We Ranked All 23 Ron Howard Movies, from Worst to First

Ron Howard began his career as a child actor on The Andy Griffith Show, and then hit it even bigger as a teen star in American Graffiti and TV’s Happy Days. Yet it’s behind the camera that the has made his most indelible mark. Over the past three decades, Howard’s been behind a string of beloved critical and commercial hits that span a wide range to winning ends, from biopics (A Beautiful Mind) to sentimental fantasies (Splash, Cocoon) to grown-up comedies (Parenthood) to rugged Westerns (The Missing) and out-of-this-world adventures (Apollo 13). Howard has carved out a niche as one of mainstream American cinema’s foremost purveyors of touching stories about flawed individuals striving for prizes just out of reach — be they love, loved ones, sanity, eternal life, ancient mysteries, or the heavens themselves.

Throughout his career, the 61-year-old Howard has stretched himself by working in a variety of genres, as if, like one of his protagonists — including Chris Hemsworth’s whale-hunting sailor in this December’s In the Heart of the Sea — he too is in search of ever-more-exciting new challenges. Where that Moby Dick-origin story will fit into Howard’s canon remains unknown, but in anticipation of its awards-season release, we seek to bring order to the director’s filmography by delineating the masterpieces from the missteps — an endeavor that’s resulted in this, our definitive ranking of his 23 directorial features. (All photos by Everett Collection.)

23) How the Grinch Stole Christmas (2000)

The biggest box-office hit of Howard’s career (a whopping $260 million domestic haul), this adaptation of Dr. Seuss’s beloved holiday book is the blockbuster that everyone saw and virtually nobody liked. Drowning in whimsical Seussian production decor that suffocates any and all life in the proceedings, and led by a Jim Carrey performance that’s full of belligerent mugging, Howard’s Grinch is an assault on one’s eyes and ears. By pitching its action as so doggedly cartoonish, the film undercuts the Grinch’s real nastiness and, consequently, sabotages the poignancy of his eventual transformation. Even worse, it misguidedly expands upon its source material, replete with flashbacks to the villain’s traumatic childhood that reveal the oh-so-empathy-inducing reasons for the Grinch’s anti-Christmas behavior. Grinch ultimately drowns in such saccharine sentimentality — and is hampered even further by garish costumes, candy-colored set designs, and hideous makeup effects for everyone’s exaggerated upturned-snout noses.

22) Made in America (2013)

One can hardly tell that Howard is the man behind the camera for Made in America, a documentary about the 2012 Philadelphia music festival that was organized by Jay Z and sponsored by Budweiser. A personality-free affair that plays like a TV special expanded to feature length, this nonfiction effort is a conventional concert trifle through and through, moving back and forth between performance footage and interviews with the rock, soul, hip-hop, and pop stars appearing at the event (including Pearl Jam, the Hives, Run-DMC, and Janelle Monáe). Alas, there’s no real dynamism to the various clips of musicians doing their thing to adoring crowds — all of which are shot with technical skill but very little in the way of flair. It’s a depressingly disposable work-for-hire effort from Howard.

21) The Dilemma (2011)

The Dilemma’s release was plagued by controversy, courtesy of a line in its trailer that many — including GLADD — deemed homophobic, and which was eventually cut from subsequent promotions. That contentious advance buzz turned out to be more noteworthy than the film itself, a shaky blend of character-based drama and slapstick humor that never seems to know where it wants to go, who it wants its characters to be, or what it’s trying to say about anything. The titular dilemma in question involves Vince Vaughn’s auto-design businessman, who spies the wife of his best friend and partner (Kevin James) kissing another man, and then struggles to decide whether or not to reveal this infidelity. It’s hardly the sort of inventive quandary around which to base an entire film, and Howard never manages to generate much comedic energy from the various shenanigans that ensue from his premise. Spotty and lethargic, it plays like a first draft rushed into production.

20) Far and Away (1992)

Far and Away is best remembered for being the project on which Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman fell in love, and that’s with good reason — an overblown melodrama that misses no opportunity to indulge in contrivances, Far is a leaden slog. That’s a shame, considering that it was beautifully shot in 70 mm. Nonetheless, no amount of widescreen visual splendor can make up for the tired absurdities peddled by its story, about a working-class Irishman (Cruise) who, along with a proper young lass (Kidman), flees to America, and after much bickering during their trip out West, falls in love with the woman. From time spent in a brothel to Cruise’s character making ends meet through bare-knuckle boxing, the film functions as a series of increasingly nonsensical developments. Howard’s cinematography aims to imbue this material with epic romantic import, but such efforts are undermined by a script (and performances) that prove to be painfully simplistic.

19) The Da Vinci Code (2006)

Dan Brown’s best-selling novel The Da Vinci Code is an inert piece of historical mystery fiction, and thus it’s little surprise that Howard’s adaptation (which made $218 million) is similarly stilted and preposterous in equal measure. Saddled with a story that vacillates between faux-erudite conversations about feminine religious and artistic symbolism and frantic car chases meant to provide some energy to the otherwise dialogue-heavy narrative, Howard dully tries to gussy things up with lots of cinematographic fancifulness. His camera pans, tracks, soars, and swoops with reckless abandon in a vain attempt to energize symbologist Robert Langdon’s (Tom Hanks) quest to beat a murder rap and find the Holy Grail. While Sir Ian McKellen delivers an animated supporting turn as one of many figures involved in the central conspiracy, Hanks’s performance is mainly defined by his goofy long hair, and his wholesale lack of romantic chemistry with Audrey Tautou’s cryptologist. Code is a tailspin of dull anagram puzzles and dreary religious philosophizing.

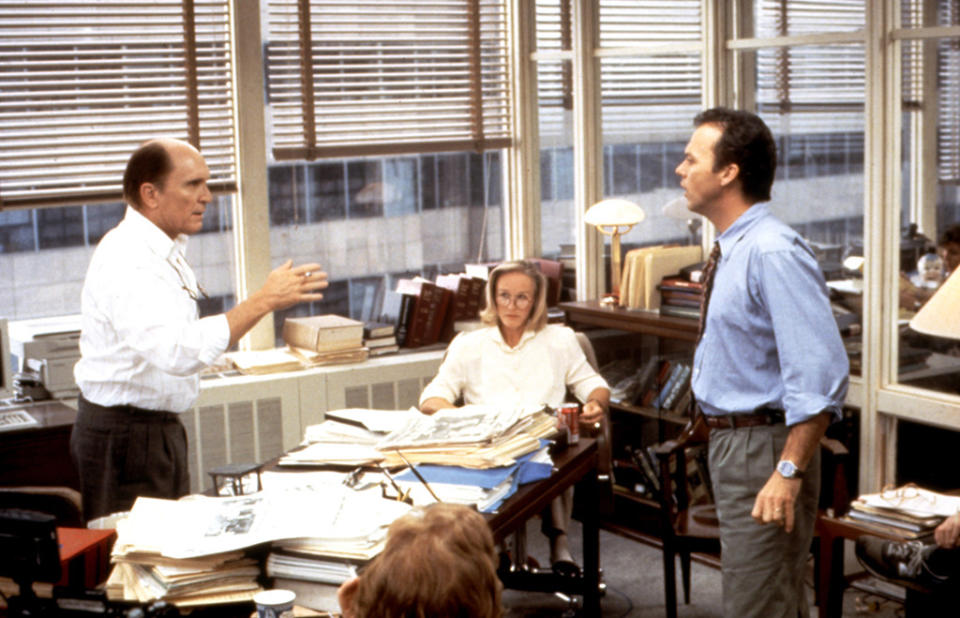

Howard on the set of ‘Gung Ho’ with Michael Keaton.

18) Gung Ho (1986)

With Japanese automakers making enormous inroads in America, 1986’s Gung Ho seemed like a potentially timely clash-of-cultures comedy. Instead, Howard’s film plays like the lamest of foreigners-are-different disasters, its tone almost as ungainly as its plotting is ridiculous. As its one saving grace, Michael Keaton — reuniting with Howard after 1982’s far superior Night Shift — brings so much manic energy to the proceedings that, even when his auto-plant bigwig is making an ass of himself in front of Japanese businessmen, he’s a likably off-kilter protagonist. However, the story, about Keaton’s attempts to revitalize his Pennsylvania auto factory by partnering with a Japanese car corporation, results in dismal one-note humor in which the Japanese are presented as efficient robots and Americans are portrayed as fun-loving brothers-in-arms. It’s a labor-related clunker full of excruciating stereotypes that are now as outdated as the cars its characters aim to produce.

17) Willow (1988)

A fantasy epic born from a story by George Lucas (which he apparently first dreamed up before Star Wars), Willow proved an uncomfortable fit for its director. Handling his fantastical swords-and-sorcery action in such a dull, straightforward manner that he fails to come up with a single truly memorable image or set piece, Howard’s stewardship drags the film down into bland, ordinary territory — a significant problem, given that its tale is merely a whimsical hodgepodge of countless science-fiction and fantasy predecessors. Mixing and matching elements from Mad Max, The Lord of the Rings, Peter Pan, Snow White, and others, Willow plays like a larger-than-life photocopy of a photocopy. Moreover, Warwick Davis’s pint-sized Willow is a rather ho-hum hero who never infuses the material with the sort of rip-roaring attitude that might enliven its plot about a motley crew’s mission to protect a chosen-one baby from an evil sorceress. Val Kilmer’s dashing-rogue routine remains the best thing about Willow, even if he eventually comes across as merely a secondhand Han Solo stuck in a lame wannabe-Star Wars saga.

16) Angels & Demons (2009)

A sequel to 2006’s The Da Vinci Code (albeit one that’s based on a Dan Brown novel that was originally a prequel), Howard’s Angels & Demons reunited him with favorite leading man Hanks, here sleepily reprising his role as sleuthing symbologist Robert Langdon. That it features a less absurd plot than its predecessor is about the nicest thing one can say about this dreary adventure, in which Langdon is again tasked with solving all sorts of intricate history-based puzzles — feats he accomplishes with such ease that it destroys any measure of suspense. As Langdon attempts to prevent a secret cabal known as the Illuminati from blowing up the metropolis using an antimatter bomb, Howard stages numerous lame car chases around the Vatican City, as well as turgid debates about science and religion. Like his star, Howard’s direction is woefully sluggish, and the result is a film that barely seems motivated to even pretend that its mysteries and action are of any significance at all.

15) Grand Theft Auto (1977)

Howard made this, his directorial debut, when he was just 23 years old, and it exudes the sort of unpretentious slam-bang energy of his acting work in Roger Corman’s Eat My Dust (made the previous year). Little more than a litany of car chases that invariably conclude with vehicles crashing and burning in extravagant ways, Grand Theft Auto isn’t about storytelling but about automotive destruction, and in that respect, it’s a mildly successful entry in that disreputable B-grade subgenre. Unfortunately, its demolition-derby set pieces are barely inventive or exciting enough to sustain even its brief 84-minute runtime — a problem exacerbated by the fact that its tale, about two young lovers (Howard and Nancy Morgan) fleeing her disapproving parents to Vegas, where they plan to get married, is just a flimsy pretext for getting its protagonists out on the open road. As far as disposable novelty indies from the era go, it’s perfectly passable cartoon-pulp entertainment, but it barely hints at Howard’s future A-list directorial potential.

14) Cinderella Man (2005)

Howard’s second pairing with Russell Crowe (after their Oscar-feted A Beautiful Mind) is this egregiously syrupy fairy tale about James J. Braddock, a down-on-his-luck boxer who, while enduring considerable hardship during the Great Depression, got a second chance at triumph, and the title, in the mid-1930s. No musty trope goes untouched by Howard in this fanciful ode to American can-do perseverance, as the director drenches his based-on-real-events story in gauzily lit sepia-toned visuals that give the film a cornball archival-movie quality. More frustrating, Howard excessively seeks to amplify his material’s poignancy through overblown imagery — lone figures in spotlights, menacing villains in close-up — that are so bludgeoningly over-the-top, they decimate any chance at legitimate emotional engagement with this redemption tale. The centerpiece pugilistic bouts are staged with concussive electricity, and Crowe does his best to counter the movie’s hagiographic tendencies by lacing Braddock’s nobility with anger and frustration. Still, the film’s mawkishness is so insistent that it renders everything and everyone phony — including, most notably, the cutie-pie performance of Renée Zellweger as Braddock’s wife.

13) Frost/Nixon (2008)

With screenwriter Peter Morgan (The Queen) adapting his own overpraised play of the same name, Frost/Nixon finds Howard floundering in his attempt to marry his big-budget style to a small-scale story about playboy TV interviewer David Frost’s memorable 1977 interviews with shamed U.S. president Richard Nixon. Casting its tale in a simplistic David-vs.-Goliath mold, Howard’s film is perhaps the most painfully unsubtle work of his career, full of ill-advised sweeping camerawork that doesn’t mesh with his intimate drama, as well as countless scenes in which his characters bluntly articulate the very ideas and developments already addressed by the action at hand. As such, the superficial Frost and disgraced Nixon’s battle, in which they both seek the respectability denied to them by their peers, is a classic example of telling instead of showing — and then telling some more, just in case anyone missed it the first five times. Frank Langella’s soul-deep performance as Tricky Dick is so magnetic that it occasionally counteracts the material’s gracelessness, though there’s ultimately no saving the film from its own wrongheaded desire to hold its audience’s hands along every twist and turn of its underdog-makes-good tale.

12) Backdraft (1991)

There are some nifty special effects in Backdraft involving fire, which plumes, explodes, and rages with terrifying ferocity throughout this saga of Chicago firemen on the trail of a serial arsonist. In its centerpiece sequences, Howard’s direction boasts a fleet, fierce dexterity that’s only been sporadically present in his work, and it does much to enliven what’s otherwise little more than a rote procedural marked by one clichéd narrative strand after another. From the rivalry between two firefighter brothers (Kurt Russell and William Baldwin) to the investigation by those men alongside a fire inspector (Robert De Niro) into a series of incendiary crimes, the film’s story is built upon a rickety foundation of clichés that are handled with formulaic competence by the all-star cast (also including the late, great J.T. Walsh). Worse, the identity of the villain is so painfully telegraphed from the story’s outset that any modicum of suspense is negated and puts the focus more squarely on tedious sibling- and romance-related minidramas. If ultimately too hokey to resonate as a compelling story, it nonetheless delivers enough adrenalized action to make it a passable multistrand thriller.

11) Edtv (1999)

Howard’s Edtv was sabotaged, in large part, by timing — specifically, by the fact that it was released less than a year after the similar, critically hailed The Truman Show. Time, however, has been kind to Howard’s 1999 satire, about a goofy everyman named Ed (Matthew McConaughey) who’s selected to headline a show about his every waking moment. Persistently followed around by cameras, Ed’s life becomes an unholy mess, full of romances that wax and wane according to the participants’ celebrity (and popularity), and family revelations that — foreshadowing our present Kardashian-saturated TV landscape — are tailor-made for prime time. The film’s portrait of people willingly exploiting themselves for media attention is hardly a groundbreaking conceit, but Edtv’s everything-recorded-in-real-time plot still resonates forcefully today and is bolstered by underrated comedic turns by McConaughey and the supporting cast, including Woody Harrelson and Jenna Elfman. Moreover, it captures, with wry cynicism, both our national appetite for building up, and then tearing down, those in the spotlight.

Russell Crowe and Howard on the set of ‘A Beautiful Mind’

10) A Beautiful Mind (2001)

The complicated life, and mental state, of Nobel Prize-winning mathematician John Nash is given the treacly triumph-of-the-will Hollywood treatment in A Beautiful Mind, the film that nabbed Ron Howard a Best Directing Oscar even though, at every turn, his work exposes his mushiest impulses. With his camera spinning around his protagonist to suggest his tumultuous headspace, and with CG effects making plain the way in which his fractured psyche teases out solutions to complex academic problems, Howard’s direction is heavy on gloss, light on substance. That’s also true of Akiva Goldsman’s script, which — with almost no adherence to factual accuracy — recounts Nash’s studies at Princeton, professorship at M.I.T., marriage, and collaboration with the government to break supposed Communist codes. Crowe’s deserving Oscar-winning performance captures the tangled madness of this brilliant but troubled man, and Jennifer Connelly is immensely moving as his loyal, long-suffering wife. But Howard persists on pulling at his audience’s heartstrings with a fairy-tale version of Nash’s victory over his problems, resulting in an occasionally affecting film that’s like a feel-good fantasy version of a thorny real life.

9) Night Shift (1982)

After following up his 1977 directorial debut Grand Theft Auto with a trio of TV movies, Howard returned to feature filmmaking with this rollicking 1982 comedy about two late-night morgue workers who set up a prostitution ring at their place of employment. Helping keep such a ludicrous premise alive are the film’s two standout lead performances by Henry Winkler and Michael Keaton, the latter in his first starring role, as clowns who decide to facilitate the sex-for-money business of Shelley Long’s lady of the night,. With Winkler underplaying his character’s nobility and Keaton letting loose with hyper energy as a wacko with one outlandish idea after another (the best: feeding mayonnaise to tuna, in order to save a step on their path to becoming human food), Night Shift has comedic energy to burn, and Howard handles his rambunctious material with suitable liveliness. While a sentimental second half neuters some of the movie’s gonzo vigorousness, Keaton’s gangbusters turn is so infectiously off-the-wall that, even 33 years later, it remains one of the director’s most purely funny offerings.

8) The Missing (2003)

An overt riff on John Ford’s The Searchers and the many antiheroes-rescuing-a-young-kidnapped-girl-from-savages movies that followed it (including Taxi Driver and Hardcore), Howard’s 2003 Western is never quite convincing on a narrative level but boasts a raw ugliness that makes it a welcome detour from his usual comfort zone. A frontier tale of rescue, the film (based on Thomas Eidson’s 2005 novel The Last Ride) concerns the efforts of a single mother (Cate Blanchett) to reclaim her snatched daughter from the clutches of Indians with the help of her long-absent father (Tommy Lee Jones), who’s spent years living among, and learning from, the American natives. While that setup leads to action sequences that primarily resonate as forced and false (especially when Blanchett’s plot-device younger daughter winds up in danger), and even though the Indians’ mystical “witch” leader borders on an offensive stereotype, the director’s portrait of life on the range has a cold, chilling nastiness that’s bracing.

7) Cocoon (1985)

Arguably the most Spielbergian of Howard’s many directorial efforts, 1985’s Cocoon charts the sweetly uplifting adventure undertaken by a group of senior citizens after they take a swim in their retirement community’s pool, and — thanks to the alien cocoons nestled beneath the water — find themselves magically rejuvenated. Howard’s depiction of the ravages of old age, and the fantasy of turning back the hands of time, is characterized by soft-focus lighting, gentle comedy, and considerable sentimentality. Although one wishes his sillier instincts trumped his sappier ones, there’s charming amusement to be had from the sight of Don Ameche (in an Oscar-winning supporting role) using his newfound vitality to break dance. Howard can’t quite stick his landing, which involves a mixture of fuzzy science fiction and even fuzzier religiosity, but he wisely keeps his material’s emphasis not on his younger characters (including Steve Guttenberg) but his over-70 players, including Ameche and Maureen Stapleton, who bring genuine pathos to this portrait of the simultaneously scary and exciting process of navigating life’s home stretch.

6) Rush (2013)

Again teaming with screenwriter Peter Morgan (Frost/Nixon) for a real-life story of two opposing rivals facing off in the spotlight, Howard delivers a conventional but electric high-speed sports saga with Rush. Fixating on the 1976 Formula One racing season, Howard’s breathlessly paced film charts the competition between hunky English racer James Hunt (Thor’s Chris Hemsworth) and calculating Austrian pro Niki Lauda (Daniel Brühl). Their clash of personalities is the skeleton upon which Howard fleshes out a captivating snapshot of the era’s mixture of glamorousness and danger, the latter always hanging over his characters’ heads. At each other’s throats both on and off the track, the two protagonists engage in a duel that, narratively speaking, affords few surprises — especially if you know how things turned out for both of them. Yet Howard’s direction is consistently energetic, with his camera attaching itself to steering wheels and squealing tires, and peering out of racers’ visors, to convey the heady ecstasy of this most perilous of professions. It’s some of Howard’s most purely exhilarating filmmaking.

5) Splash (1984)

There’s nothing particularly revolutionary about Splash, Ron Howard’s 1984 hit about a young boy who encounters a mermaid and, years later as an adult (Tom Hanks), falls in love with that very same mythical creature (Daryl Hannah), who’s transformed into a human in order to find him in NYC. And there’s no escaping that Howard’s direction is, at this early stage of his career, still beholden to stiff sitcom rhythms. Still, there’s much to cherish about this old-school romantic fable, from Hanks’s endearing cheeriness to Hannah’s fish-out-of-water innocence to John Candy’s womanizing comedic relief as Hanks’s lothario brother. The film offers frequent hijinks via a subplot involving a scientist (Eugene Levy) intent on proving that Madison is a tailed nymph, and it affords a humorously canny portrait of modern materialism as the means by which people define themselves — a notion made plain by the mermaid’s decision to adopt the name Madison (after the Avenue), and by the fact that her first word is “Bloomingdale’s.” It’s a throwback that rests on the shoulders of its three leads, and on Howard’s deft balance of saccharine amour and slapsticky craziness.

4) Ransom (1996)

Based on a 1956 Glen Ford film, Ransom operates on the surface as a traditional kidnapping thriller about a successful businessman (Mel Gibson) who’s forced to make difficult choices to recover his son after the boy is snatched by Gary Sinise’s crooked cop. Howard handles these familiar genre proceedings with rugged tautness, keeping the pace brisk and the energy high. Yet far more interesting about his 1996 hit is the way in which it revels in the uglier aspects of its nominal hero and the moral dilemmas he faces. A man under investigation for bribery, Gibson’s protagonist is targeted specifically because of his shadiness (that is, he’s apt to pay his problems away), and the actor seems simultaneously most dubious — and interesting — after deciding not to give in to the criminals’ demands, but instead to find them so he can mete out some violent justice. As such, Ransom is not only vigorous and violent but also somewhat dark and twisted as well, and it’s to Howard’s credit that he doesn’t shy away from the nastiness of his tale — on the contrary, he allows it to flourish.

3) The Paper (1994)

Few films have ever captured the rush of daily journalism like The Paper, a breakneck film that covers a 24-hour period in the life of many reporters at a fictional New York City newspaper. Led by a superbly obsessive Michael Keaton as an editor willing to do anything — harm his reputation, squander a better job opportunity, abandon his pregnant wife — in order to nail down a big story, Howard’s superior 1994 film gets both the passion and mania of writers’ committing their every fiber to their latest assignment. Humming with fanatical life, Howard’s film concentrates on Keaton and his comrades’ investigation into the arrest of two African-American teenagers for the murder of out-of-town businessmen — apprehensions that Keaton believes are mistakes, and the result of a police coverup. With a cast that also includes Robert Duvall, Glenn Close, Marisa Tomei, and Randy Quaid, the film boasts a raft of nuanced characters whose various foibles, hang-ups, and traits are convincingly messy, and it has a fast-and-furious desperation that’s in tune with newspaper reporting’s break-it-before-your-rivals-do spirit. No matter its overly feel-good ending, The Paper is one of the finest films ever made about the media.

2) Apollo 13 (1995)

Resembling something like a John Ford film set in space, Apollo 13 delivers a stirring portrait of heroism through its expert retelling of the failed 1970 Apollo 13 lunar mission. Howard delivers both superlative white-knuckle excitement and inspirational drama with this historical thriller, in which Tom Hanks’s astronaut is tasked with getting himself, his craft, and his crew back to Earth in one piece after their trip to the moon goes awry. Hanks’s excellent good-guy performance is the axis around which the rest of the equally strong supporting turns orbit (the stellar cast includes Kevin Bacon, Bill Paxton, Kathleen Quinlan, Gary Sinise, and Ed Harris). Howard skillfully interweaves all of the characters’ strands into his main tale, all while fondly re-creating the period with exacting, nostalgic precision. Evoking both the wonder and horror of interplanetary travel, as well as the courage and sacrifice required to embark upon such journeys, Apollo 13’s realism extends from its rocket-related science to its three-dimensional characterizations. Helmed keenly by Howard, who always keeps his eye less on the stars than on his quietly valiant protagonists, it’s an ode to American daring and resourcefulness that stands as one of the decade’s most purely rousing hits.

1) Parenthood (1989)

Few modern American comedies have so accurately tapped into the multifaceted dynamics of becoming a parent — and having to deal with your elders — as Parenthood, a film that, 26 years after its initial release, stands as Howard’s ultimate triumph. Rich in character detail and wise about the imperfections of grown-ups and kids alike, it flip-flops between a number of interlocking narratives concerning the various members of a four-generation clan, with Howard seamlessly nailing the thrill of poop jokes and the terror of watching one’s progeny go down an ill-advised road. Led by Steve Martin, Mary Steenburgen, Jason Robards, Dianne Wiest, Tom Hulce, Martha Plimpton, Rick Moranis, and a young Keanu Reeves, the film nimbly locates the way in which day-to-day family life can be so tough, complicated, and nerve-racking as to border on the absurd. Parenthood recognizes the simultaneously funny and fearsome task of trying to live up to parents’ expectations while also setting an example for future generations — a push-pull that’s grounded in the script’s astute recognition of the fact that all adults are also kids. More than in any of his other works, Howard here exhibits a gift for getting at universal human truths with a sharp visual touch, and via an incisive blend of the humorous and the heartfelt.

Watch the trailer for ‘In the Heart of the Sea’ below: