NYFF: How 'Billy Lynn' Argues for and Against High-Frame-Rate Filmmaking

Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, which had its world premiere at the New York Film Festival over the weekend, finds director Ang Lee continuing to tinker with the art and science of crafting an intimate epic: a movie that offers grand spectacle while always remaining grounded in human emotion. It’s a quest he’s pursued since 2000’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, which used those celebrated gravity-defying martial arts set pieces as a sweeping backdrop for the impassioned tale of love denied unfolding in the foreground.

Lee’s subsequent forays into big-budget, effects-driven studio filmmaking — 2003’s Hulk and 2012’s Life of Pi — have also tried to both embrace and downplay the technology that makes them possible. Whether his subject is a digitally-generated green goliath or a motion capture tiger, he wants audiences to look past the F/X artifice and see the soul reflected on the character’s face.

Introducing Billy Lynn to NYFF audiences, Lee spoke about how Life of Pi in particular made him eager to pursue new ways of photographing faces. Hence this high-profile, high-risk experiment in high-frame-rate filmmaking. Shot in 3D at 120 frames per second (most movies are filmed at 24 FPS), the director uses the startling clarity afforded by that rate to invite viewers to closely examine the actors in his film as if we’re standing in front of them in real life. The image is so sharp, so revealing that the cast apparently had to go before the camera with little to no makeup lest a stray bit of eyeliner break the reality the film is striving to replicate.

Related: Steve Martin and Chris Tucker Talk ‘Billy Lynn’s Big Halftime Walk’

“I’m launching a new medium,” remarked a visibly nervous Lee, adding that we were only the second public audience to see the film. (Lee and his cast has previously introduced an earlier NYFF screening and stuck around for a Q&A.) “I hope you open your mind to a new kind of filmmaking.”

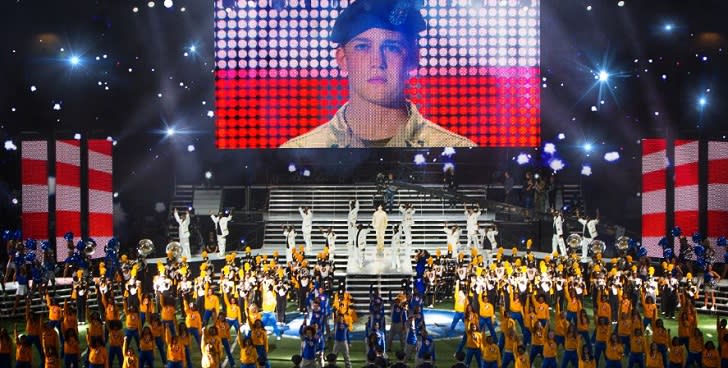

Perhaps some of the muted reaction expressed in the days since Billy Lynn’s NYFF debut can be chalked up to the fact that Lee uses this “new kind of filmmaking” to tell a fairly traditional story. Adapted from the book by Ben Fountain and set in 2004, the movie is an interior drama about one soldier’s brief return to the U.S. following an act of heroism on the frontlines of the Iraq War. Along with the rest of his squadron, Billy Lynn (newcomer Joe Alwyn) is reluctantly made part of a professional football team’s halftime show. (The NFL declined to participate in the film, so a team that’s pretty obviously intended to be the Dallas Cowboys has instead been given a generic name.) As the day unfolds, we watch as Billy’s buried emotions bubble up to the surface, enabled by latent PTSD as well as the exaggerated pageantry around him.

Although Alwyn is surrounded by a large ensemble that includes Garrett Hedlund as his company commander, Kristen Stewart as Billy’s anti-war sister, and Steve Martin as the team’s owner, the modest events of the film are very much filtered through Billy’s vision. From the first scene, Lee’s camera remains laser-focused on his leading man, inviting audiences to study his face often in tight close-ups, as memories of his wartime experiences are juxtaposed with the sizzle and flash of a sports spectacle.

Related: Review: Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk

The standout sequence — and the one that Lee cited as his inspiration for making the movie in the first place — is the halftime show itself, which has the razor-sharp clarity of most NFL games, with the league having been an early adopter of the high-definition format. More impressive than the fireworks and full-scale musical performance (Destiny’s Child is the featured performer, but Beyoncé and her former bandmates are played by stand-ins only glimpsed from behind) is the visible impact it has on Billy. Standing there in full public view, the full weight of his wartime experience crashes down on him at the precise moment when he can’t break.

Alwyn’s expression in that moments — stone-faced, yet achingly sad — embodies the promise of high-frame-rate filmmaking, and fulfills Lee’s stated mission of finding a new way for moviegoers to look at the human face on a larger-than-life screen. When the camera is still, the level of detail the director is able to capture is remarkable. Unfortunately, every pan or dolly shot is accompanied by a distracting stutter effect that resembles the dreaded “motion-smoothing” features on most TVs sold today. It’s the same problem that caused Peter Jackson’s noble experiment in HFR filmmaking — his Hobbit trilogy — to crash and burn with critics, his penchant for swooping camera moves adding an artificial layer atop imagery that was intended to seem wholly lifelike.

Lee’s calmer compositions make Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk an overall less assaultive HFR experience than The Hobbit movies. But there’s still enough adjustment time required to process the visual style that it’s all too easy for audiences to feel unmoored as the movie’s tricky tone and narrative takes shape. Although, to be honest, the director doesn’t always seem entirely certain what kind of movie he’s making either: clearly satirical moments are dropped almost at random into an atmosphere that’s often suffocatingly serious.

Still, reflecting on Billy Lynn several days after seeing it, I’m finding more things to appreciate about the movie, from Alwyn’s searing performance to Lee’s subtle, but pointed chiding of a certain kind of gaudy excess that’s passed off as patriotism. When the dust clears, and the history of 2016 is written, it’s doubtful that Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk will be credited with launching a new medium. It should, however, be remembered as one of Lee’s boldest artistic gambles.