in the blood. T2D is the most common form of diabetes and is known to disproportionately affect Hispanic and Latino people.

4. Sensitivity to sunlight and hair loss

Some Neanderthal gene variants are also associated with a greater risk of balding and sunburn in modern humans, according to a 2021 study published in the journal Nature Communications.

Scientists looked at a large repository of health and genetic data from adults in the U.K. and found that, of the 17 Neanderthal gene variants associated with balding, 15 were tied to hair loss rather than hair growth, study co-author John Capra, an evolutionary geneticist at Vanderbilt University, told Live Science.

The researchers also found that Neanderthal DNA was likely to make carriers more sensitive to sunlight. This suggests that these traits may have been beneficial to modern humans entering Eurasia, as those genes may have helped modern humans make the most out of the more limited sunlight available at higher latitudes in Eurasia, Capra said.

A separate study in 2017 similarly found that around 66% of Europeans carry a Neanderthal allele linked to a heightened risk of childhood sunburn and poor tanning ability.

5. Severe COVID-19 risk

During the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists gained new insights into how Neanderthal DNA influences human health today.

For example, a 2020 study published in the journal Nature found that Neanderthal DNA on chromosome 3, which is carried by 16% of Europeans and 50% of South Asians, is associated with an increased risk of severe illness after infection with SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19.

The picture isn't straightforward, however: In 2021, the same authors discovered that separate Neanderthal DNA on chromosome 12, carried by up to 50% of people in Eurasia and the Americas, may reduce the risk of someone requiring intensive care after COVID-19 infection by around 22%.

6. Nicotine addiction

Neanderthal gene variants may influence our ability to quit smoking. A study published in 2016 in the journal Science found that people of European ancestry who carry a Neanderthal-specific mutation in a gene called SLC6A11, are more likely to become addicted to nicotine than those who don't. SLC6A11 codes for a protein that is involved in relaying signals between different parts of the brain.

Neanderthals didn't smoke tobacco so it is possible that this gene had a completely different beneficial effect when it was selected for during evolution, Capra told Live Science in 2016.

7. Fertility

In 2020, a study published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution found that almost 1 in 3 women in Europe carry a Neanderthal gene variant that is associated with increased fertility, as well as being less likely to bleed during early pregnancy and less likely to experience miscarriages.

Specifically, these women inherited the receptor for the sex hormone progesterone from Neanderthals. In women, progesterone helps prepare the lining of the uterus for the possible implantation of a fertilized egg during reproduction. If fertilization is successful, progesterone also supports early embryonic development.

8. Depression risk

Generally, Neanderthal DNA is less commonly found in parts of our genomes that are involved in our brains, such as genes associated with cognitive function. However, in the 2016 Science study, scientists discovered Neanderthal DNA variants that are tied to mood disorders such as depression in people of European descent.

It's not clear why modern humans kept these genes, but from an evolutionary perspective, it could be tied to sunlight exposure, the authors hypothesized in their paper. In modern humans, depression risk is influenced by light levels, and Neanderthal gene variants are associated with ultraviolet protection, the authors suggested in the paper.

9. Viking disease risk

Gene variants inherited from Neanderthals may also increase the risk of developing a hand disorder called Dupuytren's disease or contracture.

Dupuytren's disease occurs when the tissue under the skin in the palm of the hand thickens and becomes less flexible. This can cause one or more fingers to contract and become frozen in a bent position. The disease is sometimes nicknamed "Viking disease" because it is very common in Northern European countries where the Vikings settled.

In a 2023 study of people who were primarily of European descent, scientists discovered 61 gene variants linked to a greater risk of Dupuytren's disease, three of which were of Neanderthal origin. These included the EPDR1 gene on chromosome 7 that is involved in muscle contractility.

10. Autoimmune risk

Neanderthal DNA lives in us

'More Neanderthal than human': How your health may depend on DNA from our long-lost ancestors

Read more:

—What's the difference between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens?

—The mystery of the disappearing Neanderthal Y chromosome

Immune system-related genes inherited from Neanderthals may also contribute to autoimmune diseases, in which the body's immune system mistakenly attacks its own cells.

A 2014 study published in the journal Nature found that certain Neanderthal gene variants in modern humans are associated with the risk of developing two chronic disorders: lupus, which affects many parts of the body including the joints, skin and kidneys; and Crohn's disease, an inflammatory bowel disease.

The researchers found a variant tied to lupus in around 10% of Europeans and less than 1% of East Asians, while approximately 26% of Europeans and 8% of East Asians carried another variant linked to Crohn's disease.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!