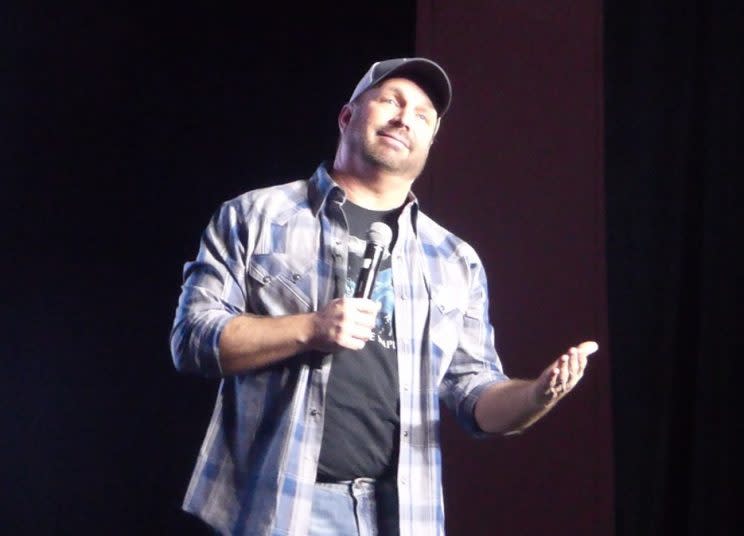

From Streaming Music to Labels to Concerts: Garth Brooks Does It His Way

Garth Brooks is probably never going to cover “My Way,” but the sentiment, if not the song, belongs to him more than anybody else in music in the 21st century. After virtually all the other superstar holdouts have finally given into the world of digital singles multiple streaming services, Brooks explained his continued resistance to those popularly accepted models in a talk before hundreds of radio programmers and DJs in Nashville Thursday.

In a highly entertaining one-hour talkfest, he also regaled the Country Radio Seminar attendees with similes about the sensual pleasures to which live performance is akin… and dropped a title and concept for his next album (hint: it one-ups Double Live).

“Concerts are like sex, actually,” he said. “Think about that. Because the whole time, you’re working to get an invitation back,” Brooks elaborated, to gales of laughter. Later in the Q&A, he expanded on that thought in more childlike terms. “I apologize every night for turning into a 5-year-old kid. It’s what the music does…I wish I could explain it, because it goes against all logic, because I’m closer to 60 now than 50, so it shouldn’t work like this. But… forgive me if you’ve heard this. If your job was eating ice cream for a living and your boss said ‘You’re gonna have to pull a double shift today’… I don’t know if you were listening to the ‘Concerts are like sex’ part, but it’s fantastic.”

And soon, all that sex-and-candy-like concert love will be re-commemorated on record.

“Double Live was released almost 20 years ago, and it’s certified at 21 million,” Brooks pointed out, speaking in a ballroom at Nashville’s Omni Hotel. He said he’d been given data showing that 48 percent of the attendees who’ve caught his post-retirement tour over the last three years were 10 years old or younger — some not even born — when he last toured in the 1990s. “Now you’ve got a whole half of an arena that you’re wondering: How do they know this stuff?… They know it from Double Live. They don’t know ‘Thunder Rolled’ and ‘Friends in Low Places’ without the third verse [which didn’t appear on the studio versions], and they are waiting on it… I think it’s time to put [Double Live] to bed, and at the end of this tour — of course it has to be better, so Triple Live will probably be coming out.” He half-apologized for the bigger and better conceit implicit in the title: “That’s just what we do — sorry.”

But will you be able to stream it? Only if you subscribe to one of Amazon’s music services. Late last year, Brooks signed a deal with Amazon to stream his music exclusively, and also to sponsor his tour. He remains not so big a fan of the other services, which he’s never allowed to get hold of his music, even after extensive talks over the years. Brooks told the CRS crowd that “we’re trying to stay out of the mud today, trying to keep it positive. Talking about the music business, especially over the last 15 years, can get kind of depressing, and you want talks to be light and airy, right?” But he did get into the intricacies of his mercurial interactions in the music business. And he spoke freely about why his 2014 deal with Sony Nashville came to an end after just one album (Man Against Machine), followed by going indie with his own label, Pearl, for last year’s follow-up (Gunslinger).

“I’ve had great relationships and not great relationships” with major labels, he said. “You’re always fighting for the music. Labels fight for the music, but they’re publicly owned companies, so they have other agendas … When we came back out of retirement, things had changed a ton in the music business…. We signed with Sony coming out — very sweet; great company — but what Sony found out very quickly is the same thing we found out very quickly. We own our own masters. We don’t stream. And we don’t do digital downloads. So it was tough. Why don’t you do digital downloading? Apple [is] the digital downloader, and Apple has a set of rules and if you didn’t play by those rules you didn’t get in the game. Well, to a guy like me that was here before Apple got here… What if I don’t want to sell just singles? What if you want to do album-only?… And why are you telling me what I’m going to price it at? I’ll price it at what I want to price it at, and if the people think it’s too high, they won’t get it. That’s a fair system. But if you don’t play by their rules, you don’t do it. So when it came to Sony, they realized no digital downloads, no streaming, and no YouTube — there’s the big one right there. [Between] those three things, you realize, holy cow, I’m no good to a label.”

Brooks didn’t mention his own largely forgotten attempt at a rival to iTunes, Ghost Tunes. But he made it clear he was aware of the need for a partner as he ramped up his own Pearl Records, post-Sony. “We had had wonderful talks with Spotify, and we had had honest conversations with iTunes,” he said, carefully choosing his adjectives “Daniel [Ek] at Spotify — sweet kid. Talked to him. His parents were street musicians. ITunes, they’ve got their views on music… We’re just in the wild west right now with digital. So what I didn’t care for with streaming is, I feel like us as the industry, we’re standing on this rock of music. But what we’re doing is we’re eroding it very fast. We’re just taking money” without thinking about all the implications, he said. “We say, ‘You want to come in the vault and just steal whatever you want? Go for it. As long as you pay the record labels or the copyright owners’… I didn’t want a streaming company that did that, that says, ‘Look, [don’t] ask any questions; I just pay you this, you let me play this.’ I wanted a streaming company that says, ‘How does streaming help you as an artist? How does it help the songwriters? How does it help music overall?’ Nobody had ever asked me that. Why hasn’t anybody asked me that? So I loved these guys [at Amazon]. They asked the right questions. Nice people. And,” he added, “they wrote a good check.”

As he often does, Brooks positioned himself as a champion of songwriters, above all. “How a songwriter lives in this town is you get what were called album cuts back then. You get album cuts on a Randy Travis or George Strait record. That pays your rent for six more months, seven months maybe… Then all of a sudden somebody calls you and says you’ve got a single. If it weren’t for those album cuts, that songwriter would have not stayed in this town long enough to feed himself and his family. That’s how the system worked. So when you talk about iTunes, it’s like, hey guys, if I want to [allow] album-only [downloads], why shouldn’t I?… I’m sure you guys have heard the stats. It’s a scary statistic. Since 2000, Nashville’s lost over 80 percent of its songwriters. Eighty percent. If something’s not good for the songwriters, people, it’s not good for the music, trust me.”

He’s also molding the touring business in his own image. “Other artists will put on-sales on six months or a year out, and it’s all for business reasons which I totally get. For us, we like to take a city and grab it, and just not let it go, like ‘Oh my god, I’ve got to hold this thing’… So six weeks before the show we’re gonna announce. Five weeks before the show, we’re gonna put the tickets on sale, and hopefully it’s just gonna boil. And then our job when we come into the city is to burn that thing down.”

Keeping ticket prices low and audience interaction high is his m.o. for the most successful sustained touring in popular music. His populism is infectious, even in a speech: “Going to a concert might be the biggest pain in the ass there’s ever been,” he said. “Getting tickets, good luck. Getting honest tickets, good luck. Nobody ever goes by themselves, [so] double that. Bring your kids, and double that; if not, babysitters. You want to take your spouse to dinner on the way to the concert…. Try a beer at the concert. They’re as much as the T-shirts are. In Boston, the parking was more than the price of the concert. It’s a pain in the ass to go to these things. And yet they show up, man. They show up in the back frickin’ rows and they’re as excited as the people in the front.

“One of the first concerts I went to was Queen. My girlfriend Tammy had bought tickets. We couldn’t afford ‘em, but she bought ‘em and surprised me. We stood on the 13th row, stood on our chairs, and all I wanted was Freddy Mercury to look at me for three seconds so I could go ‘Thank you man, thank you. I know I shouldn’t be making my decisions by listening to your music, but I am.’ So as you now play, all you’re looking for is that three seconds to each person out there to say, thank you.”

Did he get that moment with Mercury, an audience member asked? “No, I did not get that three seconds,” he admitted. It will be up to others to wonder whether Brooks is still trying to work out that near-miss in Freudian proportions by getting so promiscuous with his gaze at his own shows. “If you want to give everybody in the crowd three seconds, at 17,000 people, you’re not gonna get to all of them,” he conceded. “But from that show there, I realized the kind of entertainer I wanted to be. And I think he was one of those guys that if he had known I wanted those three seconds, he would have given it to me. So that’s my job as an entertainer, to find you for that time. And if you look like Miss Yearwood, I’m gonna come back to you two or three times.”

Brooks is so much about setting records that it’s easy to crow exclusively about the stats: No. 1 solo artist in history, with 149 million albums sold; five-time CMA Entertainer of the Year winner, including holding the current belt. But he also alluded to the fact that his enduring massiveness on the touring circuit has not translated to an unbroken string of radio hits since he came out of retirement. His current single, “Baby, Let’s Lay Down and Dance,” just peaked at No. 15 on Billboard’s Country Airplay chart, and that was his most successful radio record since he hit No. 1 with the comeback single “More Than a Memory” in 2007. It’s hard for anyone over 40 to catch a break with the increasingly youth-focused format right now, fellow legends like George Strait included. In front of the crowd that matters, he wasn’t above admitting he still wants it.

“There’s a song on the Christmas record [from 2016] that shouldn’t be just a Christmas record, called ‘What I’m Thankful For’,” he said. “This song, when it’s over, people just sit there for minutes. I’d like for you to think about this: If it was 1994, or 1992, and we released that song today, it would be ‘Unanswered Prayers.’ It’s all about timing. So I know Lesly [Simon, Pearl Records’ general manager] is going to [makes the motion for poop] herself, because she never, ever thought I’d say this. I’m gonna ask you: Treat Garth Brooks like it’s 1992. Play the hell out of it. See what happens.”

He offered a rosy prediction for radio, regardless, presumably, of whether he resumes his status as a constant chart-topper. It’s human nature, he said, to desire the curating only radio offers.

“Because I’m in this room,” Brooks told the radio programmers, “it’s going to be accepted very well, but it’s not to s*** you, it’s exactly what I think is going to happen… People, we can stream all day. But when you get tired of streaming, when you have to request every frickin’ song that’s coming up, I would much rather sit back and have it sent to me, and if I don’t like it…” He made the motion for punching the dial. “Terrestrial radio is here forever. If that makes you in 20 years go ‘Oh my god, what a square guy, he couldn’t see the future’… I’ll put money on it. If I had to invest money, I’d put it on terrestrial radio over streaming. You guys might go [to a] subscription [model], but it’s still about not knowing what the next song is, but liking it when it gets there… How many songs have you hated the first time that you heard ‘em, and that became the song that you played at your wedding? That’s how we are as people: sometimes we need to hear things two or three, seven, 10 times before we get familiar with it. You’re not gonna get that with [songs on demand]. You’re gonna give it 15 seconds — next. You’ve just screwed yourself. But terrestrial radio doesn’t do that. So I think that’s why it’s still gonna be ‘Play it for me, and surprise me.’ Why am I getting up in the morning if that isn’t happening?”