Charlie Chaplin's Tramp: A Classic Freudian Coincidence

Sigmund Freud said there are no accidents.

This story — of coincidences, not accidents — begins in early 1914 when a silent film newcomer at Keystone Studios swiftly picked out a costume. Under a tight deadline, young Charlie Chaplin was tasked with finding something funny.

He met the mission. And then some.

Still in his mid-20s, Chaplin didn’t realize his hasty choice of onscreen attire exemplified something deeper, and the character that would become inextricably part of his legacy.

Chaplin’s Little Tramp was “definitely subconscious … a tribute to his father’s stage character,” argues Jeffrey Vance, film historian and author of “Chaplin: Genius of the Cinema.”

Chaplin’s parents were both stage performers in the late 1800s. They earned very little money as he and his older brother grew up in London and Chaplin’s parents separated soon after he was born.

“He grew up in a lot of poverty,” Carmen Chaplin, grandaughter of the late performer, tells Yahoo Movies. “It’s very unique to go from that extreme poverty to that extreme of success.”

“Chaplin had an unresolved relationship with his absent father,” Vance says.

At 7, Chaplin was sent to a workhouse for the poor, later moved to a school for destitute children. By the time he was a teen, Chaplin’s father, an alcoholic, died from cirrhosis of the liver, and his mother was committed to a mental institution. Chaplin once described his childhood as “a forlorn existence.”

“I’m amazed with the willpower,” says Dolores Chaplin, grandaughter of the late performer and sister to Carmen. (Both grandaughters spoke to us at a private screening of their own films in West Hollywood on Thursday to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Tramp.) “The part of dream that he had and the way he constructed his life, always aiming for better — I don’t even have words for it. It’s very impressive.”

While it’s true that Charles Chaplin Sr., a well-known comic singer, was rarely around, he was responsible for his son’s first job as an actor, when young Chaplin joined the clog-dancing troupe “The Eight Lancashire Lads.”

“Chaplin’s childhood shaped not only his personality but also his art,” says Vance.

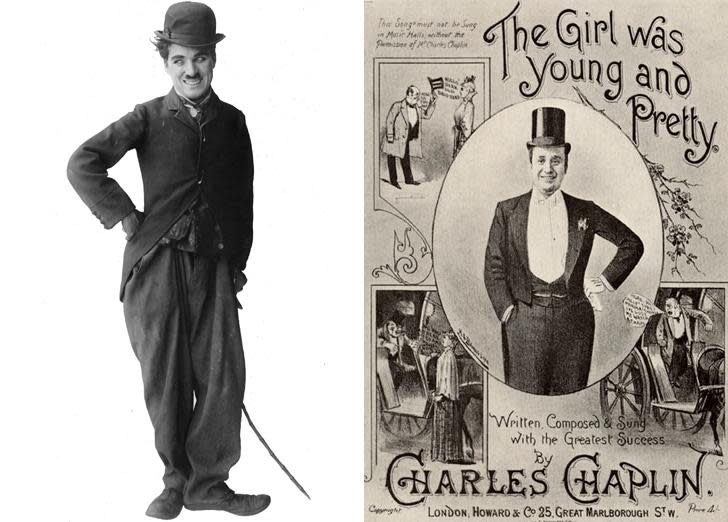

Chaplin’s father portrayed men-about-town in the English music halls. The Tramp shares at least one uncanny similarity with Chaplin Sr., Vance notes: “The Tramp’s gesture of placing his hand on his hip is very much something his father did on stage.”

[Related: Shirley Temple: How She Would Stack Up in Today’s Hollywood]

Chaplin drew from other childhood experiences, too: his mother (who, like the Tramp, would place her hand over her mouth when she laughed), tramp comedians of the English music hall where he and his father worked, the people of South London — “but mainly his father,” Vance contends.

“I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t trying to follow in my father’s footsteps,” Chaplin once said. Vance points to the big shoes of Chaplin’s Tramp: “A young son would perceive a father’s boots as big.”

The Tramp’s waddle, Chaplin told a reporter in 1916, was based on an old man named “Rummy” Binks who used to hold the coachman’s horses outside of his Uncle Spencer Chaplin’s pub in South London.

“I understand that the Tramp was inspired by this homeless guy that he used to see,” says Carmen Chaplin. “I think he must have been inspired by lots of different people.”

The late Chaplin would warn against unraveling his Tramp’s origins, saying, “I think you’re liable to kill your enthusiasm if you delve to deeply into the psychology of the characters you are creating.”

But Freud himself couldn’t help from speculating on the actor’s psyche, saying in 1931, “Now do you think for this role [the Tramp] he has to forget about his own ego? On the contrary, he always plays himself as he was in his dismal youth. He cannot get away from those impressions and humiliations of that past period of his life. He is, so to speak, an exceptionally simple and transparent case.”

[Related: Unpublished Charlie Chaplin Novel Discovered, Restored in Italy]

When Chaplin picked out his outfit and makeup for the Tramp, 100 years ago, he consciously set out to form opposites.

Chaplin recalled his boss, studio head Mack Sennett, biting on the end of a cigar and telling him, “‘We need some gags here. … Put on a comedy makeup. Anything will do.’” At that time, the new medium came quite awkwardly to the seasoned stage performer — Chaplin thought movies were shot in chronological order.

He rushed to the wardrobe room with no tangible direction except for the fact that he recalled Sennett wanting him to appear much older than Chaplin’s then-25-year-old exterior.

“I wanted everything a contradiction,” he wrote in his memoirs, “the pants baggy, the coat tight, the hat small and the shoes large.” Chaplin added the mustache as a last touch to age him, without concealing his facial expressions. “I had no idea of the character. But the moment I was dressed, the clothes and the make-up made me feel the person he was. I began to know him, and by the time I walked on to the stage he was fully born.”

[Related: Study finds most US silent films have been lost]

The persona, first seen in the 1914 short “Kid Auto Races at Venice,” was an instant hit — popular by summertime and known internationally by 1915.

Chaplin, a perfectionist, kept refining his famous Tramp. “Chaplin’s art comes into full flower with such films as ‘The Kid,’” Vance says of the late actor’s first full-length movie, starring Jackie Coogan as an abandoned child — arguably another Freudian wink back to Chaplin’s own childhood. “Of course it exemplifies his childhood because ‘The Kid’ is close to the poverty in which he grew up,” says Carmen Chaplin.

“Pointing to the humor in tragedy was one of his great gifts,” Vance says, listing films “The Gold Rush” (1925), “City Lights” (1931), and “Easy Street” (1917) as examples of Chaplin’s brilliant and unusual onscreen mix of pathos and comedy.

“Chaplin brought traditional theatrical forms into an emerging medium,” Vance adds. “He changed both cinema and culture in the process.”

“I think he was very lucky that [his childhood] inspired him and he transcended it,” Carmen Chaplin contends.

Though Chaplin himself may have said it best when he let everyone in on the genius behind his extraordinary brand of humor in his 1964 autobiography: “In the creation of comedy, it is paradoxical that tragedy stimulates the spirit of ridicule; because ridicule, I suppose, is an attitude of defiance: We must laugh in the face of our helplessness against the forces of nature — or go insane.”

Follow me on Twitter (@meriahonfiah)

Carmen and Dolores Chaplin hosted the 100th Anniversary of The Tramp event on Thursday in West Hollywood along with Mann & Miller with the support of Jaeger-LeCoultre and Alliance Renault Nissan.