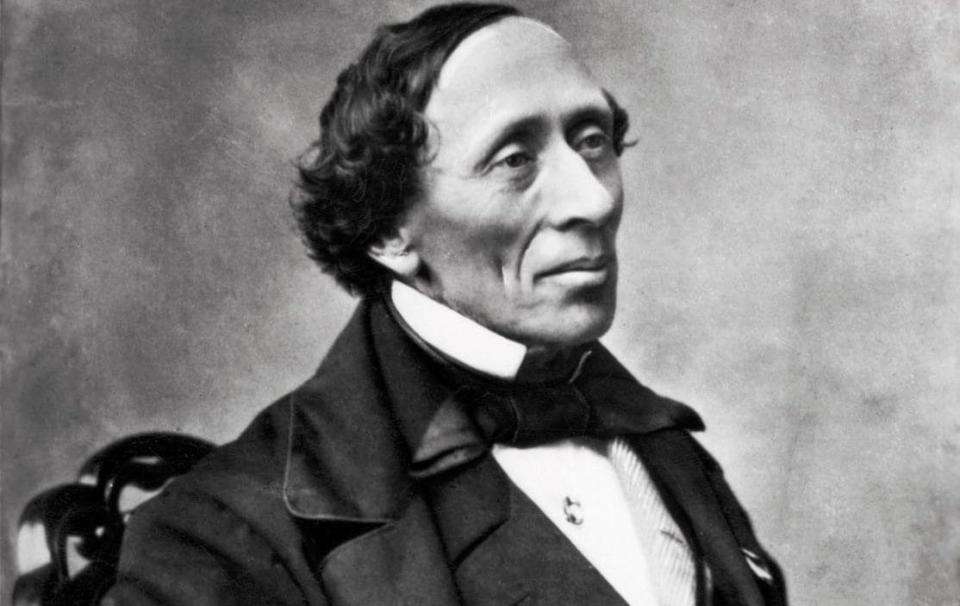

Vain, miserable and sexually frustrated - the truth about Hans Christian Andersen

The little mermaid pining for the love of an unattainable mortal; the destitute match girl dying outside in the snow; the ugly duckling unaware that it’s destined to be a swan; red shoes that dance away on their own; the emperor’s non-existent new clothes – Hans Christian Andersen’s imaginings are deeply embedded in our culture, their influence percolating as far as the modern fantasies of Toy Story, His Dark Materials, Frozen and even the poor man who chances his luck at the centre of Netflix’s hit show, Squid Game.

But despite all their familiarity and the sugar-coated Disneyish adaptations, their resonances remain dark and complex. Not quite allegories, parables, fables or fairy-tales, but absorbing elements of all of them, they are a prime source for the genre of children’s literature that extends from Alice in Wonderland to Harry Potter, offering haunting metaphors for the human condition that reflect crises and torments in Andersen’s own life.

The latest of his tales to be adapted for the stage is the lesser-known The Fir Tree, which will play at Shakespeare’s Globe this Christmas. “If only” is its theme: like The Little Mermaid, it is a tragedy of wasting one’s limited existence in yearning for what you haven’t got or can’t have – the portrait, as Andersen’s biographer Jackie Wullschlager puts it, of “a certain psychological type who, as Andersen was, is unable to be happy in the moment because he is always longing for greater glory.”

Andersen was turning 40 as he wrote it in 1844, and was at the peak of his celebrity and success. But his journey to this point had been long and turbulent.

After a dirt-poor and troubled childhood in a remote Danish village – his mother died an alcoholic – he had escaped to Copenhagen, where he’d attracted notice as a boy singer and dancer. A patron had awarded him, at the belated age of 18, a grammar-school education that gave him the skills to embark on a career as an author (he would also produce more conventional novels, little read today). The tales he began writing at the age of 20 in 1835, influenced by the authentic folk material collected by the Brothers Grimm, soon made him as famous as Dickens throughout the western world.

But he took scant interest in the political and social revolutions of the Victorian era: a crashing snob, his friends were entirely drawn from the élite of the titled, wealthy and famous. They were also exclusively adult: unlike his younger contemporary Lewis Carroll, Andersen wasn’t particularly sympathetic to children, and his stories aren’t altogether addressed to them.

“Not until they are grown up can children see and grasp their full significance. The naïve was only part of my talent,” he wrote in his diary, and he was right; his fictions can be read and interpreted on so many different levels.

He wasn’t a very nice man. Vain, hypersensitive, paranoid and variously phobic, he was neurotically restless and travelled ceaselessly, even though he repeatedly returned to his Danish roots. Sexually, he was tormented by infatuations with both women and men, yet appears to have died a virgin. What drove him, however, was a blazing conviction of genius that allowed his tangle of internal confusions and aspirations to coalesce into some of the greatest and most original literature of his era.

As an artist, he worried that his public wanted him to repeat himself; privately, he was torn between feelings for Jenny Lind, the sensational “Swedish Nightingale” soprano, whose rags-to-riches progress echoed his own, and Carl Alexander, the earnest young Grand Duke of Weimar.

The Fir Tree marks a point in Andersen’s life at which his mood darkened into pessimism. A fir tree wants to be taller than its neighbours in the forest, it wants to be a bird and fly off to see the sea, it wants to be taken into a happy home and decorated for Christmas. It remains either regretful of the past or dreaming of something better, somewhere else, until it ends up being chopped up and burnt. Despite its comic detail and superficial fireside charm, its message is unmistakable: a life not lived in the present is a life wasted.

Playwright Hannah Khalil has adapted The Fir Tree for the Globe’s production, to be directed by Michelle Terry, and in keeping with the spirit of the times she will be giving its implications an ecological slant. The theatre’s open-roofed yard will be filled with a forest of real trees, and puppets made out of Amazon boxes by the cardboard wizard Samuel Wilde will serve as the non-human characters, with audiences encouraged to add their own recycled contributions.

“We want there to be theatrical magic,” says Khalil. “But we also want to convey a sense of nature existing for nature’s sake, not just for us.”

The bleak, almost cynical ending of Andersen’s original text will be softened. In Khalil’s reading, it becomes “a coming-of-age story about wanting to know what’s coming in the future but learning to live in the moment.” At the Globe, the fir tree itself “may or may not” end up being cut-up and burnt – a child actor will have the power to change the ending. Khalil’s play will also incorporate elements of Andersen’s earlier tale, The Nightingale, in which the song of a bird living in a wood and singing spontaneously trumps the artifice of something elaborately constructed to mimic it.

Marking a time when Andersen’s infatuation with Jenny Lind and the spell of her singing was at its peak, The Nightingale asserts the victory of the genuine creative artist over imitators and fakes. Yet after writing The Fir Tree, Andersen lost all faith in his achievement – one of his last stories, Auntie Toothache, concludes with the despairing thought that, “Everything ends up in the bin … wrapping paper for salted herring’’. At least the enduring fame of his own writing has proved him wrong.

The Fir Tree is at Shakepeare’s Globe, London SE1, December 20-30. For tickets: 020 7401 9919; shakespearesglobe.com