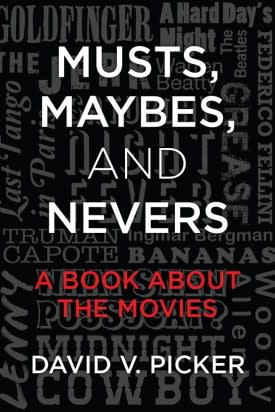

Living Legend David Picker’s Movie Memoir

Here’s a wonderful reason to interrupt my vacation: my longtime pal David V. Picker has finally published his Hollywood memoir – Musts, Maybes And Nevers. A one-time wunderkind who is 3rd generation film royalty, Picker at age 82 looks back on a legendary career that included running four different studios: United Artists, Paramount, Lorimar, and Columbia. Of course there’s a book party for him on October 1st hosted by Norman Lear, Tom Rothman, Mark Gordon, Larry Mark, and Bonnie Arnold who except for Lear all worked for David as assistants (as well as Jeffrey Katzenberg, Larry Kramer, and Jonathan Demme). Picker is a natural raconteur and this Amazon Digital book reads just like he talks and spins stories from the film industry during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. He could have penned an entire memoir just about the days he became UA President in his 30s and made all the early Woody Allen movies, read the James Bond books and brought them to the big screen with Cubby Broccoli, signed the Beatles to a 3-picture deal before they ever came to the U.S. and… Well, you get the picture. David provided me with the following nuggets to tease you:

The great director Billy Wilder once said to me, “David, there are only three kinds of movies – musts, maybes and nevers.” The phrase stayed with me throughout my many years as a studio executive and then a producer. That’s what this book is about.

It’s a book about what most people consider the last Golden Age of the studio film and United Artists, the studio I ran, was central to that golden hue. But it’s also a book about raging ego, and corporate involvement, and out of control talent, and the inner workings of a film studio – all of which is relevant to today. This is a book that will make people understand what the movie business can be, and has been, and isn’t any longer.

It’s a book about movies that I was actually part of – from getting Sean Connery to come back and do one more James Bond film and save the franchise, to getting Brian Epstein to clear enough time on the calendar of his clients The Beatles to film A Hard Day’s Night after I signed them a year before anyone had ever heard of them. What it was like in the 1960s and 1970s to run United Artists and create the very nature of the independent film business, a precursor to the Weinstein Company, Focus Films and Sony Classics of today. What it was like at United Artists in those years bringing to the company filmmakers such as Woody Allen, Ingmar Bergman, Sergio Leone, Norman Jewison, the Mirisch Company or Bernardo Bertolucci. To win Oscars with The Apartment, West Side Story, Tom Jones. Midnight Cowboy, Lilies Of The Field and subsequently, at Paramount and Columbia, Ordinary People and The Last Emperor.

But it’s not only about the successes. I’m credited with a famous quote in our business: “If I had turned down every picture I greenlit, and greenlit every picture I turned down, I’d have the same number of hits and flops.” Rob Reiner has told people it should be on my gravestone. So, yes, we’ll talk about the “misses” in some detail, too. And here are some of the questions that get answered:

Who wouldn’t want to work with Bill Cosby, the consummate self-centered egotist, at the height of his TV success? Me, that’s who. What happened at The Boarding House comedy club in San Francisco when I first saw an unknown named Steve Martin absolutely break the boundaries of stand-up comedy? Why would Stanley Kramer say to the studio that financed his film, It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, that he couldn’t and wouldn’t cut one frame from his four hour and one minute version of the film? Why would Robert Altman say to a friend of mine that he hoped I would die?How could a downbeat little book entitled Midnight Cowboy get made into a downbeat little movie that was sure to lose a lot of money? How was I able to work with, among others, Francois Truffaut, Claude Lelouch, Gino Pontecorvo, Ingmar Bergman, Philippe DeBroca, Sergio Leone, Elio Petri, Michael Cacoyannis, Louis Malle, Federico Fellini and Vittorio DeSica when the major studios wouldn’t go near them?

How could George Stevens, one of the best directors in the film industry, make the biggest flop in a company’s history based on a book that was the ‘greatest story ever told’ about the most beloved figure in the history of the world, not the movie world but the world world? What was it like to have a string of successes that led to the biggest year in Paramount’s history – pictures like Saturday Night Fever, Up In Smoke, Heaven Can Wait, Days Of Heaven and Ordinary People – then have the man who replaced you, Michael Eisner, take credit for all of them? How could a studio read the script of Planet Of The Apes or American Graffiti or Bonnie And Clyde and not say we have to make these pictures? Well, one studio said exactly that and I worked there. How could a neophyte executive insist that his boss approve an off the wall script of the 18th century novel, Tom Jones, and why did the boss give in? (And then they won an Oscar for their company.)

James Bond – briefly: Why did it take years (seven books worth) before James Bond came to the screen? Couldn’t any intelligent studio production executive see that Bond was a franchise waiting to happen? The answer is complex. Sometimes everything has to fall in place, then an opportunity arises and someone has to take advantage of the moment. Well, that’s what happened to 007. Lew Wasserman, the biggest agent in the business, was in New York and coming to meet with the UA brass. I had only been head of production for a couple of months when we all sat down in my boss’s office and I started the conversation. “Mr. Wasserman, you represent Ian Fleming. Why can’t we get the rights to James Bond? It would be great for Mr. Hitchcock – we’ve never made a film with him. It’s perfect.”

“It’s a great idea, kid, but Fleming just won’t sell.”

Oh well, not every idea comes to fruition, right? Some months later Bud Ornstein, the head of UA London production called and said that Cubby Broccoli and Harry Saltzman were coming to New York and they wanted to meet with Arthur Krim, Robert Benjamin, Arnold Picker and me. I set up the date. Harry, Cubby and Harry’s lawyer, Irving Moskowitz, sat in Arthur Krim’s office with Bob Benjamin, Arnold Picker and me. I usually sat to the left of Arthur’s desk, often with one of my long legs propped on the corner of the desk so I could tilt my chair back. Cubby was the first to speak. “We own the rights to James Bond. Are you interested?”

My leg came down and my chair hit the ground with a thud. And 007 began his screen life.

Let’s “tango” ahead 10 years… It’s September 1972, and I was buzzed to join Arthur Krim in his office where he had Jack Beckett, chairman of Transamerica, the conglomerate that owned UA, on the phone. As I walked in Arthur nodded for me to pick up the extension and he asked Beckett to repeat what he had just said so I could hear it as well. In Jack’s voice I heard both irritation and concern. I knew from experience that he was uncomfortable dealing with issues surrounding his film subsidiary, a business that was diametrically opposed in both style and content to the totally predictable insurance companies that made up the majority of the Transamerica family. They now had an arm that risked big bucks on a product where no one could project if it was going to lose the entire investment, or possibly make a profit. How could they have ever gotten into such a business? “David, Jack was just telling me that they are about to lose a $400,000 insurance premium in Arizona from a customer who says that Transamerica has just produced a pornographic movie.”

The call was motivated by a story on Last Tango In Paris in Time magazine featuring Marlon Brando on the cover. Although it was unclear if the reporter had actually seen the film, it was being interpreted in the article as ‘pornographic’. From United Artists’ point of view it was a gift from the publicity gods, almost guaranteeing the film’s financial success. From Transamerica’s point of view it obviously presented a financial problem. Beckett continued that Transamerica couldn’t and wouldn’t accept this problem and UA would have to give up distributing this film and sell it to some other company not so sensitive to Transamerica-type issues. Arthur looked at me and pointed to himself indicating that he would answer Jack. I nodded, not having a clue as to how he would deal with the gauntlet being thrown down.

“Jack, I hear you. So here’s what I propose we do. David and I will buy the film back from UA personally so there’s no further Transamerica exposure and then the two of us will be leaving the company and taking Last Tango with us.” There was a long silence and then Jack said, “I’ll get back to you on that.”

And that’s just a small sample.

Get more from Deadline.com: Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Newsletter