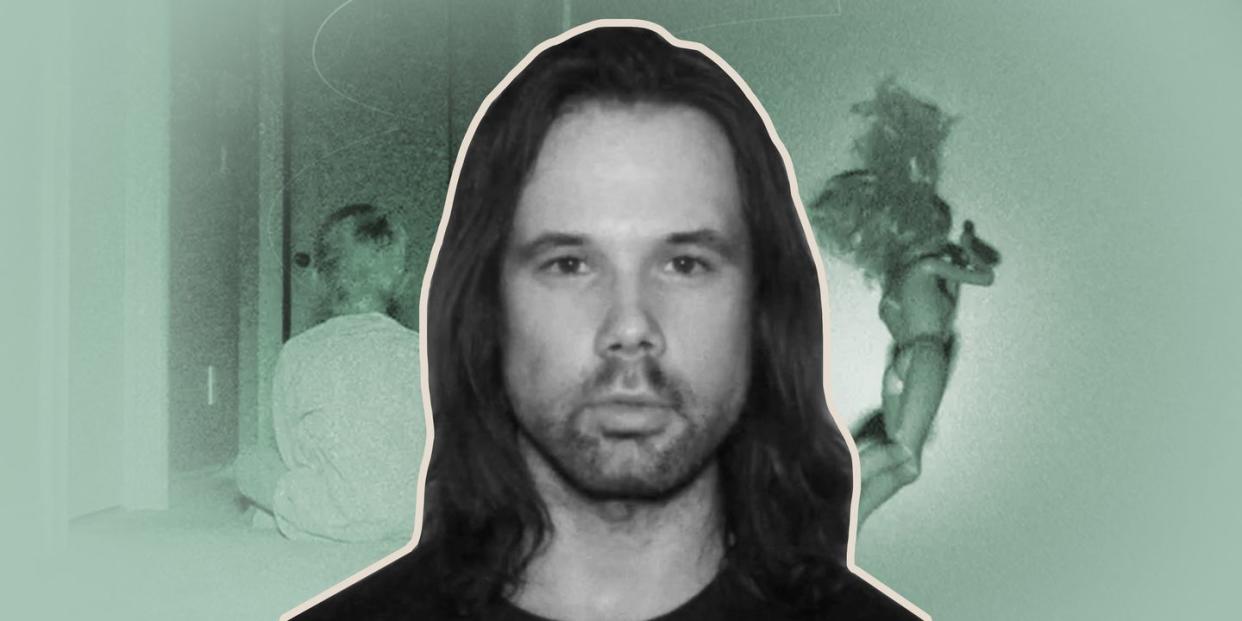

Why 'Skinamarink' Scares You Shitless, According to the Man Who Made It

When I meet Kyle Edward Ball, the soft-spoken and thoughtful director of viral, vibes-forward horror hit Skinamarink, I mention that my friends and I have been jokingly turning the title of his movie into a verb: "Getting Skinamarinked." It gives him a good laugh. "That's been interesting—the different names that people call the monster," Ball says. "The monster in the script is always referred to as just 'Voice in the Dark.' But people call it the Entity, the Demon, the Skinamarink, the Monster."

Movies like Skinamarink, where so much is left up to interpretation, take on a life of their own—becoming a sort of colloquial shorthand, as well as a collaborative experience. It probably why, after running the festival circuit over the summer, Skinamarink received a theatrical release in January, where it grossed a whopping $1,150 per screen. But Ball, while speaking to me ahead of his movie's streaming premiere on Shudder, mentioned how much fun he has looking up everyone's galaxy-brain fan theories. "First of all, every fan theory is true, and every fan theory is false," he explains. "Someone had a theory that I'm the monster. And then someone had a whole theory based around the dollhouse that appears in the movie, that they're all in the dollhouse. That's so neat, right?"

It helps that Skinamarink's plotting is purposely oblique. All the viewer knows for certain is that two small children—a little boy, Kevin, and his older sister Kaylee—are left alone in a house that seems to be under the control of an evil presence. The doors and windows to the outside are disappearing, leaving the children in darkness lit only by a television playing old cartoons and a hallway night-light that keeps being pulled from its socket. A deep voice whispers softly to the children, luring them up and down the stairs. Their toys disappear and reappear stuck to the wall... or the ceiling. Skinamarink's slow burn easily makes it one of the scariest movies of the past decade. And Ball knows why.

"I think it's hard not to identify so deeply with the story because we've all been little kids at some point, and we've all been afraid," Ball says. "Growing up, that never really goes away. I feel like I'm 31, physically and intellectually. But emotionally, I sometimes feel like I'm still five years old, and any appearance of emotional development is just my intellectual development keeping my emotional development in check. I feel a lot of the time we're all just five-year-olds in grown-up bodies wandering around."

Skinamarink is set in 1995 and was filmed inside Ball's childhood home in Edmonton, Canada. The house's wood-panel walls and piles of plastic toys instantly strike a nerve with those who remember childhood in the analog era, left alone while the adults are off on some mysterious errand, watching as familiar rooms, hallways, and pieces of furniture become sinister and strange. Skinamarink scares, when they come, are extremely effective—but most of the movie is enveloped in this weird, evil vibe, thanks to long, off-kilter shots of empty hallways, doors slightly open, and straight-up pitch-black darkness. Ball says a friend's description of the video game Silent Hill 2 inspired him. "It always stuck with me the way he described it," he says. "There'll be hours in the video game where nothing happens. You're just walking around doing nothing. And after a while, it becomes so unnerving and creepy. I went in with that mindset a little bit for the movie."

So, yeah: paradoxically, Skinamarink's less-is-more approach makes the scary bits even scarier. Toward the end of the film, there's a memorable jumpscare involving a toy phone, which Ball admits is "objectively the cheapest one." And yet! It works. "That one was the hardest one to do," he explains. "Originally, it was something completely different. I had to come to it. I've heard anecdotally, after that happens, there's laughter in the audience, which is the perfect response."

Seeing Skinamarink with an audience is an absolute delight, don't get me wrong. That said, since the movie is set inside a spooky house, Ball thinks it might be more effective—or effective in different ways—to watch it at home. "Granted, at home, you do have to do things to make the environment scarier," he says. "You have to, ideally, have it as dark as possible, as late as possible, as quiet as possible, as loud as possible. I do find with a service like Shudder—which is so receptive to horror fans and geared toward horror fans—a lot of the people watching it on Shudder will go to those lengths to make it as scary as possible. And sometimes it could even be scarier at home. Most of the horror movies I've seen in my life I have seen at home."

There's a found-footage aspect to Skinamarink, which feels like it was cobbled together from cameras that were littered around inside this house, most of them pointed at nothing in particular. Most of the action happens off to the side, with a digital grain superimposed on the image that obscures all detail—making it impossible to tell, sometimes, if the figures you're seeing are actually there, or just in your imagination. Ball developed his style while making horror shorts on his YouTube channel Bitesized Nightmares, crowdsourcing his viewers' childhood fears and bringing them to life. "I didn't have the budget to show people all the time, and when I did I couldn't really focus on their performance because I was just shooting my friends and they're not professionally trained actors.," he says. "After a while I kind of developed that into an aesthetic and a feel and a style."

"I was jealous of people who made movies in the '60s and '70s because I thought, Well, they get to make old movies and I can't," Ball adds, while describing how he came to Skinamarink's lo-fi aesthetic. It feels in line with social media's recent move toward art that feels older and more intimate: bedroom pop, overexposed Instagram filters, 35mm photography. "I feel like it was a foregone conclusion that at some point, we would have this reactionary movement, where things have gotten so high-res, so crystal-clear, so perfect-looking and perfect-sounding, that it was only natural that people would start saying, 'Let's go back.'"

A glitch in an online film festival website allowed Skinamarink to be downloaded and pirated months before its official release in January, with horror evangelists on YouTube, Twitter, and TikTok praising the movie for its visceral frights and spooky atmosphere. The response when it finally opened in theaters was a little more polarizing. The slow nature of the storytelling leaving a lot of viewers baffled, wondering what exactly they'd just seen.

"A lot of people don't like the movie. They've said stuff like, 'It's just doors. Just hallways,'" Ball says. "I don't want to sound indignant, but there's a little bit of a classist element to that. Number two, what do you look at in your house when you do get creeped out at night? It's just other stuff in your house. Like a door that's ajar, or your cat meowing in the middle of the night. Or the classic thing with a pile of clothes, but maybe it looks like the ghost of an 18th-century demon child when it's 2 A.M. That's what we live through. And it can be pretty scary at night. I wanted to try to replicate that."

Watch Skinamarink, At Your Own Risk

You Might Also Like