Richard Corliss Remembered: A Great Critic of the Movies, and of Criticism Itself

We film critics have an often infuriating tendency to write as much about ourselves, and the state of our profession, as we do about the movies. This is hardly a new phenomenon, of course, but it may be more prevalent than ever before: Whether we’re seeking out pockets of online validation or trying to provoke those with whom we violently disagree (or both), the rise of social media has made it all too easy to engage directly with our ideological allies and adversaries alike. At the same time, the continual thinning of our professional ranks has fueled endless arguments and think-pieces about whether the Internet has succeeded in decimating or diversifying the field.

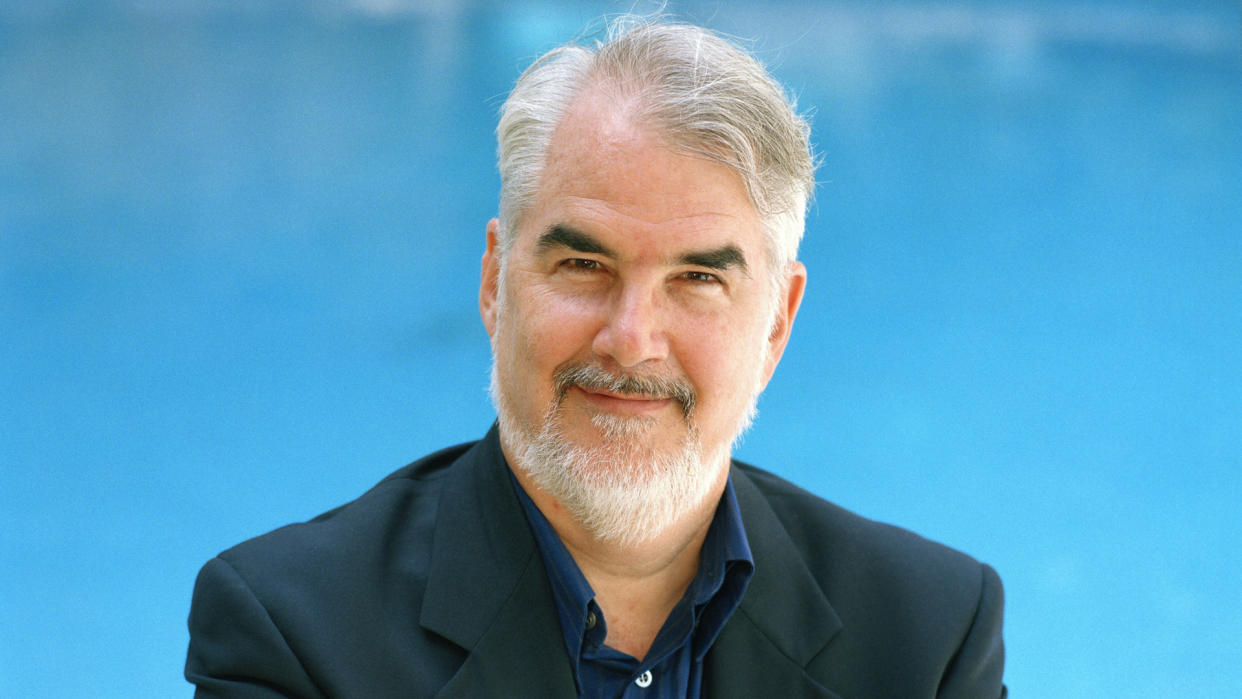

All of which makes it particularly important to remember Richard Corliss — not just because the veteran Time critic hailed from that honorable, not-yet-bygone tradition of wordsmiths who composed sharp, beautifully considered reviews for the printed page, but also because he was a master and a model when it came to civilly, and thoughtfully, taking his colleagues to task. Whether intentionally or not, he set himself up over the years as a sort of conscience to the critical community — a towering, goateed Jiminy Cricket who, every so often, would take time out from reviewing the movies to issue a gently barbed opinion on those aspects of the profession that troubled him most. Whether you agreed with him or not, his gripes, such as they were, conveyed far more humility than superiority, arising as they did from a searching, self-effacing and always generous intelligence.

As the recent documentary “Life Itself” reminded us, it was Corliss who, in 1990, took to the pages of Film Comment (the magazine he edited from 1970 to 1982) to write “All Thumbs: Or, Is There a Future for Film Criticism?” — in which he held up ABC’s “Siskel & Ebert & the Movies” as an example of the relentless oversimplification of film culture. To read that essay today is to be reminded that Corliss’ beef wasn’t really with his old friend Roger Ebert, a critic who did his own finest work outside the TV studio. Rather, he was taking aim at the sort of thinking that would reduce anyone’s opinions to the sum of their opposable digits.

Written well before the era of Rotten Tomatoes, tweetable audience reactions, and other Web-driven attempts to push movie consumption in the direction of a dubious consensus, Corliss’ piece now reads like a prescient, common-sense warning against received wisdom and lazy thinking in any form. Far from being an elitist or an anti-populist, he proved just as capable of turning his scrutiny on those critics whom he felt went too far in the direction of self-seriousness. “I don’t want junk food to be the only cuisine at the banquet,” he wrote. But then he went on: “I don’t want to think that all the critics who have made me proud to be among their number are now talking to only themselves, or to a coterie no larger than the one (Pauline) Kael and (Andrew) Sarris first addressed 30 years ago.”

It was easy to hear an echo of that warning when Corliss penned a Time magazine column in December 2007 titled “Do Film Critics Know Anything?” In that piece, he questioned the long-standing practice of critics’ group giving out awards — a practice to which he himself subscribed as a member of the New York Film Critics Circle and the National Society of Film Critics — especially insofar as they tended to favor films on the lower end of the commercial spectrum. On some level, he noted, this was a way for critics to participate in the Academy Awards’ promotional machinery while feigning superiority to it, perhaps to the satisfaction of little more than their own egos.

“In the old Golden Age days, most contenders for the top Oscars were popular movies that had a little art,” he wrote. “Now they’re art films that have a little, very little, popularity.” It was a curiously conflicted admission from someone willing to ponder what good these rituals and accolades, worthy though they might be, would come to in the end — whether they would accomplish anything beyond affording critics a fleeting moment of self-intoxication, like actually illuminating or edifying the audience. Corliss was toeing a fine line with that piece, and in far less delicate or knowledgeable hands, it might well have read like one of those noxious little “geek alert” screeds that seem to turn up whenever a critics’ group dares to think outside the awards-season box.

Happily, it didn’t, as that wasn’t remotely his sensibility. On the contrary, the body of criticism he leaves behind is notable not only for its elegance and erudition, but above all for its thrilling openness to every kind of cinema. Fittingly enough for someone who didn’t mind scolding the scolds, whatever the default setting of their brows, he drew precious few distinctions between the high and the low — or between, say, the visceral pleasures of a Zhang Yimou wuxia epic and the intellectual rigors of an Ingmar Bergman chamber piece. Here was a movie lover adventurous and engaged enough to name “The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King” the best film of one year and Werner Herzog’s “The White Diamond” the next. Here, too, was a writer unafraid to hold an unpopular opinion: I still remember a wonderful 2005 critics’ panel on “Charlie Rose,” where Corliss good-naturedly copped to being the only one at the table (which also included A.O. Scott, Lisa Schwarzbaum and David Denby) who had found something nice to say about “Memoirs of a Geisha.”

That episode flashed before my mind a little more than a month ago, when I happened to receive an email from a colleague that opened with this sentence: “Looks like Corliss bitch-slapped you in his Time review.” That struck me as odd, insofar as Corliss had never really struck me as the bitch-slapping type, and indeed, when I read the review in question, I was more honored than affronted to find that he had singled me out (and others) for panning the Will Ferrell-Kevin Hart comedy “Get Hard” — a movie that Corliss, with typically bracing honesty and good humor, was not ashamed to admit he had thoroughly enjoyed.

I have my own older, equally fond memories of Corliss. I first met him and Mary, his wife and equally movie-mad writing partner, at the 2012 Venice Film Festival; there we found ourselves, waiting outside the Sala Zorzi, in line for a super-early glimpse of Brian De Palma’s “Passion.” (Meeting them turned out to be the highlight of the morning.) And I confess that my heart leapt in my chest when Sight & Sound published the results of its 2012 international film poll, and I saw that Corliss was one of a handful of critics who shared my conviction that Wong Kar-wai’s “Chungking Express” was one of the greatest movies of all time. Richard Corliss may not have been right about everything, as he himself would have been the first to admit, but that was hardly the first or last time he managed to show us all how it’s done.

Related stories

Richard Corliss, Venerable Time Film Critic, Dies at 71

Get more from Variety and Variety411: Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Newsletter