What it’s like to be fired as an NFL coach

He had planned to sleep at his palatial office. Shut his eyes in darkness. Open them to light. He’d peer out his window. Survey a well-manicured lawn. Then get to work. Because he loved his job. He really did.

He was a 38-year-old Midwestern transplant, who after three nomadic decades had found a home out west. Work had initially lured him to Los Angeles. Life had attached him. He’d graduated from early adulthood here. Learned a ton. Married. Had kids. He’d traveled north for a payday, then bolted east for a “great job,” then returned for his “dream job.” And in September 2013, even as he struggled, he couldn’t imagine leaving it.

Until, on a return flight after a business trip, he got the note. His boss wanted to meet. Not tomorrow. Tonight. And not in his office, not even at company headquarters, but in a private room at Los Angeles International Airport.

Six year later, the scenes flicker back into his mind. He grabs his luggage, a bit confused. He steps off a bus. Crosses a tarmac. Drags himself into the private room.

And at around 3 a.m., with his family sound asleep, he gets fired.

He fights. Not physically, but verbally; emotionally. He’s desperate to state his case. His boss steps out of the room to make a phone call – perhaps, he hopes, to reconsider – then returns to say it’s too late. So after an hour of pleading, he slumps into a car, his body weary, mind spinning. When he arrives home, he wakes up his wife. She’s surprised. He explains. They’re both crushed.

He tries to sleep. He can’t. As the sun begins to rise, his phone begins to ring. He doesn’t answer. He’s angry. Stunned. And he knows. Knows that he’s national news. Knows that the thousands of people who wanted this to happen, who wanted him to suffer, who wanted him to lose his job will soon hear exactly how he lost it. They might even celebrate.

Someday, his three kids will hear, too. For now, he’ll try to act as if nothing’s changed. He’ll have more time for them. He’ll take them bowling. But when he does, strangers’ eyes will hound him. He’ll pull his hat down over his face. He won’t be able to enjoy his daughters’ smiles. And before long, he’ll have to uproot them. Pull them out of schools. Sever their friendships. Again.

Because he is not your average 38-year-old corporate executive. His name is Lane Kiffin. And his profession is football coach.

The human element

There are 32 head coaches in the NFL. Thirty-two men at the top of their profession. Thirty-two driven employees whose successes and failures are intensely public. There are hundreds more in college. And every winter, dozens of them experience what Kiffin did six years go; dozens of them lose their jobs.

Which, in any normal context, would be absurd. Eight NFL head coaches were canned last season. A quarter of the 32. Twelve months later, four more have been fired and two more could follow.

The churn is one of many accepted absurdities of a very abnormal industry. One that pays extraordinary wages for extraordinary hours and extraordinary work. One where, when the dawn-to-dusk days don’t yield results, customers instantaneously become aware and impatient.

Coaches become the natural scapegoats. They become hashtags and chants, their names fused to the word “fire” by superglue. Journalists call for them to lose their jobs. Before they actually have, prime-time TV and radio shows speculate about their successors.

And they get it. They really do. They are privileged, blessed, the 1 percent both in society and their line of work. They could do without the line-crossers, the front yard-trashers, the verbal abusers. Everyday passion, however, is why they make as much money as they do.

But what gets lost in the abnormality is that they are still human beings. Yes, they get paid millions. No, exchange rates for dollars and happiness do not exist. Yes, their families are financially stable. No, stability does not mute their emotional pain.

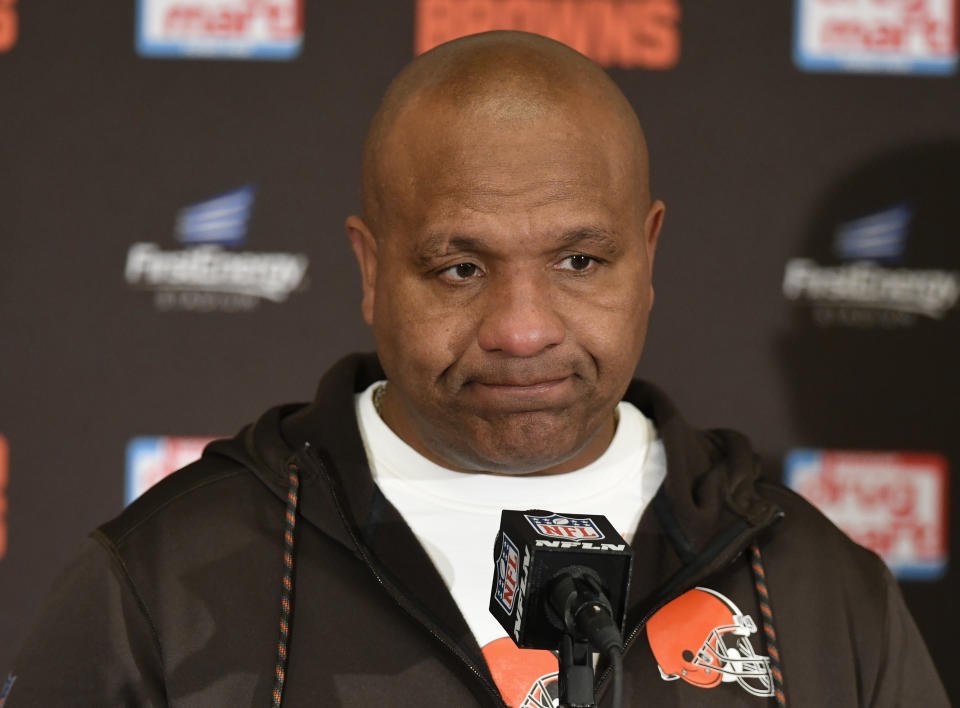

They understand that you will never understand. Sometimes they wonder if maybe, just maybe, you’d try. Because if you could see the inner turmoil; if you could see Hue Jackson descend into his basement, into “hell,” and not emerge for three days; if you could see the stares that Kiffin got at that bowling alley, the ones that seemed to whisper, “There’s the guy that screwed up USC”; then maybe, just maybe, your attitude toward your team’s sputtering coach would be slightly different.

“If people knew that side of it,” Kiffin says, “I don’t think they would root for it so much.”

In search of a peek at that personal side, Yahoo Sports reached out to over a dozen once-fired NFL head coaches. Most, understandably, declined to speak on the record. But Kiffin and Jackson agreed to. And their accounts provide a revealing window into the darkest realm of their profession.

Firing day

The first time Lane Kiffin got fired, there was no knock on the door. No scheduled meeting. Just a call to his Oakland Raiders office phone, the one nobody ever dialed. Except Al Davis. So Kiffin picked up. “It was very short,” he recalls. “He just said, ‘I’m firing you. … And make sure you turn in your car keys.’ ”

Kiffin says he did not have a team-issued car from the Raiders. “It was bizarre,” he says.

Next thing he knew, he was being escorted out of his office in a state of “shock.” He was initially told he had 30 minutes. He was eventually granted more. So through the building he went, down the hall, then downstairs, saying as many goodbyes as he could. To his assistants, the ones he’d spent hundreds of hours in meetings with. To a few players, the ones who’d fought for him. To an athletic trainer, to other Raiders employees.

“Everybody tells you what you want to hear,” Kiffin says. “Like, ‘Oh, I can’t believe this, you were my favorite.’ ”

Every firing, in this regard, is different. The Redskins summoned Jay Gruden to the team facility at 5 a.m. the Monday after a Sunday loss. The Panthers axed Ron Rivera on a Tuesday, the players’ day off. The team then allowed Rivera to return on Wednesday to address those players one final time; to hold one final news conference; to meet with coaches one final time, to ensure a peaceful transfer of power. Rivera, though, was an exception. He’d spent nine years in Carolina. Day-after gatherings like his are rare.

Jackson, who was in the Raiders chair three years after Kiffin, describes his first firing as fairly typical. Nine days after an 8-8 season, the franchise’s joint-best in nine years, he received a message from newly appointed general manager Reggie McKenzie, inviting him to meet. “I’m thinking we’re gonna talk about the team,’ ” Jackson remembers. About the roster, offseason plans, visions for the future. McKenzie, instead, told Jackson he was being let go.

“And I go, ‘Huh?’ ” Jackson recalls. “And he goes, ‘Yeah.’ ”

He quickly cycled through confusion and disappointment. Understanding would come later. He scrambled to grab personal belongings. To turn in workplace keys and credit cards. He just wanted to escape. “You know you need to leave the building,” Jackson says. “Because once it hits the media, people are gonna show up, people wanna stick a microphone in your face.”

Which is why office-clearing is often done at a later date, and often by someone else. Pictures, scrapbooks, notebooks, playbooks are packed up and shipped to the ousted coach’s house. Unless, that is, the team has other ideas. Jackson says he has seen battles over various physical representations of a coach’s football knowledge.

“And you’ll laugh when I tell you this: Some people don’t let you take it,” he says of the notebooks and playbooks. “Some people say, because you created it in their building, it’s theirs, it’s their property. And normally that’s a huge fight.”

But there’s no time for it in the moment. The news leaks. Calls, texts start coming. You take, or make, the important ones. You ignore the rest. You drive home with the windows up, radio off. Kiffin remembers rolling past the horde of cameras, through Alameda County, away from what he now calls a “toxic, miserable environment,” toward his family.

You talk to wife, kids, close friends in the business. But their condolences, in many cases, are futile. “You’re hurt,” Jackson says. “Let’s just be honest. You’re hurt. You’re a hurt person. … [Others] can understand it, but you have to get through that yourself.

“And I understand that more so now,” he says, a year removed from a firing that affected him in ways he didn’t think possible. “More so than ever.”

You ask yourself, ‘Why?’

Jackson’s second firing infuriated him. It was Oct. 29, 2018, a previously uneventful Monday in Cleveland. “I felt anger. Betrayal. All kinds of things,” he says. So he told his boss to “get the f--k out” of his office. And then he got the hell out, too.

“When you’re doing a sh---y job, you normally know. And you can live with that,” he explains. But when you don’t feel that, and the axe still falls? “These are the other emotions that will attack you. You ask yourself: Why?”

He had never experienced those emotions before, the ones that pushed him down his basement steps and wouldn’t let him come back up. “You’re in hell,” he says of the three days he spent down there after the Browns let him go. “’Cause you’re questioning everything. You’re trying to figure out everything. You’re questioning everybody’s motives, intentions.”

He couldn’t bear the thought of human interaction, couldn’t bear the thought of the outside world. He was depressed. The thought of his wife and three daughters eventually pulled him up those stairs. But he wasn’t himself.

Because for 32 years he was a football coach, and now he wasn’t. His profession defined him, his performance a constantly oscillating measure of self-worth. At times, if not all the time, he’d forget to check in on his own humanity. He’d refuse to acknowledge feelings. He’d throw up in trash cans rather than take sick days. “There’s times I’ve gotten an epidural in my back and gone right back to work,” he says.

So when there was no work, he felt lost. In the absence of football, after a while, he realized that he could, in fact, feel. That it was natural. That his human emotions were just like yours and mine, and that it was OK, necessary, to grapple with them. “The mental side,” he says, “is invaluable if you understand it.”

Coaches, he explains, aren’t equipped to. “Coaches are equipped to work and coach and drive,” he says. To spend 16-hour days at the facility. To maybe spend the occasional night as well. To work themselves into exhaustion, exhaustion that can hospitalize them but rarely stops them. “We only know [one] world,” Jackson explains. “Find a way to get it masked and move on.”

His Browns-imposed sabbatical finally allowed him, forced him, to consider a healthier world. “When you’re in high stress during the season, you don’t want someone talking to you about your mental health,” he says. “A lot of people are afraid to find out mentally, emotionally, where they are.” In 2019, with stress relieved, he overcame that fear.

The stress will return someday if he gets his wish. He wants to coach again. To prove people wrong. To return to the only life he knows. Only now, he’ll be able to live it having realized what so many fans, so many outsiders, and even many of his peers never do: That he is human like the rest of us.

That losing a coveted job sucked for him as much as it sucks for you.

That he is stronger, tougher because of it – but still working his way through. “I don’t know that you’re ever [all the way] through it,” he says. “The wound is still the wound.”

Kiffin, until recently, thought he was over it. Then he picked up the phone on a recent Wednesday afternoon, 10 days before he’d be announced as the new head coach at Ole Miss. He spent 40 minutes over lunch rehashing those dark moments, outlining why his USC firing was undeserved. As he stated his case, the same one he laid out for athletic director Pat Haden that night at the airport; as he spoke about scholarship penalties and their restrictive impact; as he explained what a setback that night had been for his career, his voice bubbled. Sped up. Acquired an edge.

A little after 2 o’clock, it subsided to room temperature. Kiffin needed to get back to work. His final regular-season game at Florida Atlantic was days away. But first, his own realization.

“God,” he thought to himself as he prepared to move on with his day, “maybe I’m not over this.”

More from Yahoo Sports:

– – – – – – –

Henry Bushnell is a features writer for Yahoo Sports. Have a tip? Question? Comment? Email him at henrydbushnell@gmail.com, or follow him on Twitter @HenryBushnell, and on Facebook.