Why did the KGB steal Jimi Hendrix’s hand? Ask Ukraine’s top comic novelist

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The western Ukrainian city of Lviv has been through a lot: not least a lot of names and nationalities. Before it was Lviv it was Lwów, part of the Polish Republic, and before that it was Lemberg during the period of the Habsburg empire. The Polish novelist Józef Wittlin wrote in 1946 of the city’s “extraordinary mixture of nobility and roguery, wisdom and imbecility, poetry and vulgarity”, as well as its “abhorrence of solemnity” and “dislike of all manner of pomp”.

To Milan Kundera, this “nonserious spirit that mocks grandeur and glory” is the result of eastern Europeans too often being the “victims and outsiders” of history. Certainly, Ukrainians today know all about that, and their experiences have been well chronicled by the Ukrainian novelist Andrey Kurkov, best known for Death and the Penguin, whose satirical, emotive, antic writing captures the “screwball strain” that Philip Roth loved in literature from the region.

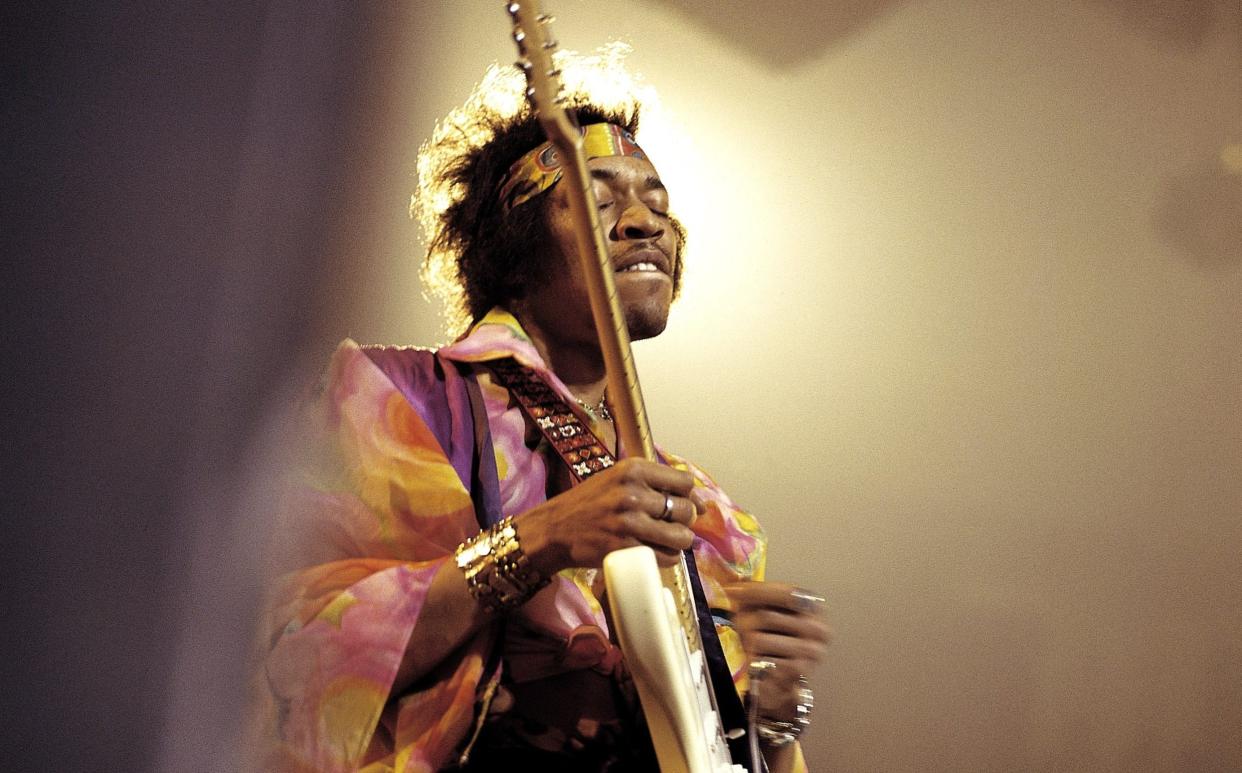

Kurkov’s latest novel to appear in English, published originally in Russian in 2012 and now translated by Reuben Woolley, has just been longlisted for the International Booker Prize. The title – Jimi Hendrix Live in Lviv – sums up much about the book: it is eccentric, curious, misleading, and a bit silly. It should perhaps be called “Jimi Hendrix Dead in Lviv”, since we’re told near the start that the KGB stole Hendrix’s right hand several years after his death and buried it in Lviv, so that fans “had somewhere to commemorate him on the anniversary of his death!”

The person telling us this is Ryabtsev, a former KGB captain whose love for Hendrix stalled his career progression. On the 41st anniversary of Hendrix’s death, at the grave he bumps into Alik, an old hippie Ryabtsev used to spy on. “We were close. Against your will, of course.”

And so Alik and Ryabtsev strike up a reacquaintance and, like many of the characters in the book, do a little capering dance around one another for a time. Eventually, a plot of sorts develops, as gulls and starfish appear in the city, and smells of the sea fill the air. This is odd, since Lviv isn’t near the ocean (it doesn’t even have a river), and Ryabtsev, with all the paranoia required of an ex-KGB man, finds that the city was built on the bed of a prehistoric Carpathian sea, and fears that “the sea is returning, rising up from the earth, leaking out”.

Meanwhile, we meet Taras, a man who makes a living driving people over Lviv’s cobbled streets in his clapped-out Opel, which helps to push out their kidney stones in an excruciatingly painful process. “Vibrotherapy usually removes the stones in two to three hours…” For his trouble, Taras earns $30 and gets to keep the stones.

Well, it’s a living, after all, and the book is full of people trying to make ends meet. (“Capitalism is a violent thing. If you want to eat, best get to work!”) There’s Taras’s neighbour Yezhi, who cuts people’s hair in his flat. Taras worries that he’ll end up like him, “cutting your neighbour’s hair… just so someone will listen to you!” And there’s Darka, a bureau de change teller who is allergic to money, and with whom Taras falls in love.

There’s a sort of manic levity throughout the story. It’s all good fun, but it isn’t subtle: we’re told that Alik is an old hippie almost every time he appears, and many lines of dialogue end in questions, exclamations, or both. (“Do you want to give yourself an ulcer?!” “Where do they take the piss-pants?!”) Characters pop in and out of scenes with the brio of sitcom regulars: when Taras’s old friend Oksana appears in his flat with the words, “I was passing by”, I could hear a studio audience applauding in delighted recognition.

You may at times wonder where it’s all going – or, indeed, where it’s all going?! The answer is mostly round in circles, though the plot builds as gulls start attacking people. (“[Taras] remembered the Hitchcock film,” we’re told, helpfully.) But the satire doesn’t sink very deep, even if I did find myself coming to love the bunch of misfits that Kurkov has assembled for our entertainment.

“We’re all sadomasochists here, but you really take the biscuit!” says one character to Alik. Well, I wouldn’t go that far. You might not be missing much if you don’t read Jimi Hendrix Live in Lviv, but you’ll probably enjoy it if you do

Jimi Hendrix Live in Lviv is published by MacLehose at £16.99. To order your copy for £14.99, call 0844 871 1514 or visit Telegraph Books