Telluride Film Review: ‘Tim’s Vermeer’

So entertaining that audiences hardly even realize how incendiary it is, “Tim’s Vermeer” stirs up a flurry of scandal in the hallowed realm of art history. Obsessive inventor Tim Jenison has a hunch that the only explanation for the photorealistic quality evident in the work of 17th-century Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer is that he “cheated,” using lenses or some other technological apparatus to achieve such remarkable detail. Jenison devises a five-year science experiment to test his theory, emerging with an uncanny crowdpleaser — the secret weapon in Sony Pictures Classics’ fall arsenal — that plays like the ultimate episode of “MythBusters.”

Generally speaking, Americans like their art easy to understand and difficult to make. Walk up to an all-white canvas or a minimalist watercolor, and the average spectator thinks, “How can this be art? Even I could paint that!” The tighter the technique, the more people seem to admire the craft, which is one reason Vermeer is held in such high esteem, having left behind nearly three dozen paintings that astound in their accuracy, despite having been rendered a century and a half before the daguerreotype (but not before the camera obscura).

So what if someone told you that anybody could paint as well as Vermeer? Is it still a masterpiece if an amateur could do it? Jenison has millions of ideas and just as many dollars, which affords him the luxury of indulging his pet theories. Here, for the benefit of magician friends Penn and Teller (the latter serves as director, while Penn Jillette supplies a fair amount of on-camera context), Jenison resolves to prove that one needn’t possess any God-given artistic talent to achieve what Vermeer did, if only he could pin down the combination of lenses, mirrors and other 17th-century tools the artist used to commit the scenes he composed in his studio to canvas.

As “The Da Vinci Code” proved a few years back, people love to uncover the secrets locked away in the masterworks of art history, and though “Tim’s Vermeer” does nothing to interpret Vermeer’s work, it sheds new light on the way he might have gone about it. Technically, the notion that Vermeer might have used a camera obscura as an optical aid has been around for years, backed up by mathematical calculations in Philip Steadman’s book “Vermeer’s Camera.” Jenison proposes an even simpler solution involving a simple hand mirror, enlisting both Steadman and “Secret Knowledge” author — and artist — David Hockney to test his theories as he goes.

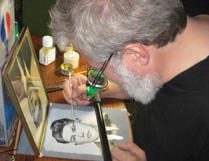

But Teller’s inventor/subject goes one step further than the scholars did, attempting to reproduce Vermeer’s “The Music Lesson” himself — and this is where the film crosses over into a fascinating tale of obsession, as Jenison uses his primary expertise (as founder of NewTek, he revolutionized the fields of computer graphics and digital video) to re-create the artist’s studio in a San Antonio warehouse. Using rendering tools to calculate the exact dimensions of every object seen in the original painting, from stained-glass windows to the models’ costumes, Jenison then constructs everything by hand and positions it just right in the room — a 213-day job, short by comparison with the actual task of painting.

One can’t help but laugh as Jillette supplies a running commentary on his friend’s lunatic scheme, for which (if Penn is to be believed) he even learned to read Dutch. Getting a perfectly calculated musical assist from master orchestrator Conrad Pope, whose score conveys the sheer intensity of Jenison’s focus, Teller observes the dedicated inventor grinding his own lenses, mixing period-appropriate oil paints and sitting down for months on end to create what, for all intents and purposes, amounts to a hand-painted color photograph of the scene.

“Tim’s Vermeer” is no mere art doc, however, as it places more attention on Jenison’s experiment than the process he’s attempting to uncover or the painter who inspired this bizarre journey. And though Jenison’s findings raise terrific questions about the nature of art (is Vermeer’s achievement in any way diminished if he used mirrors?), the extent of his genius (surely composition accounts for a great deal, no?) and the interpretation of his paintings (how to account for his presumed self-portraits?), Teller leaves such issues for someone else to consider. The result is just about the most fun you can have while learning, partly because it strips away any tangents beyond the task at hand, offering a lean, 80-minute account of how this crazy guy erected his own Everest and then proceeded to climb it.

Related stories

Toronto: 'Fifth Estate' Director Bill Condon Sets Sherlock Holmes Pic Starring Ian McKellen

Toronto: International Films That Have Festgoers Talking

Toronto Film Festival's British Invasion

Get more from Variety.com: Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Newsletter