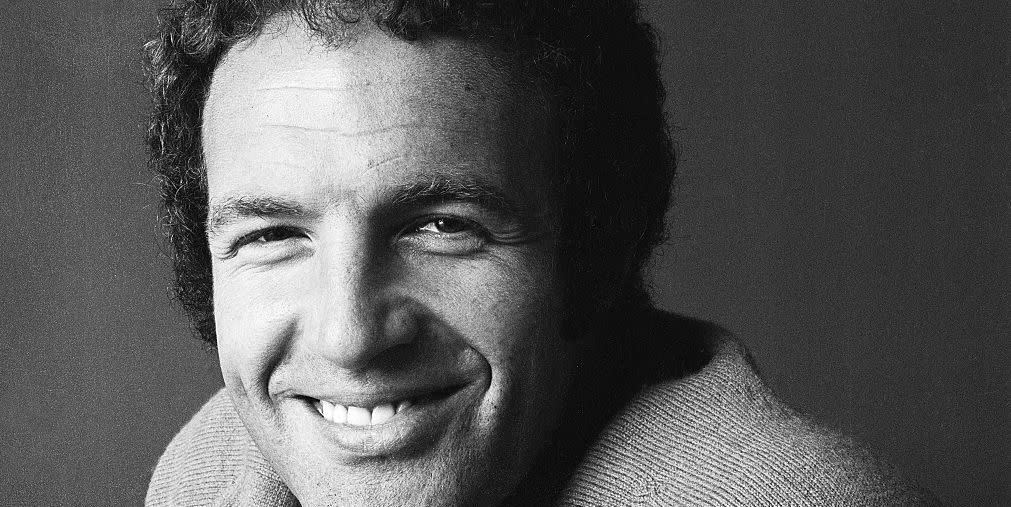

The Watchfulness of James Caan

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It’s all in the nuts. Everybody remembers James Caan’s Sonny in The Godfather as the Corelone family hotshot, the one whose end is as flamboyant as the temper on display when he breaks the cameras of the FBI agents surveilling his sister’s wedding, or when he breaks the face of the wife-beating mook she married. But watch Caan in the short scene with Robert Duvall’s Tom Hagen and Marlon Brando’s Don Corleone as they discuss whether the Family should move into the heroin business. Sonny, in his shirtsleeves and loosened tie, sits on the family sofa listening to the consigliere’s argument for selling dope. He’s got a handful of something—walnuts, peanuts—and as he’s listening, he’s flicking through the bits of shell to find the meat that’s still left. When it’s time for the Don’s answer, Caan sits up, brushes his palms up and down to clean them off, scooches forward on the couch, and waits for his father’s response. He’s like a kid who understands that the time has come to listen. And in the following scene, when he speaks out of turn during a meeting with the hood who wants to bring the family into the narcotics business, he gets, from his father, the kind of reprimand you give an errant child, no matter that this is a grown man. Sonny takes it without a word of protest and walks off, his resentment fighting it out with his embarrassment.

Of all the cast of The Godfather films—Brando, Pacino, De Niro, Duvall, Cazale—Caan, who died today at 82, is perhaps regarded as the most conventional, not associated with the Method the way those other actors are. And yet there’s an interiority to Caan’s work that makes watching him an exercise in suspense.

It’s often said that he played short-tempered men. But by the time the explosion comes in a Caan performance, the fuse has been burning a long time. Think of the moment in The Godfather when he discovers his sister Connie (Talia Shire) beaten by her husband Carlo (Gianni Russo). Sonny wants to know where Carlo is and Connie is scared to tell him because she knows Sonny is going to beat the hell out of him. And Caan does something remarkable. He cuts back his anger, he kisses Connie tenderly on the forehead, and tells her he just wants to talk to him. That’s all. Just talk. You can see it’s bullshit. You know Carlo is a marked man, and yet that moment of false calm Caan affects ties up our guts in knots because we know this tamping down is going to result in an even bigger outburst of rage. And at the end of the following scene, when he looks down on the bleeding, immobile Carlo and says, “You touch my sister again, I’ll kill ya,” there’s no exaggeration in the words. It’s simultaneously one of the most violent and one of the coldest moments in the movie.

Caan does something similar playing a Buffalo tire-factory worker in the 1980 Hide in Plain Sight, the only movie he ever directed. Caan isn’t playing a thief or a hitman or a gangster here. He’s a blue-collar guy who’s played by the rules, doesn’t understand the counterculture rebellion going on in the country (the movie is set in the late ‘60s), and can’t understand why his government won’t help him find his kids when they disappear into witness protection with his wife and her hood second husband. The role may be the most straight-up good guy Caan ever played. And yet he’s the most wound-up average Joe you could imagine. Those tight curls on top of his head were an external manifestation of his inner state. When his new mother-in-law isn’t quick enough to accept the charges on a collect call that will tell Caan where his kids are hiding, you sense that same surge of anger—and then you see him choking it back as he works to get the information he needs

Had Caan been nothing but a fireball on screen he would have been monotonous to watch. What you see in Caan, what most closely links him to the Method approach of the actors he often worked with, is his watchfulness. He doesn’t anticipate. He’s quite winning in his scenes with Jill Eikenberry as the elementary school teacher he begins courting in Hide in Plain Sight. There’s a lovely moment when she tells Caan she’s pregnant and he immediately proposes marriage. You can tell he’s surprised but there’s no reluctance in linking his life up with hers. His realization that this is what he wants to do is right on the heels of his knowing it’s the right thing to do.

And yet his antennae are fully alert when trouble is coming. When he and Tuesday Weld have an interview to adopt a child in the 1981 Thief, and Caan realizes that the pompous social worker conducting the inquiry is about to discover he’s an ex-con, the defensiveness ratchets up by the second. The scene isn’t shaped to be particularly sympathetic towards the social worker, who’s just doing her job. But in drama, fairness is almost always a negative. When Caan lays out what abiding by the criterion of the system means—more kids without a home; potentially good parents eliminated because of one mistake—you’re fully on his side. He shames the officials by linking his and Weld’s “undesirable” status to what he knows is the undesirable status of the kids who will never be adopted and it’s Caan’s unreasonableness that feels like the only recognizably human reaction.

One of my favorite Caan performances, in one of my favorite of all his films, is in a picture he didn’t like much, Sam Peckinpah’s 1975 The Killer Elite. Not many others liked it either. In a famous essay Pauline Kael made the case that the film was Peckinpah’s metaphor for not losing your soul when dealing with the epicene and impersonal corporate world. Caan is an operative for a shadowy CIA-like company, set up and left crippled by his partner (Robert Duvall). His invalid status suits the company just fine, as Caan is too much of an individualist to please them. The movie is about his rehabilitation and his revenge. It’s about what it means to choose to be a subject rather than an object in what Kael called “an involuted, corkscrew vision of a tight, modern world.” The humanity here lies in the cynical squint in Caan’s eye; in his immediate rejection of anything that smacks of bullshit; in the playful way when, half stoned on tranquilizers, he uses his nurse’s stethoscope to croon her a ‘30s ballad; in the unspoken respect respect he has for the skill of the team he assembles, Burt Young as his wheelman and the recently departed Bo Svenson as the gunman no one will work with. (Caan pays Svenson one of the great wacko compliments in movies when he says to him, “You’re not a psycho, Miller. You’re the patron poet of the manic depressives.”) This is one of those times when presence is performance and when you feel as if you are experiencing the movie through the protagonist’s skin.

James Caan was a puzzle. Despite making a splash in The Godfather, he was too regular to keep on playing goombah-hood roles. And yet he was too intense to ever be casual on screen. You could never imagine him in a romantic comedy. But when it came to professing naked need—as he does in a knockout ten-minute diner scene with Tuesday Weld in Thief, two actors, masters at being fully in the moment in front of the camera, getting a chance to act without interruption—he delivered.

But tonight I’m thinking of a performance with a youthful and unexpected lightness, in Howard Hawks’ 1966 El Dorado as the young gunman—and lousy shot—seeking to avenge the murder of the man who raised him. Caan, sleek in a jaunty black flat-topped hat and black-leather shirt, is playing the stock role of the inexperienced youngster who gets in the way but gradually learns competence and maturity from his elders, who here are John Wayne and Robert Mitchum. He even has to grow into his nickname, Mississippi, so given because his birth name, Alan Bourdillion Trahearne, is what you’d expect on a bespectacled Easterner who’s just stepped off the coach. (The name so amazes both Wayne and Mitchum they can barely get it out.) It’s a charming performance and yet Caan is in some ways the movie’s Angel of Death. El Dorado was, until Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, the leading American Western elegy for old men and death. The movie insists on the physical infirmities and indignities of its two stars and through it all, often in black, strides the young Caan, reciting the poem his mentor taught him, Poe’s “El Dorado,” with the young wandering knight who meets “a pilgrim shadow.” Knight was too fancy a description for Caan. It doesn’t take into his account his humor, his sexiness, his volatility. And those are not bad things to have achieved when it’s time to go “down the valley of the shadow.”

You Might Also Like