Viggo Mortensen on Falling and the Time He Was Found in the Woods as a Baby

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“As a baby, I crawled out of the crib twice, and they had to look for me,” Viggo Mortensen tells me. “Found me with a dog one time in the woods.”

If you were to ask me which actor was most likely, as a baby, to have been found wandering in the woods with a strange dog, Mortensen would be at the top of the list. Throughout his career, before and since his breakout as Aragorn in The Lord of the Rings, Mortensen has cultivated an aura of quiet eccentricity about him, bolstered by the various facts of his life: He lives abroad in Spain, runs his own independent publishing company, writes poetry, unceremoniously appears fully nude onscreen, and, at least until 2016, used a flip phone.

When Mortensen and I speak in January—our conversation takes place over Zoom and email—he’s in his Madrid home, a stack of books and a rainbow peace flag visible in the background. He does not talk in sentences so much as winding, soft-spoken paragraphs, which sometimes meander into anecdotes involving being discovered hanging out with animals in the forest. Since the pandemic began, he’s been occupying himself by reading, completing two new screenplays—“One is a love story combined with a story of vengeance. The other is a story about a 10-year-old girl's evolving view of her home environment in wartime”—and promoting his directorial debut, Falling.

Falling, which premieres in the U.S. on February 5, tells the story of a father and son struggling to relate to each other during the twilight of the elder’s life. Willis (Lance Henriksen) is a severe, conservative elderly farmer from upstate New York declining from dementia; his son, John (Mortensen), is a gay man who brings his father out to California to care for him. The present storyline is interspersed with scenes from their painful past together.

Mortensen began writing Falling on the plane ride back from his mother’s funeral in 2015. He found himself thinking about all the different stories he heard about her from friends and relatives and figured they would make a fine short story.

“A few days after getting home, I thought, Well, I'll just read this through. I thought it might not be that good,” he recalls. “It's like the middle of the night, you wake up, you have an idea, and you write it down. You think, Oh, that was really great, what I wrote down last night. Then you read it, and it's usually, Hmmm. But I read this and I thought, No, this is actually pretty interesting.”

GQ: There are many parallels to your life in Falling. Your father also died from dementia. You grew up in that same tough northern New York landscape as your character. Was incorporating those autobiographical elements cathartic for you?

Viggo Mortensen: There’s that time when, let's say you love your mother—which I did and do—and she dies, everything's very present. Then they sort of fade or you adjust to life without that person being alive anymore, and you find a way to move on even if you often think of her. But that didn't happen with me, because I wrote a movie about it.

There's been a lot of dementia in my family. My stepfather, three of my four grandparents, aunts, uncles. I've seen it up close. That was something I wanted to explore, but by exploring that, it kept these things alive. In a way, it was like not allowing a wound to close, but not in a negative way. I found it productive.

The fact that so much of your family had dementia, and it’s passed on genetically—has that knowledge changed the way you live your life?

I was telling a friend of mine about this: “I guess it's only a matter of time before I get it.” They said, “Well, not necessarily. There is a blood test, and they can see if you have a genetic predisposition to getting dementia or Alzheimer's." I said, "Really? Did you do that?" He goes, "No, no, no. I don't want to know." I said, "Well, I do." So I went and I got the test, and the result was—who knows if it's reliable or not—“No, it doesn't look like you have any predisposition.”

MCDFALL ON003

Well, that’s some good news.

Who knows? Life is unpredictable, as we've seen this past year, certainly.

It's something that I've learned a lot from. In any relationship, you have to be flexible. If you really are friends with someone, you on some level are trying to serve them. With dementia, obviously, it's even more important. When they start saying things that are really strange—like, say they start telling you that they just had lunch with someone that you know died 30, 40 years ago, your impulse is to say, "No, Mom, they're not here anymore.” But that's actually exactly the wrong thing to do, because that person dies for them again, and it is very upsetting. So you learn to say things like, "Well, what did you guys have for lunch?" You have to ask yourself, who are you helping by correcting them? It's you who wants them to see the present the way you do. If we say that memory is subjective, then why is the present of someone who sees something completely different and feels something different any less valid than yours?

One topic that this movie explores in depth is masculinity and the way it's traditionally performed and how that can be at odds with how newer generations interpret it. What was the signaling you received around masculinity growing up, and how did you work to subvert that as you got older?

My dad was typical of his generation. He was raised on a farm. He ran away from home when he was 14 and just went to live and work on another farm. He was kind of rebellious and stubborn, but he was typical of that generation that was born during the Great Depression and went through World War II. Typically they were authoritarian in a way. Even if they were kind, the father was the breadwinner, they don't adapt to other people, they have the final say on things. I looked up to him. He showed me how to go fishing and camping and all these things outdoors. I learned to ride horses when I was very little. What was typical modeling for a heterosexual boy, I guess. Then, in the ’60s and the ’70s, things started to open up. My dad didn't really adapt very well to the changes.

My parents divorced when I was 11, and when that happens, you take one person's side, then the other. It takes a while before you get the whole story. Because my father wasn't there, my father was idealized for a few years. Absence makes the heart grow fonder and so forth, but looking back, he didn't come to see us that often. That made me probably even more independent. That was sort of the model: being adventurous, being bold.

How did becoming a father influence your relationship with your father? And conversely, how did your relationship with your father influence your relationship with your son?

Well, the other thing I would say is typical of that generation is, because they were breadwinners and out of the house, you didn't see them that much. I wanted to do it a little bit differently. I was much more involved with everything from when Henry was born. The main thing I wanted was to have better communication with him. Like, "Let's talk it through. If you don't want to do it, I'll explain why you can't, and I'm sorry if you're disappointed, but that's the way it is." Or be open to maybe changing my mind if he came up with a good reason. There’s a dialogue.

As far as the way it affected my relationship with my father was—which often happens and you even see it in Falling—fathers who have been very tough, with their grandchildren they can suddenly become doting. It's almost like subconsciously they're realizing, “I have another crack at it.”

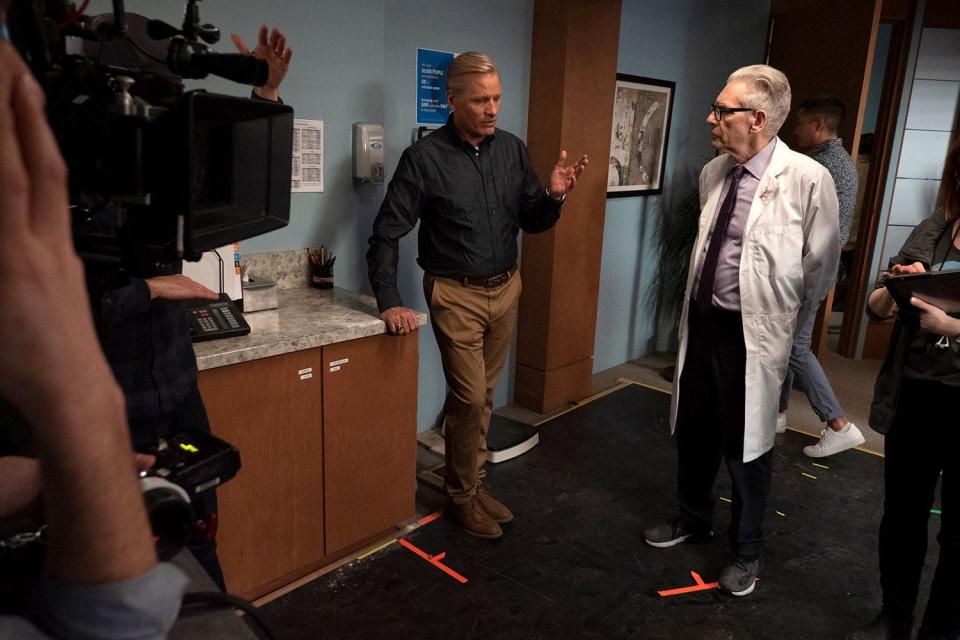

David Cronenberg has a small part in Falling, as Willis’s proctologist. What was it like to direct him versus the other way around?

He was perfect. He was funny. It was a good experience. I didn't feel any more nervous directing him than anyone else. Because we’re friends, I didn’t feel a certain pressure. Although it was interesting, because we were shooting in his hometown of Toronto that day. So for the crew it was like, "Ooooh,” this frisson, when he came on the set.

I had no idea at the time that Lance Henriksen didn't know who [Cronenberg] was. I remember on the day, Lance said, "He's very methodical. Very specific. Pretty good. It's kind of scary." Two months ago he calls me: "I just saw this thing on YouTube, this Q&A with you and Dr. Klausner. What the hell? That's Cronenberg!" I go, "Yeah. You didn't know that was David Cronenberg when we were shooting?" He said, "No, I had no idea." That was funny.

Are you two in talks for another collaboration sometime soon?

Yes, we do have something in mind. It's something he wrote a long time ago, and he never got it made. Now he's refined it, and he wants to shoot it. Hopefully, it'll be this summer we'll be filming. I would say, without giving the story away, he's going maybe a little bit back to his origins.

So, body-horror type stuff?

Yeah, it's very interesting. It's almost like a strange film noir story. It's disturbing and it's good, I think. But since his origins, he's obviously developed in terms of technique and self-assurance as a director.

The bathhouse fight scene in Eastern Promises is one of the most iconic and visceral in movie history. Can you share any notable memories of filming it?

Shooting that scene was sometimes physically painful and uncomfortable, but also an exciting choreographic exercise for everyone involved. Considering the complexity of the sequence and the space we were working in, David and his team filmed it very efficiently. We did some additional filming the morning after, though—details and close-ups—and it took longer to cover all the new welts and bruises than it did to apply the various tattoos that my character sported.

There's going to be an Eastern Promises sequel, but neither of you ended up being involved. How did that end up shaking out?

Is there going to be one?

The details are still vague, but it seems that Jason Statham is involved.

Yeah, it didn't work out. I don't know. I can't speak for David. I think it was mostly a timing thing. Well, I hope they get it made, and I hope it turns out to be a good movie.

Are you planning to watch the Lord of the Rings remake on Amazon later this year?

Yeah, directed by a Spanish director, [J. A.] Bayona. Yeah, I'm interested to see what they do. They've been shooting that in New Zealand. Bayona is a good director, so it'll probably be worth watching. I'll be curious to see what they do, how they interpret Tolkien. I don't know how much the Tolkien estate has allowed them to use.

After Lord of the Rings came out, you were vocal about your anti–Iraq War stance and would publicly wear “No Blood for Oil” T-shirts. And you got a lot of flak from the right wing for that. Then, in 2016, when you said you voted for Jill Stein, you had liberals turn on you. Has it been surreal to get criticism from both sides of the aisle?

No, it's just life. If you're sort of in the public eye, people have opinions about you, whether you like it or not. I think the times we're living in, it's hard to speak about anything without some flurry of activity happening, because people just like to get attention for saying things about other people, whether they're true or not. That just happens.

You’re based in Madrid, and, as you mentioned, Spain has been doing much better than the U.S. in handling the coronavirus. Beyond that, I sense the quality of life is better in other ways. Do you think you’ll ever move back to the States, and why or why not?

Normally, I spend much of the year in the U.S. and in other places outside Spain, but, owing to COVID-related complications, travel has lately been difficult and, in some cases, illegal, except in truly extraordinary circumstances. I have tried to be mindful of the necessary restrictions advised or stipulated by relevant authorities. Sometimes a person yearns to flee their country out of fear, necessity, or even political convictions, but I am a citizen and longtime resident of the United States and am attached to its landscapes, history, and people.

I'm not partial to the idea that any country or government is exceptional, and I believe that we all have the potential to feel at home anywhere and in any society, as all places and peoples have inherent value. As the philosopher Bertrand Russell said: "No nation was ever so virtuous as each believes itself, and none was ever so wicked as each believes the other."

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Originally Appeared on GQ