This tech could secure voting machines, but not before 2020

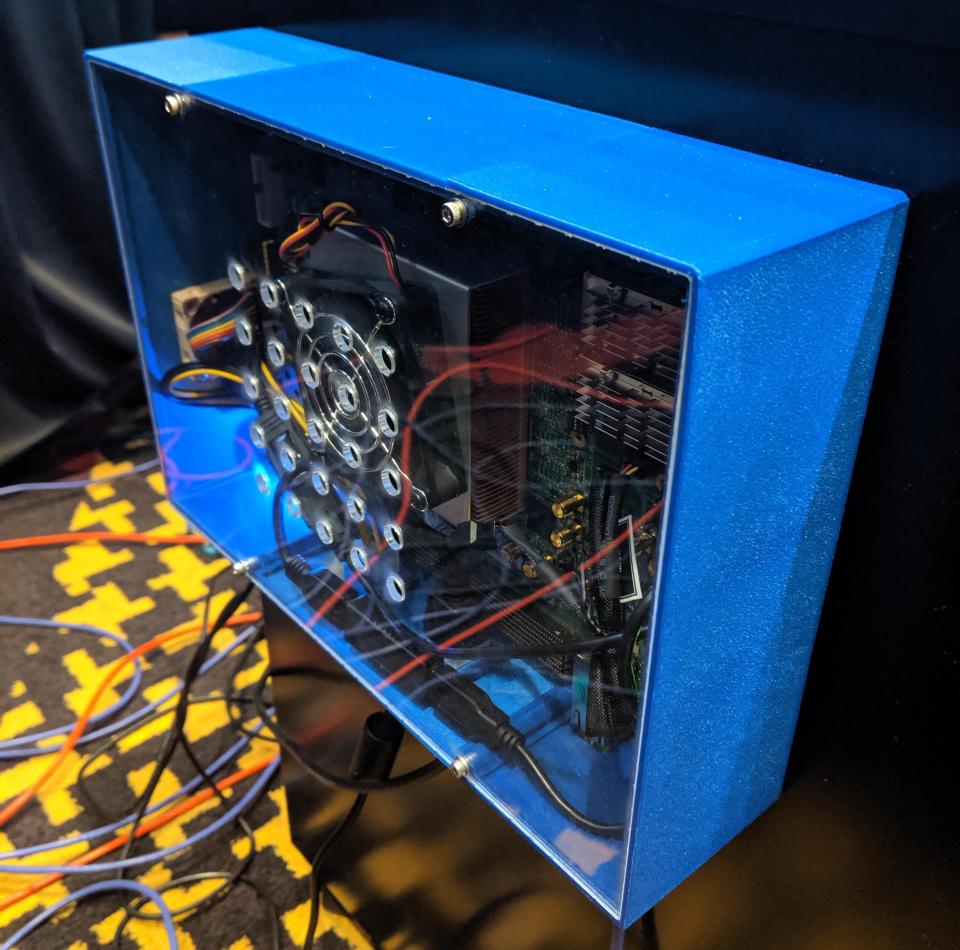

LAS VEGAS—A blue box on display here at the DEF CON security conference could make voting machines much more secure—and the circuitry inside might do the same for consumer gadgets.

But the technology demonstrated by the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and Portland, Ore-based Galois won’t be ready in time to secure voting machines in the 2020.

Still, when it does hit the market, the tech could help put a stop to some of the more common cyber attacks on your connected devices.

Tap here to vote

The voting experience of the DARPA/Galois hardware at the Voting Village exhibit might not seem different from that of the obsolete voting machines lined up for inspection nearby.

You choose answers to such questions as “Favorite Star Wars Movie” and “Correct Pronunciation of GIF” on a touchscreen, a paper prints out with your choices and a QR code storing them, and you feed that into a scanner.

But the circuit board inside a blue frame attached to that scanner incorporates the work of DARPA’s System Security Integration Through Hardware and Firmware project—SSITH for short.

“Yes, we did kind of make that fit inside the acronym,” program manager Linton Salmon said of the Star Wars reference during a talk Friday.

SSITH aims to build processors on open-source architectures that resist most common hacking techniques at the hardware level, if at some cost in performance.

“Most of the manufacturers of processors over the last 15 to 20 years have been primarily concerned with performance and power,” said Galois researcher Dan Zimmerman in an interview Saturday. One objective of this project is to quantify the cost of this added security in those areas.

Next year at DEF CON, this team hopes to see five different polling-place demos built on this design. But it would fall to other parties to ship voting hardware—as Salmon emphasized in an interview Saturday, “The SSITH program is not about voting results and security.”

That’s because their ambitions exceed elections. Processors that shrug off such common tactics as buffer overflows (in which an attacker shoves excess data into an input field, causing a crash that opens memory in which hostile code can run) would help in areas from connected appliances to supercomputers.

Our long national hangover continues

We’re having this conversation about safer electronic voting hardware because of an overreaction almost 20 years ago to usability problems with old-school ballots that erupted in the 2000 election and its travails with punch-card ballots.

The quickly-passed Help America Vote Act mandated replacing old, analog voting machines with newer and smarter models. Vendors met that demand with a round of devices built on general-purpose Windows platforms at a time when Microsoft (MSFT) was much more innocent about network threats.

“Almost everything produced to comply with the Help America Vote Act has had terrible security vulnerabilities,” said Voting Village co-founder and Georgetown University law and computer science professor Matt Blaze in a talk Friday. “We took a problem that was hard, and we added software to it.”

For example, the Winvote machines I voted on in Virginia for years offered so many vulnerabilities that any red-blooded, purple-haired DEF CON hacker would laugh at the challenge of exploiting one.

Those machines have long since been retired, but others still in service in 14 states suffer the same architectural defects of recording votes without a paper ballot first seen by the voter—meaning you must take the computer’s word for it. Newer proposals to collect ballots on blockchains also leave no analog records.

While Blaze allowed that DARPA’s work could open useful possibilities, he said it was more important to move to systems that record votes on paper—and then verify each count with a quick “risk-limiting” audit.

What we can do now

Interest in Vegas in better election security has yet to be matched in parts of Washington, where Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) has blocked votes on Democratic-supported bills to mandate more secure voting systems.

"Why hasn't Congress fixed the problem? Two words: Mitch McConnell,” roared Sen. Ron Wyden (D.-Ore.) in a talk Friday. “I sure wish he had been walking around with me in the Voting Village, seeing a who's who of hackable voting machines.”

Wyden also cast blame on the voting-machine lobby for flexing its “very big political biceps” to lock in contracts from states for “a new generation of overpriced, unnecessary technology.”

But Wyden’s suggested remedy—that everybody at DEF CON tweet their support for election-security legislation—seems unlikely to move the immovable Kentuckian. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D.-Mass.) and presidential candidate does have a plan for this, announced in late June, but McConnell could easily still be around to block that.

If you live in a state that’s adopted voting-security initiatives on its own—perhaps Nevada, whose deputy secretary for elections Wayne Thorley said in a talk Saturday that “the 2020 election will be much more secure than the 2016 election”--that could be fine.

Otherwise, you may have to hope the dice keep landing in your favor.

Email Rob at rob@robpegoraro.com; follow him on Twitter at @robpegoraro.