Special Report: How China's weapon snatchers are penetrating U.S. defenses

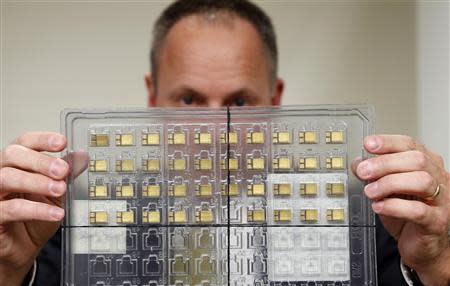

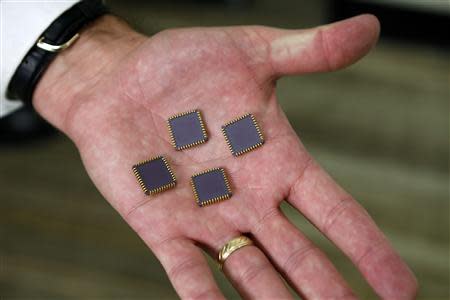

By John Shiffman and Duff Wilson OAKLAND, California (Reuters) - Agents from Homeland Security sneaked into a tiny office in Oakland's Chinatown before sunrise on December 4, 2011. They tread carefully, quickly snapping digital pictures so they could put everything back in place. They didn't want Philip Chaohui He, the businessman who rented the space, to learn they had been there. Seven months had passed since they'd launched an undercover operation against a suspected Chinese arms-trafficking network - one of scores operating in support of Beijing's ambitious military expansion into outer space. The agents had allowed a Colorado manufacturer to ship He a type of technology that China covets but cannot replicate: radiation-hardened microchips. Known as rad-chips, the dime-sized devices are critical for operating satellites, for guiding ballistic missiles, and for protecting military hardware from nuclear and solar radiation. It was a gamble. This was a chance to take down an entire Chinese smuggling ring. But if He succeeded in trafficking the rad-chips to China, the devices might someday be turned against U.S. sailors, soldiers or pilots, deployed on satellites providing the battlefield eyes and ears for the People's Liberation Army. Entering He's office at 2:30 that December morning, the agents looked inside the FedEx boxes. The microchips were gone. The supervisor on the case, Greg Slavens, recoiled. "There are a bunch of rad-chips headed to China," Slavens recalls thinking, "and I'm responsible.'" In the past 20 years, the United States has spent trillions of dollars to create and deploy the world's best military technology. It also has enacted laws and regulations aimed at keeping that technology away from potential adversaries such as Iran, North Korea and the nation that poses perhaps the most significant long-term threat to U.S. military supremacy, China. China's efforts to obtain U.S. technology have tracked its accelerated defense buildup. The Chinese military budget - second only to America's - has soared to close to $200 billion. President Xi Jinping is championing a renaissance aimed at China's asserting its dominance in the region and beyond. In recent weeks, Beijing has declared control over air space in the contested East China Sea and launched China's first rover mission to the moon. IMMEDIATE THREAT As China rises to challenge the United States as a power in the Pacific, American officials say Beijing is penetrating the U.S. defense industry in ways that not only compromise weapons systems but also enable it to secure some of the best and most dangerous technology. A classified Pentagon advisory-board report this year, for instance, asserted that Chinese hackers had gained access to plans for two dozen U.S. weapons systems, according to the Washington Post. But the smuggling of technology such as radiation-hardened microchips out of America may present a more immediate challenge to the U.S. military, Reuters has found. If China hacks into a sensitive blueprint, years might pass before a weapon can be manufactured. Ready-made components and weapons systems can be - and are - used immediately. Beijing says its efforts to modernize its military are above-board. "China has mainly relied on itself for research and development and manufacturing," the Chinese defense ministry said in a statement to Reuters. "China always complies with relevant laws and cooperation agreements and protects intellectual property rights." How often the Chinese succeed at acquiring U.S.-made weaponry or components is unclear. U.S. government officials say they don't know, in part because the problem is too widespread and difficult to track. By its very definition, black market smuggling is hard to monitor and quantify. Quite often, sensitive U.S. technology is legally shipped to friendly nations and then immediately and illegally reshipped to China. China also presents a special challenge: It is both the largest destination for legally exported American-made goods outside North America and the most or second-most frequent destination for smuggled U.S. technology. A 2010 classified Pentagon assessment showed a spike in legal shipments to China of "dual-use" technology - products that have civilian and military purposes, a person involved in the study said. The technology products the Chinese military seeks tend to be miniaturized, and thus aren't easily identifiable to U.S. border agents - unlike drugs, for example. And trafficking in these goods isn't technically illegal until someone tries to export them. "When you think about how many legitimate transactions go to a place like China, it makes it very difficult to track," said Craig Healy, a senior Homeland Security official who directs the U.S. export enforcement center. Officially published U.S. estimates of how frequently American arms technology gets smuggled are incomplete. By one Pentagon calculation, suspicious queries to U.S. defense manufacturers by entities linked to China increased 88 percent from 2011 to 2012. The government won't disclose the number of cases that underlie that percentage. U.S. defense and intelligence officials said that although they closely monitor the Chinese buildup, they believe China remains at least a decade behind America. "They still have a long way to go," said one senior U.S. defense official. Reuters analyzed court records from 280 arms-smuggling cases brought by the U.S. government from October 1, 2005 to October 1, 2013. Reporters also interviewed two dozen counter-proliferation agents and reviewed hundreds of internal Federal Bureau of Investigation, Homeland Security and Commerce Department documents. The number of counter-proliferation arrests related to all countries quadrupled from 54 to 226 from 2010 to 2012, internal law enforcement records show. Since 2008, the number of China-related space-technology investigations - like the undercover case against the Oakland man - has increased approximately 75 percent, U.S. law enforcement sources said. Since late 2012, federal agents say they have begun nearly 80 space-and-satellite-related investigations. "I think we're getting better at this, but this stuff is rampant," said FBI assistant director for counter-intelligence Robert Anderson Jr. Anderson was referring to cases involving all potentially hostile nations, not just China. "The more you dig in these cases," he said, "the more potential investigations you find." Said a U.S. diplomat based in China: "I think we do a good job on the cases that we learn about, but it's really just a finger in the dike." A MAN NAMED "HOPE" U.S. counter-proliferation agents say the 2011 Oakland sting is typical of dozens launched recently against people trying to acquire space and missile technology for China. It also demonstrates the difficulty in dismantling smuggling networks, even when a target appears patently suspicious from the outset. The Oakland investigation began in spring 2011. The manufacturer, Aeroflex of Colorado Springs, Colorado, received an email from a man who called himself Philip Hope of Oakland. The man wanted to buy two kinds of rad-chips - 112 of one type and 200 of the other. The total cost: $549,654. The initial email triggered suspicion. People and companies who buy these kinds of rad-chips are usually well-established, repeat customers - more multinational corporation than mom & pop. Aeroflex salesmen had never heard of "Philip Hope" or his company, "Sierra Electronic Instruments." Most suspicious of all, just days after placing the order, Hope sent Aeroflex a certified check for the full amount, $549,654. That was rare. Buyers were expected to make a deposit, but nobody paid up front. The suspicious Aeroflex employees contacted Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), a division of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, which keeps a special counter-proliferation office in the space technology hub of Colorado Springs. Based on quick record checks, the HSI agents drew a portrait of "Philip Hope." The man was a Chinese immigrant and legal permanent resident, Philip Chaohui He, an engineer for the state of California assigned to a Bay Bridge renovation project. Sierra Electronic Instruments was a start-up run from the one-room office in Chinatown. The HSI agents concluded that He was buying the rad-chips on behalf of someone else. Someone rich. Someone who couldn't legally acquire them. Probably someone in China - likely the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corp, a state-run entity that operates nearly all of China's military and civilian space projects. China Aerospace officials did not respond to requests for comment. An official at a Shanghai subsidiary said he was unaware of the He purchases. The rad-chips He ordered from Aeroflex are not the most powerful on the market, and could not operate a sophisticated military satellite on their own. But experts say they have few uses other than as one of the many components of a sophisticated satellite. "You wouldn't spend that kind of money on those microchips unless you intended to use them in much bigger satellites," said Alvar Saenz-Otero, associate director of the Space Systems Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. "They fit the design of a satellite that you'd want to stay in space for a reasonably long time, and therefore are likely small parts of a bigger satellite." Despite the concerns about where and how the components might be used, He's order of 312 rad-chips violated no law. These chips may be legally sold domestically, and to foreign buyers who obtain a State Department license. They may not be exported outside the United States to certain nations, including China. He had the chips sent to his office address in Oakland, making the deal legal. If He tried to take them abroad, he'd be breaking the law. THE AGENTS' DILEMMA The agents faced the key question that comes in almost every counter-proliferation case: Could they lure the suspect into a sting? If so, would it be worth the trouble? Undercover operations are time-consuming, expensive and risky. If agents dangled rad-chips in front of the suspect and he got away, the components would probably end up on Chinese satellites. If they delivered the chips and watched him closely, he might lead them to a network traceable to Beijing. The agents in the case faced another complication: At the time, Aeroflex - the very manufacturer enlisted to help with the sting - was itself under civil investigation for sending rad-chips to China. Although that investigation was still under way, Aeroflex had already admitted that it sent more than 14,500 rad-chips to China between 2003 and 2008. Aeroflex exported more than half of those chips even after U.S. officials had directed it to stop doing so. The company declined to comment. But documents show two mitigating factors - Aeroflex voluntarily disclosed the transgressions, and it blamed them in part on misreading complex and sometimes competing Commerce Department and State Department regulations. Even so, State Department regulators would ultimately conclude: "The exports directly supported Chinese satellites and military aircraft, and caused harm to U.S. national security." Thus, if the HSI agents wanted to attempt a sting against the man in Oakland, they would have to trust a company that had admitted aiding a potential enemy on a much larger scale. On July 28, 2011, a federal agent posing as a Federal Express driver arrived at He's office building in Oakland. The agent handed He's wife a package containing the first order, 112 rad-chips. She leaned it against a wall. The undercover agent wore a hidden camera that recorded the office's 10-by-12-foot interior. The place had sleeping bags and mattresses on the floor. There was no satellite research equipment. The agent departed, but not before leaving a tiny surveillance device. For the next five weeks, the device indicated that the box didn't move. Agents also put a camera outside the office door, placed a keystroke-logger on He's computer and monitored his movements based on his cell phone location. They placed his name on an automated watch list at airports and border crossings. But they didn't have the manpower to tail him. He slipped out of the country on September 6, taking a flight to San Diego and driving across the border at Tijuana. The agents received an automated security alert only the following day, September 7. They also learned that He was booked on a flight from Tijuana to Shanghai that evening. It was too late. They'd missed him. Was China about to receive 112 military-grade microchips for its space program? There was no way to know for sure. The agents had two options: Drop the case, or send He the second batch of chips and try to catch him exporting those. ANOTHER SURPRISE On October 6, an undercover agent helped FedEx deliver the second shipment, 200 radiation-hardened chips. Once again, the agents waited and watched. When two months passed with no indication that He had moved the microchips, Slavens sought the sneak-and-peak warrant. The late night search, on December 4, turned up empty boxes. Slavens then sought a warrant for He's home and renewed the airport and border look-outs. On the morning of December 10 - before the agents could complete the search warrants - the smuggler surprised them again. An agent noticed He's cell phone on the move, far south of Oakland, heading toward Los Angeles - presumably to Tijuana again, and then on to China. Slavens scrambled Homeland Security Investigations agents near Los Angeles. The L.A. agents followed the cell-tracker to a Best Western hotel south of the city. In the early evening, they located He's Honda sedan in the hotel parking lot. They confirmed that He had checked in, and they settled in for surveillance. At about 8:45 a.m. on December 11, 2011, He left his hotel room with an unidentified traveling companion and pulled the Honda onto Interstate 110, driving south. Tijuana was two hours away. The HSI agents planned to stop him at the Mexico border. But after just 3 miles, He pulled into the Port of Long Beach. Then, he used a Transportation Safety Administration pass - a badge he carried for his Bay Bridge repair assignment - to swiftly get through port security. The agents caught up as the Honda drew near a red and white cargo ship flying a Chinese flag. Stenciled on the mast were the letters ZPMC. This was the same company with the Bay Bridge repair contract to which He had been assigned by the California transit agency. A coincidence? The agents couldn't be sure. (ZPMC did not respond to requests from Reuters for comment.) HSI agents stopped He and his friend as they approached the ship captain. An agent opened the trunk. Stuffed inside a tub of Similac infant formula, authorities found 200 radiation-hardened Aeroflex microchips. The agents say the captain told them that he expected to receive "household goods" and other consumer purchases from He for delivery to friends in China. The captain and He's driving companion were permitted to leave. He was handcuffed. Under questioning, He told the agents that he'd started his Oakland business at the behest of a Shanghai electronics broker who promised to reward him with a condominium in China for his assistance. THE MISSING CHIPS In August, more than five years after Aeroflex admitted wrongdoing, the State Department announced an $8 million fine for the company's 2003 to 2008 satellite microchip shipments to China. If Aeroflex completes remedial measures, such as training employees to follow rules the company already should have been following, half of the fine will be suspended. In September, He pleaded guilty in federal court in Colorado. He is scheduled to be sentenced Wednesday. Federal guidelines call for a sentence of 46 to 57 months. In a court filing, his lawyer disputed the government's assertion that He knew the rad-chips were destined for use by the Chinese government. Assistant federal defender Robert Pepin said He believed they would be used for commercial mining satellites. Pepin said He deserves a sentence of no more than 24 months, noting that He faces certain deportation when his sentence concludes, and potential separation from his children, who are U.S.-born citizens. "The life he knew and enjoyed is destroyed," Pepin said. Despite the scope of the investigation, no one else was charged. The others in the suspected network - the ship captain, the Shanghai broker, the traveling partner and another Oakland suspect - were not arrested. The fate of the first shipment of 112 radiation-hardened chips - the ones that got away - is unknown. U.S. officials strongly suspect they are either in China or orbiting the Earth aboard one of Beijing's satellites. (Edited by Blake Morrison)