What to Stream: ‘Moonlight’ Director Barry Jenkins’s Feature Debut ‘Medicine for Melancholy’

Before the Oscar-winning Moonlight was a glint in his eye, Barry Jenkins entered the film industry as part of the mumblecore generation with his 2008 debut Medicine for Melancholy. Currently streaming on Netflix and available for download in iTunes, Medicine showcases many of the attributes that made Moonlight such a stunner, including a remarkable sense of place — the streets of San Francisco, as opposed to Jenkins’s hometown of Miami — and a subtle eye toward the nuances of two people looking to connect.

Related: Oscars 2017: Why the Moonlight Best Picture Win Is a Really Big Deal

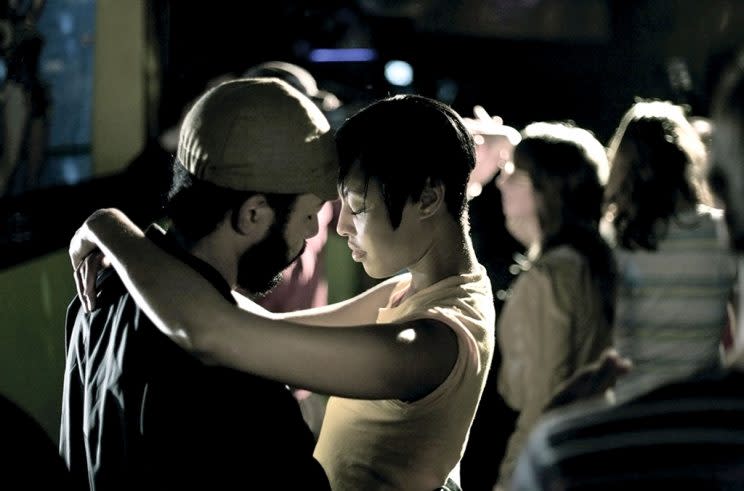

The film opens with Micah (Wyatt Cenac, who started his four-year stint at The Daily Show as a correspondent in the summer of 2008) and Jo’ (Tracey Heggins) waking up in bed together following a drunken one-night stand and proceeding to do the awkward morning-after dance before going their separate ways. Michah then tracks her down under the auspices of returning her wallet, but really because there’s something about her that fascinates him — in much the same way that Moonlight‘s central character, Chiron, is intensely drawn to his schoolmate Kevin.

Where Jenkins’s sophomore feature spans decades, Medicine for Melancholy takes place in the compressed timespan of one day, as Jo’ and Micah walk, talk, and occasionally cycle around San Francisco. Shooting on digital video, Jenkins captures a muted, locals-only version of the city. That aesthetic choice and the unaffected performances are probably why Medicine for Melancholy was tagged with the “mumblecore” label when the film premiered at the 2008 South by Southwest film festival.

Watch the trailer:

South by Southwest, by the way, is also where “mumblecore” happens to have been coined in 2005 as a means to describe a wave of scruffy independent films that prioritized naturalistic dialogue over heightened style. It quickly became the catchall term to characterize such then-emerging (and now well-established) directors as Mark and Jay Duplass (The Puffy Chair), Joe Swanberg (Hannah Takes the Stairs), Lynn Shelton (We Go Way Back) and Lena Dunham (Tiny Furniture).

Speaking to Filmmaker magazine in 2008, Jenkins emphasized that Melancholy wasn’t made in the mumblecore mold. “I purposely did not look at any of the so-called mumblecore films before we made the movie,” he said, adding that he was inspired by the economical way that directors like Swanberg produced their no-budget films, rather than their specific style.

And the film he made bears that out; there’s a lyricism to the specific sequences — most notably a bit of afternoon nookie back at Micah’s place — that you don’t see in, say, The Puffy Chair. Jenkins’s characters also directly address racial and economic concerns that rarely crossed the minds of the unkempt white hipsters at the center of most mumblecore movies. (Not for nothing, but those questions were also rarely addressed by Jesse and Céline, the couple at the center of Richard Linklater’s influential Before Sunrise trilogy — movies that Jenkins cited as personal favorites in that same Filmmaker interview.) Eight years may separate Medicine for Melancholy and Moonlight, but the vision behind both movies is timeless.

Read more: