He worked at Papa John’s in Durham. Now he owns the property and plans more than pizza.

That day in 2011, just after he’d quit his job at Papa John’s Pizzeria, Rakeem Chambers made a beeline for Durham’s 9th Street, just a few blocks around the corner.

That’s where Devil’s Pizzeria and Restaurant was. It had become a sort of refuge for the wayward teen, barely 19 and fresh out of high school. His friend Ziad Lobbab, already in his 20s, owned the shop. He was a bit older, more settled. He’d grown up in a Lebanese family, working at his parents’ restaurant next door, International Delights, a Durham institution for the last 30 years.

As Lobbab ran the ovens, the smell of hot oil and stewed tomatoes filling the air, Chambers slid into his favorite seat at the nearest table: “I plotted my next 10 years over a 10-piece buffalo wing.”

He pulls up the photo to prove it. In the frame, he’s seen sitting with the plate in front of him, still dressed in his red Papa John’s shirt, a wing in one hand, and a “middle finger salute” to his former employer in the other.

The photo is his final act of defiance. It’s also a reminder of how far he’s come.

Twelve years on, that once-defiant teen staring back who’d spent two weeks in juvenile hall is now a busy broker in Durham. He still eats at Devil’s Pizzeria most days, but the rest of his time he’s cutting deals and managing properties while slowly amassing his own real estate portfolio. Less than a year ago, he launched his own brokerage firm, Renaissance Realty. Now, he’s set to take on his biggest project yet. He and Lobbab — who still slings pies at Devil’s Pizzeria but invests in commercial real estate on the side — are developing their first major commercial property. And it so happens to be the old Papa John’s property where he once worked.

“Never in a million years did I think I would later purchase the Papa John’s building,” Chambers, now 31, says. “It brings our story full circle.”

Mixed-use project

Under the business name High Good, the pair bought the building at 106 Watts St. for $584,000 in 2019, according to tax records, along with a small adjacent parcel. By then, the dilapidated, 60-year-old building had sat vacant and abandoned for years. They leased it briefly during the pandemic, then demolished it last October.

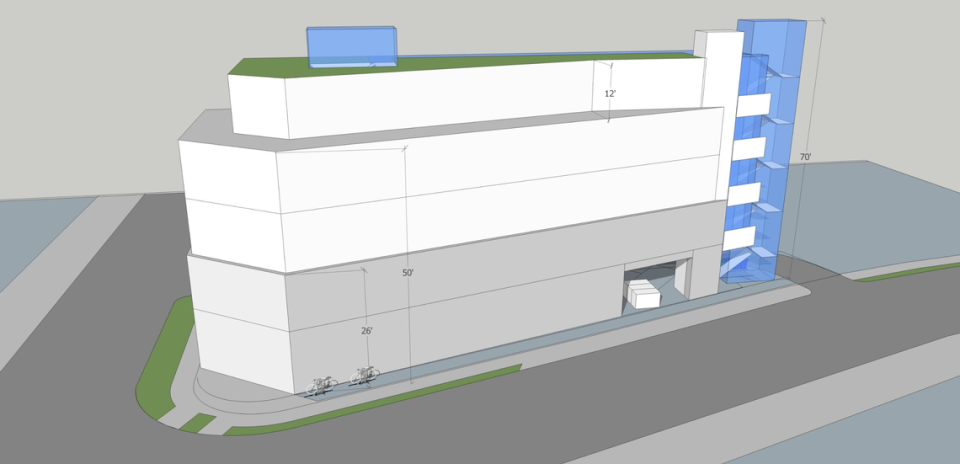

Now the two are aiming to build a five-story, mixed-use project on the .17-acre lot — shaped like a skinny slice of pizza — just a stone’s throw from Duke University’s campus.

Their vision: up to 17 condos, including two penthouses, totaling 16,500 square feet; 2,400 square feet of ground-floor retail and 10 parking spaces behind.

The estimated price tag: around $6 million.

Planning is still in its early stages, Chambers acknowledges. The pair still need to sort out financing and get final approval from the city, but he believes it’s the right development for this fast-changing corridor in Durham’s Brightleaf District.

“That side of downtown, from Thursday to Sunday, it doesn’t sleep,” Chambers says.

Next door is the Residence Inn by Marriot. Across the street is The Barlett, a seven-story, 34-unit complex that went up in 2019 and offers luxury condos priced from the $300,000s to $1 million. A 10-minute walk down West Main Street, a glassy 27-story high-rise called The Novus is under construction.

Chambers and Lobbab presented a preliminary review concept to city officials last year.

Durham planning officials confirmed they discussed the building’s proposed height and potential transportation issues. No rezoning or other approvals would be required, they said, “if it meets all of the unified development ordinance requirements.”

“The only peculiar challenge, in this instance, may be the peculiar shape of the property,” assistant planning director Bo Dobrzenski wrote in an email to The N&O this month.

Chambers isn’t fazed. “I designed the building myself. Everyone kept saying, ‘You can’t fit anything on this lot. It’s too small.’ But I kept saying, it can fit. It can fit.” He’s already getting offers to sell from developers who are looking to build nearby and add to their square footage, but he’s not budging.

“It’s like you’re playing a real-life Monopoly game.”

‘I’m an anomaly’

For Chambers, part of the game is also looking the part.

“That’s half the battle,” he says, speaking from his home office in Durham on this late February morning. Just like most days, he’s dressed in a navy, three-piece suit, “his uniform.” A white, French-cuff dress shirt peeks out from underneath, monogrammed with his seven-month-old son’s name, Maverick. He finishes the look with Cartier glasses “for his lazy eye.”

Like cornerback Deion Sanders’ famous quote: “If you look good, you feel good. If you feel good, you play good. If you play good, they pay good,” he laughs.

In today’s landscape where the people who buy, sell and manage commercial real estate are overwhelmingly white and male, Chambers doesn’t know of many other Black men getting into commercial development. “I’m an anomaly,” he says bluntly. As his mentors had warned him, “It’s a good old boys club,” he says.

A study released this month found that of roughly 112,000 real estate development companies in the United States, about 111,000 are white owned. At the top of the market, it’s even worse: Of 383 top-tier developers that generate more than $50 million in revenue annually, one is Latino; none are Black.

“There’s a stark representation crisis facing the real estate industry today,” said Derwin Sisnett, lead partner at Grove Impact, which released the report with the Initiative for a Competitive Inner City. “With Black and Hispanic developers making up under 1% of the field, it’s no surprise that diverse communities continue to face significant housing challenges.”

Among the barriers: a long-standing racial wealth gap that puts aspiring Black and Latino developers at a disadvantage for raising initial funds, a revenue gap for mid-sized Black developers and “revenue cliffs” for larger minority developers.

Despite their underrepresentation, however, many Black and Hispanic developers are successful, the study found. Indeed, small Black and Hispanic developers in their data — those with less than $350,000 in annual revenue — outperform their white peers. Black and Hispanic developers generated an average revenue of $170,563 and $178,319, respectively, compared to white developers, who made, on average, $159,591.

The city of Durham’s planning department said it doesn’t collect demographic information as part of its development review process. Consequently, it declined to comment on filing rates by Black developers.

Chambers’ accounts, however, mirror similar statements made by North Carolina Central University coach LeVelle Moton about the industry’s lack of representation. Moton co-owns Raleigh Raised Development, a minority-owned company behind the redevelopment of Heritage Park.

“Gentrification wouldn’t be so bad if Black people owned the land,” he told The N&O in November. “The problem with people that look like me is [they] haven’t had the chance to own or develop any properties.”

But that shouldn’t be the case, he said. “It’s important for us to develop these communities because it’s our communities. Who knows the needs of the people better than us?”

From pizza slinger to property developer

Chambers spent his early years in Connecticut where, he says, he didn’t have a lot of male role models. There was one exception: his great grandfather, Ervin Chambers Sr.

He immigrated from Jamaica at age 14 to Connecticut with only one change of clothes. Eventually, he got a job with the local aerospace manufacturer, Pratt & Whitney, and worked there for 30 years, investing in properties on the side, Chambers recounts.

“When he died at 86, he had four properties, managing roughly around 12 units,” he says. “I watched him collect the rents and do the maintenance on these properties. He always told me, “Hey Keemo, real estate is the way to go.’”

Chambers didn’t listen at first. By 14, he’d had a few run-ins with the police and served a two-week stint in juvenile hall. That proved the final straw for his mother. She promptly relocated the family to Durham where they had some family.

After graduating high school at the bottom of his class, Chambers got jobs working at Papa John’s and Harris Teeter, and later as a security guard. He also tried becoming a firefighter and, at one point, even considered joining the military, but recruiters never called him back. Eventually, he settled on working in the Wake County Sheriff’s Office, but knew he didn’t want to do that forever.

“It just wasn’t impactful enough for me to touch the things around me, like my community,” he said.

Around that time, he started binge watching YouTube videos of New York real estate developer Don Pebbles and reading his books. As founder of Peebles Corp., he’s one of the wealthiest African-American real estate developers in the nation.

Seeing a Black man in that position, Chambers says, was the tipping point for him. In 2015, at 25, he got his real estate license. And within his first year in residential sales, he cleared about “$6 million in sales volume,” and won “Rookie of the Year” at his agency.

Eventually, he was recruited by Domicile Realty to sell custom homes in Chapel Hill’s Governors Club. Despite the high commissions, he saw others at his firm acquiring land and developing sites “at three times their investment,” and he also wanted in.

One mentor warned him that it wouldn’t be easy, but “with these big dreams and tenacious attitude, I was like, ‘I’m gonna do what it is that I want to do.’”

Chambers recognizes that he still faces hurdles with his latest project. In the meantime, he’s leasing the site to food trucks to cover interim costs. He’s also serving on the Durham Historic Preservation Commission, and taking evening classes in financial analysis to become a certified commercial investment manager (CCIM), the gold standard for brokers and developers.

“Still to this day, I aspire to be something like Don Peebles of my generation,” he says. “I want to take a piece of land, and I want to build buildings. Real estate is a way to color things around me. To add life, give hope.”