This Is Us Star Milana Vayntrub Shares Her Refugee Story

This Is Us actress Milana Vayntrub has recently been featured in a Lives of Women video comparing her refugee story to what’s happening in the Syrian refugee crisis today. Lives of Women is a digital portrait series created by Indigenous Media that produces short videos showcasing women's deeply personal experiences. Below, Vayntrub shares her thoughts on the crisis and what can be done to help.

Big hair, acid wash jeans, Baby dirty dancing with Johnny... Oh, the ’80s! A time when Americans were cool with Bill Cosby and viewed the world through neon-colored Wayfarer glasses.

For my family, however, it was an entirely different reality. In the ’80s, we were living in the USSR where anti-Semitism was a deeply ingrained part of the culture. Being a Jewish person in the Soviet Union was not easy. Not that I remember any of that, I was barely old enough to chew back then, but for my parents, both Uzbekistan-born Jews, life was a struggle.

RELATED: It's Not About Bathrooms: Laverne Cox on the Attack Against Trans Rights

There were no jazzercise classes or Nintendo marathons for them. My mom and dad couldn’t get work, which means they couldn’t pay bills, which meant figuring out how the hell fat baby Milana was supposed to eat. Although they built a close, loving community in their neighborhood, they were harassed on the streets and made to feel like outsiders in their own country.

In the late ’80s, the USSR loosened its restrictions on immigration. When the government was like, “Y’all wanna bounce?” my family, along with tens of thousands of other Jews ran for the door, in an attempt to make a better life in America.

At the time, Jewish emigration from the Soviet Union was a long and complicated process. My family had to live in Vienna for three months, then in Italy for another nine, while we waited for refugee status. The US Deputy Secretary of State, described the situation as ''intolerable and inhumane,” according to The New York Times, but my parents sucked it up. They took odd jobs, crammed into expensive apartments with other families, and longingly side-eyed locals sipping their espressos until we were granted the green light to come to America.

Milana and her mother in Italy

In August of 1989, we arrived in Los Angeles where we had family. With their help, along with that of Jewish resettlement organizations like HIAS, my parents were set up with jobs. My mom worked in a factory that manufactured airplane parts and cleaned medical buildings at night, all while completing a program offered by the Jewish Federation to become a registered nurse at Cedars-Sinai Hospital. And my dad, he worked as a donut deliveryman—they could finally bring home money and donuts for our family, what more could a fat kid like me ask for?

My parents worked their asses off to afford private school, summer camp, and gymnastics classes (which I’m pretty sure is a prerequisite for all Russian kids) so that I could take part in everything this promised land had to offer.

Despite all their love and hard work, as a kid, I remember feeling as though I couldn’t culturally catch up to my peers. Especially when it came to beach towels—these really stupid, but really cool, but actually really stupid towels. All my classmates owned these colorful beach towels with Disney characters on them. I desperately wanted one, but instead, I had this orange and white patterned thing, a glorified Slavic doily—that my parents brought with them from Uzbekistan. To me, it was a smoke signal alerting all potential friends that I was NOT. FROM. HERE. Like, here is this thing that I’m going to lay out that lets everyone know my family is different. I am an “other.” I can say that with levity now because I know how ridiculous it sounds, but oy, I really let that damn doily embarrass me.

Towels aside, we were lucky. Super lucky. Absurdly lucky! There are, of course, the stories that my parents can recount of their friends being harassed by police and having to deal with cultural tensions, but all in all, our communities welcomed us. Being a white person entering a majority white country is a lot easier than entering as a person of color, or one wearing say, a hijab—that’s a privilege we had that’s important to recognize.

RELATED: Brooklyn Nine-Nine Actress Stephanie Beatriz on Battling Disordered Eating

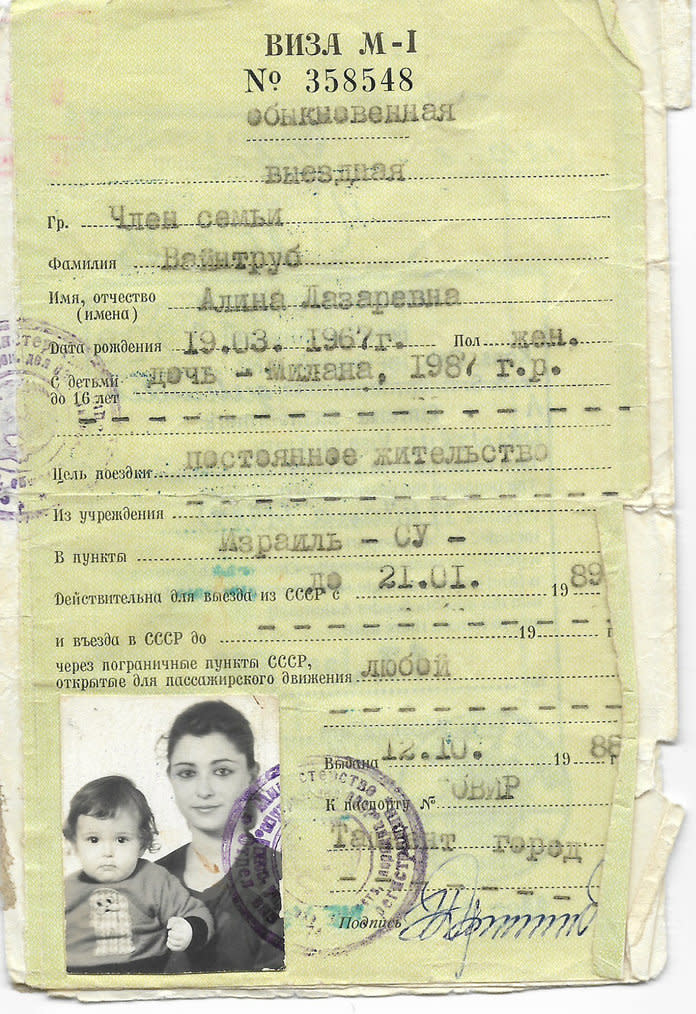

Milana's mother's passport from 1989

Which brings me to 2015… back when man buns were all the rage, SnapChat became a religion, and Cosby was outed as a pervert. It was a wild year in pop culture and it also happened to be the year that I decided to go on vacation in Greece, where I saw firsthand what was going on with the Syrian refugee crisis.

As embarrassing as it is to admit, prior to my trip I was completely unaware of the atrocities of the Syrian war. I had no idea that millions of innocent people were being forced to leave their homes, urgently fleeing their country. It’s not that I’m some idiot that lives in a cave—it’s just that it’s easy for us to curate our news based on our interests. Also, our mainstream news media wasn’t covering the details of the civil war that had erupted between the Syrian government and extremist groups. In my opinion, it still isn’t being discussed as much as it should be.

It was eye opening, to say the least, and once my eyes were open it was impossible to close them. It felt silly to be on vacation. Here were all these humans—mothers, brothers, babies, grandparents—going through a struggle similar, yet far more devastating, than what my family had been through, and I was supposed to go back to taking selfies at the Parthenon? No. No f----ing way.

I extended my trip and went to Lesbos, an hour flight away. It's a Greek island half the size of Rhode Island, where rafts full of refugees were pouring in and volunteers, like me, were standing by to aid them. The people I met had traveled by foot or car to Turkey, where they paid smugglers to take them across the Aegean Sea on tiny, over-cramped rafts. I did everything I could to help, but quickly realized that the biggest influence I could have would be in sharing their stories.

When I got back to the States, I turned to social media for support and made a YouTube video about my experience. I wanted to paint a more human and detailed picture of the crisis that the news, for whatever reason, was not covering. At the end of that video, I listed a website that gave people the opportunity to share their time, money, and voices through an organization I launched called Can’t Do Nothing.

I took to social media to spread the Can’t Do Nothing word, because the truth is if I see a burger, I want a burger. If I see a kitten, I want to pet a kitten. My hope is that if you see someone doing good, you might want to do some good, too. And if we inspire each other, we can create a ripple effect of good.

We are all insanely similar yet vastly different in wonderful ways. And we have to remember that refugees are just as silly, smart, weird, or loving as the next person. They have crushes and heartbreaks, favorite Star Wars characters and pesky allergies, dreams for the future, and, just like us, the right to reach for them.

RELATED: Tony-Winning Actress Sarah Jones on Creating Characters from Her Multiracial Background

Talking about these people and the crisis they are facing is the only way that change is going to happen. By providing attention, respect, and resources to refugees we are giving them the tools to thrive. The more fear we have of this “other,” the more we are isolating them, leaving them feeling desperate, alone, and stranded without any of the basic human requirements for success. I want the world to respond to communities in crisis with love, just like my family was granted.

In the year and a half since I launched Can’t Do Nothing, we’ve been able to make a real, substantial change in the lives of Syrian refugees. Through partnerships with organizations like Carry the Future, Salam UK, and The Syria Fund we’ve sent kids to school, provided prescription eye glasses, bought emergency medical vehicles, and fed thousands of people. But of course, our work is nowhere close to done.

We are standing at a crucial moment in history. Never has it been more important for us to open our eyes and hearts to the world around us. We are all influencers, so let’s recognize that power and use it for good. Sure, 2017 will be known as the year of Trumpland, kitten memes, and Kardashians, but it could also be a time we look back on as an age we rose up to share love, compassion, and support for all the humans on this earth. It’s up to us to make that happen.