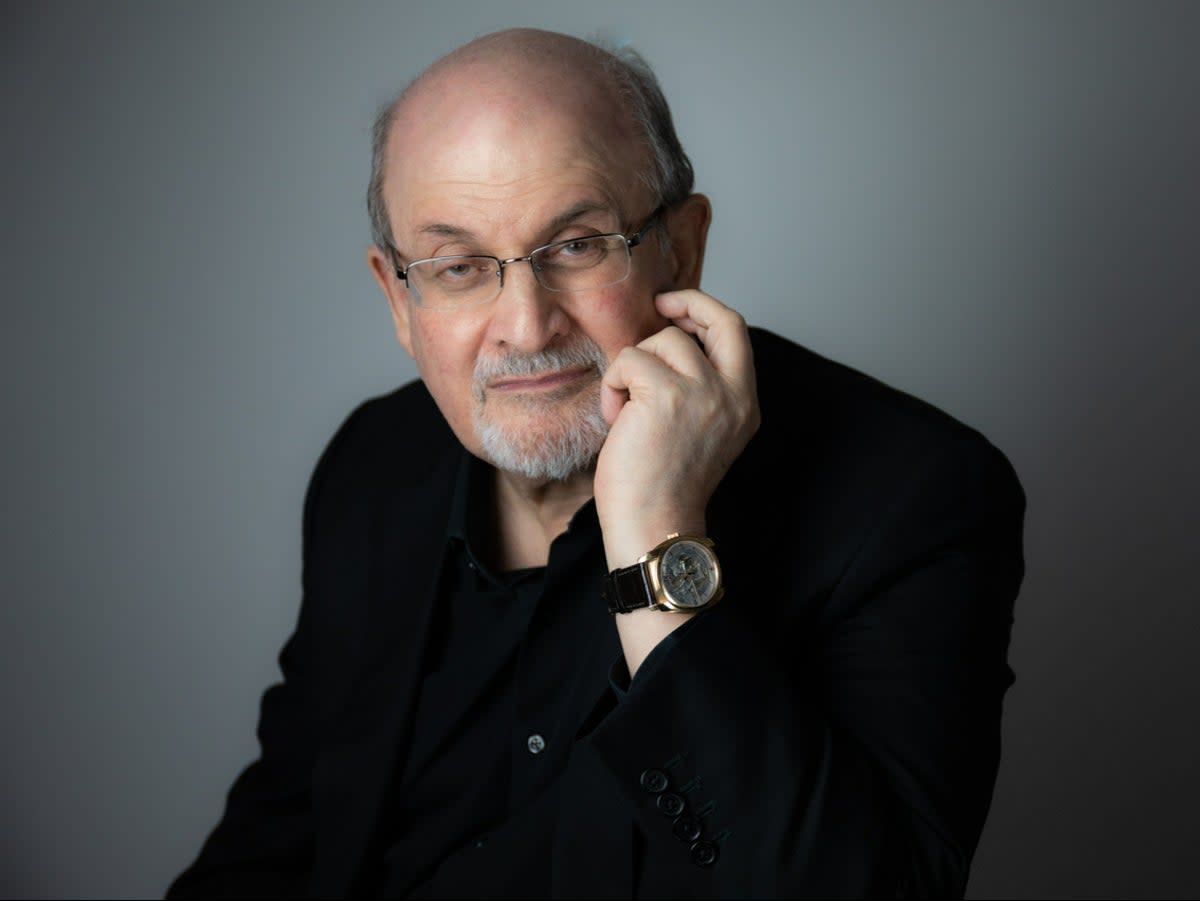

Victory City by Salman Rushdie review: Stories outlast tyrants in this vibrant, sweeping tale

Some of the battle scenes and violence in Victory City, the epic new novel by Salman Rushdie, may induce a wince or two – especially graphic descriptions such as “the cannibal pungency of women being cooked alive”. Rushdie wrote these words before suffering that horrific attack at the Chautauqua Institution in New York in August 2022, when the 75-year-old author, who received death threats from Iran in the 1980s after his novel The Satanic Verses was published, was stabbed 15 times, causing him to lose the sight in one eye and the use of one hand.

Rushdie’s courage and steadfast belief in free speech continue to be a source of inspiration and his exuberant writing remains a source of pleasure. Victory City, an ersatz translation of an ancient Indian epic, deals with the aftermath of a battle between two kingdoms in 14th-century southern India.

The story, partly written during a lockdown in which Rushdie suffered a serious case of Covid, follows nine-year-old Pampa Kampana. After witnessing the death of her mother, she becomes a vessel for her namesake, the goddess Pampa, who begins to speak out of the girl’s mouth. Pampa Kampana, who “carries the scent of her mother’s burning flesh in her nostrils for the rest of her life”, plays the essential role in the rise of Bisnaga – “Victory City” – a new wonder of the world.

Rushdie, author of the Booker-winning Midnight’s Children, has long wrestled with arguments about reason and religion, creating nuanced stories in a world where complicated answers are not always welcome. The rise of the titular city allows Rushdie in this, his 15th novel and his first book since 2021 essay collection Languages of Truth, to explore the question of origins. With his deceptively drowsy satirical wit, he has fun with the way Pampa initiates human interaction in the city by creating the fiction of castes and faiths. Rushdie seems to be suggesting that in the grand narratives of power structures, the historical amnesia imposed on subjects is a vital ingredient. “Everything lands me in trouble,” Rushdie said a few years ago and no doubt his latest novel will enrage his zealot critics.

And Rushdie is drawing parallels to the modern world, of course – the rise, decline and fall of kingdoms; the caustic view of empire building – in a fictional tale about the fleeting nature of power and control. This impermanence is clear in the relationship between Bukka and Hukka Sangama, the two brothers Pampa entrusts with planting the magic seeds from which Victory City sprouts. They initially battle verbally for supremacy, before Hakka is pronounced king. Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun, empire-builder Chairman Mao famously declared. In Rushdie’s Victory City, power grows out of the tip of a sword. The stench of death is never far away in this book.

Victory City has been hailed as a “feminist” novel, mainly because of the redoubtable Pampa, the beautiful daughter of a well-loved potter, who will not accept that there is any such thing as women’s work, nor that she should succumb to her fate and “sacrifice her body merely to follow dead men into the afterworld”.

Rushdie makes his own salient point about sexual abuse in the way young Pampa is exploited by the “supposedly abstinent scholar” Vidyasagar, a devout older man who “did what he did” to Pampa while they shared a cave. He molests Pampa without even knowing her name, while presenting himself to the world as a man “lost in meditation, studying the wisdom of sacred texts”.

The novel is certainly evocative: the smells and tastes of cumin, cloves, turmeric and big cardamoms, the actions of elephant keepers, monkey handlers and tradesmen fill the pages of a novel that keeps asking: what is the nature of history and what is a human life?

I guess that to wholeheartedly enjoy Victory City, you will need to be a fan of tales involving magic realism, mythology and supernatural visions. Rushdie’s imagination certainly seems pleasurably fired by returning to an Indian novel after a decade of Western-based novels, and although the fantasy of Victory City will not be to everyone’s taste (and there are flaws, including some pedestrian similes), it is a vibrant, sweeping tale with a valuable message: that stories outlast tyrants and words can be the true victory.

‘Victory City’ by Salman Rushdie is published by Jonathan Cape on 9 February, £18.99