Why One Design Studio Is Offering a New Vantage Point on Black Protest Art

“Hearst Magazines and Verizon Media may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below.”

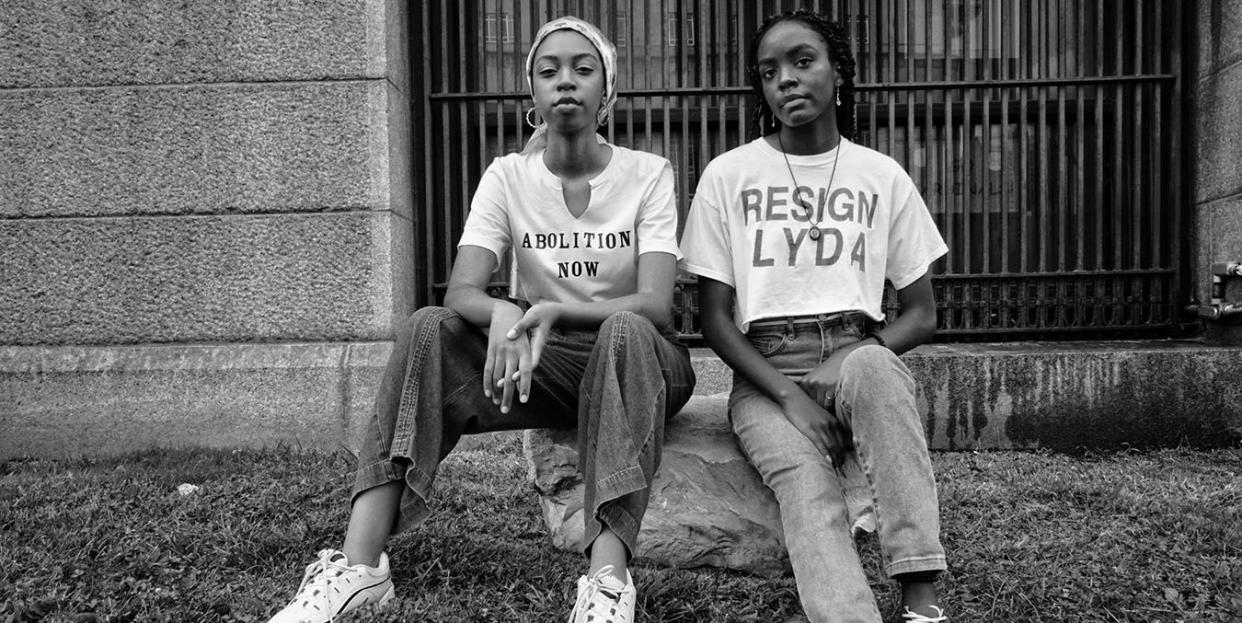

Above: A photograph by Vanessa Charlot from TRNK’s “Resistance::Resilience” exhibition.

This Black History Month, TRNK founder Tariq Dixon wanted to use his platform to directly address the Black Lives Matter protests of summer 2020 and to imagine a way that he, as a Black retailer and the head of a design studio, could affect change. The result is the latest installment of the TRNK Editions art series, “Resistance::Resilience,” a collection of photographic and mixed-media works that aim to contextualize the history of Black activism in the United States.

The exhibition brings together diverse perspectives on protest and its implications for the Black American experience from the likes of Amandla Baraka, Gregory Prescott, and Quan Brinson; the works are available framed and unframed, starting at $150 each, with 25 percent of sales throughout the year benefiting the Black Youth Project 100, a member-based organization of Black youth activists. We spoke with Dixon about the curatorial process, art as activism, and collecting what you love.

ELLE Decor: How did you consider the audience for “Resistance::Resilience”? These are very specific works made by Black artists in a very specific context. How should a non-Black person engage with this work? What is their entry point?

Tariq Dixon: One of the intentions was to redefine protest art, to some degree. It was important to us to celebrate this movement and the visual thinkers in the movement, but we didn’t want to do that from a singular point of view and we didn’t want that point of view to be trauma and struggle. We did want to include actual documentarians who were photographing Black Lives Matter protests, but it’s not just about documenting arrests or violence; those works still depict both humanity and power. And there are other works that don’t directly engage with the recent protests but are still inherently political. The irony is that mere Black identity and existence is still a political act, and I think that’s what a lot of the artworks are conveying. Even the question around the universality of this art, the fact that it’s not assumed to be universal, speaks to the fact that it is inherently political.

ED: What were your criteria when selecting works for the exhibition?

TD: I was often led to artists because of their work about the protests, but selected pieces for the exhibition from their entire body of work. There are so many different ways to depict Black strength and resilience; some photographers used models or staged vignettes. I really wanted to make sure we included documentary-style photography, but also graphic work that was used in protests or created for social media to amplify the movement. We ended up curating only one work that fit that bill, the All Black Lives Matter poster by Joanne Petit-Frère. How the show looked in the end evolved because of how much I learned in the process.

ED: How collaborative was your approach to this show?

TD: The process was similar to our previous exhibition, summer 2020’s “MIEN,” in terms of discovery and outreach, but my understanding of protest art and what could fit within that rubric was definitely broadened in conversation with the contributors. For example, Myesha Evon Gardner suggested her barbershop series to me as a story of community and camaraderie, for Black men especially, where you can depoliticize your identity for that brief moment. I found that story so compelling, and it fit so perfectly within the show’s overarching narrative of resilience.

ED: Did the photographers you approached all have a background in fine art, or was it a mix?

TD: It’s a complete mix. Some of them did commercial photography: Anthony Geathers primarily shoots sports; Amandla Baraka shoots fashion campaigns; others, like Felli Maynard, have a more traditional fine art practice. But I see these pieces, from everyone involved, as part of a fine art practice, even if it’s a personal practice that hasn’t been formalized on exactly those terms yet. That was consistent. The work was personal.

ED: What’s your advice for someone just starting to collect art and photography?

TD: First and foremost, finding works that compel you, whether you align with the thinking behind them or just find them visually stimulating. How they integrate with your decor is secondary; if you love a work it will naturally find a way to integrate seamlessly with your space. That’s why it’s important to curate this work for us as a design studio. People are supposed to live with these products, these images. For me, certain images can provide calm or evoke reminders of strength and humanity and persistence—those are messages that we could all stand to be reminded of on a daily basis.

You Might Also Like