‘It’s Like the Unwinnable War’: How the Team Behind Dune Finally Got it Right

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

There is no Dune without sandworms––creatures that have inspired generations of readers, filmmakers, writers, artists, and fans. First introduced in Frank Herbert’s 1965 masterpiece, the immense desert-dwelling sandworm has come to define the beloved sci-fi saga while also bedeviling both fans and filmmakers. But a little over two years ago, undaunted, Cinematographer Greig Fraser was in the Wadi Rum desert in Jordan trying to frame up one of the most iconic images in 20th century science fiction.

“I do remember framing up something and [Director Denis Villeneuve and Special Effects Supervisor Paul Lambert] going, ‘No, you don't have it close. You got to go back 40 meters.’ I'm going, ‘Wow.’ I couldn't believe I was so far out,” Fraser tells me of trying to get the shot perfectly.These things, as Herbert imagined them, are big. Really big. And the same could be said for the scope and monumental task of attempting to adapt Dune into a major studio film. This is, infamously, not the first time it has been attempted.

For the uninitiated: Dune is a massively complex story about noble houses warring over the immensely valuable resource called Spice that is only mined in the sands of the desert planet of Arrakis. Young Paul Atreides is the son of Duke Leto Atreides, who is commanded to take stewardship of Arrakis from the brutal Harkonnens. What’s difficult about adapting this story is not just the book’s long exposition, hundreds of thousands of years of history, galactic politics, languages, and cultures––but the look and feel of the universe that Herbert created in 1965.

In 1974, three years before Star Wars, the great Alejandro Jodorowsky attempted to make a version of Dune with a cast that included Salvador Dalí, Orson Welles, Gloria Swanson, David Carradine, Mick Jagger, and music by Pink Floyd. His film was never made (although there is a great documentary about it: Jodorowsky’s Dune, which is worth watching on its own). And, famously, there’s the ill-fated version made by a young David Lynch in 1984, which despite being a box office flop with a script that breezes over and fumbles the book’s key themes, is still worth viewing as an extremely eighties spectacle. There’s a better, but still clunky, made-for-TV version that aired as a miniseries on SyFy in 2000. Plus a handful of halted projects and abandoned attempts from other producers and directors. All this saddled Dune with a tough reputation: unadaptable.

“This is the unmakeable movie. It's like the unwinnable war,” Fraser says. “Surely it would be like a monstrous endeavor to at least attempt to do this film and to try and do justice to the book that has enthralled generations upon generations of readers.”

What’s different now? Call it bravery or reckless ambition, but this version has Villeneuve, who’s proven his sci-fi chops with Blade Runner 2049 and Arrival (nominated for Best Picture at that year’s Oscars), and saw making Dune the “right” way as a lifelong ambition.

“I must say making a film like Dune, which did scare me in the first instance, seemed possible because of Denis, by his stewardship of the film and his sort of determination to make sure the film was the very best film that it could make,” Fraser said. “It wasn't simply just another job to Denis. This is his life. Every breath that he'd taken happened after reading the book and up until this point was in preparation for making this movie.”

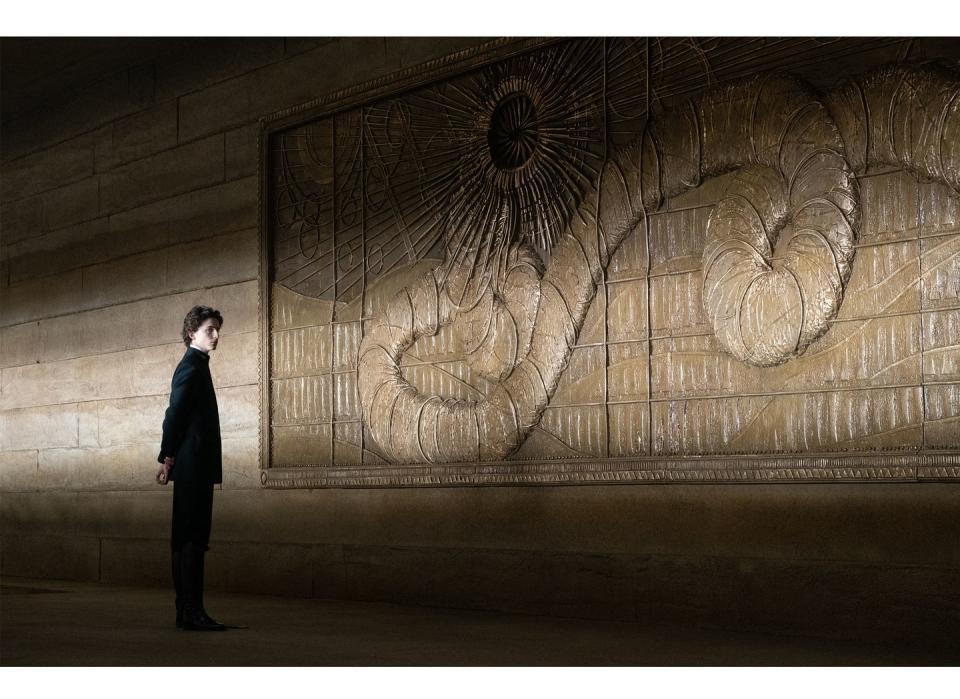

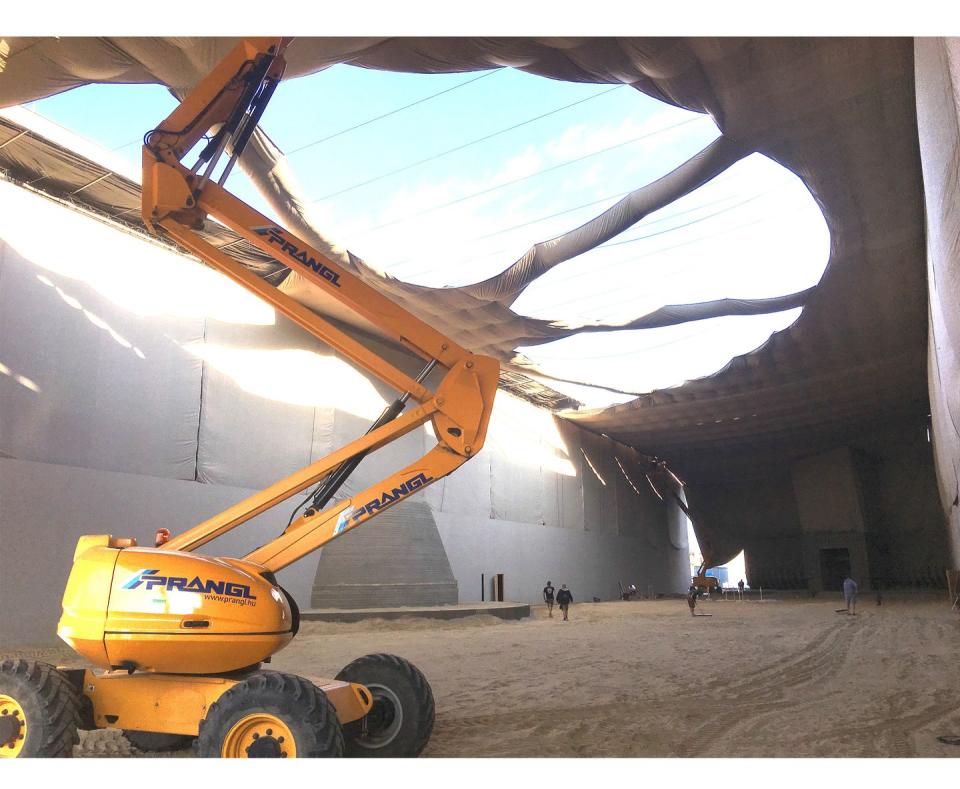

When we first meet the sandworms in Villaneuve’s Dune they have been immortalized in a work of art adorning a wall of the new Atreides palace on Arrakis. “The sandworm was something that was extremely iconic, extremely dangerous to think about, because we knew that, well, the fans of Dune would just wait to see that sandworm,” Production Designer Patrice Vermette tells me. “In early discussions with Denis, we thought the sandworm should not look like a monster. As opposed to being a scary monster, the approach was that this should be something that commands respect.”

What’s often lost in other adaptations of Dune, is the ecological nightmare of the story––that this is about a world that has been pillaged by outsiders for its natural resources with no regard for the native inhabitants. Visually, Villeneuve’s Dune takes great care with this part of the story––which is why we first see the sandworms in a work of art.

“We were thinking that the murals would have been probably made by local artists a long, long, long time ago,” Vermette said. “The locals, they respect these worms. Yes, it's a dangerous animal, but they see it as the one that you should respect, the most powerful thing on Arrakis. That's why that worm is made and the mouth is like a sun, so it's a more religious aspect of the worm as a divinity and something that should command respect.”

For the design of the creature itself, Vermette said they were inspired by whales. Rather than monstrous fangs for teeth, they went with long, delicate teeth that they saw more as a filtration device.

Elsewhere, the team used the film’s visual style to translate this environmental theme. Fraser intentionally removed any green from the film. The Fremen, humans who call Arrakis home, dream of transforming their planet into a lush, fertile, and green ecosystem.

Near the end of Dune, Paul arrives with The Fremen to an old ecological station, where Fremen Doctor Liet Kynes wistfully tells him that the planet “could have been a paradise.” Inside this lab are a few precious little plants, and the first green we see on Arrakis.

“It was just a barren wasteland that was being harvested and mined and it was being stripped of its goodness––Herbert's way ahead of his time and he's talking about very much a contemporary problem that we've been having,” Fraser tells me. “When we get to that green, it's kind of almost like you're seeing in color for the first time, or it's like if you're color blind and suddenly you can see color.”

For a story set far into the future, what is essential to the DNA of Dune is that it is old. It’s as old as it is big. This is a book about ancient mysticism. For a sci-fi staple, there are no computers and very little technology as a whole. A misstep of other adaptations have been to make it feel very modern, which is why Lynch’s seems so entirely eighties today (complete with Sting!). So part of the successful visual design of Villeneuve’s Dune is establishing this history in every scene, and by focusing on many of the very real-world environmental themes.

For this reason, Costume Designer Jacqueline West looked to both history and nature for inspirations on Dune. As West tells me, when Villeneuve first asked for her to work on Dune she at first said no. Not because this was the unmakeable movie, but because it was sci-fi. She’s never seen a Star Wars film, and save the sci-fi-adjacent League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, has never done a sci-fi film. But that’s exactly why Villeneuve wanted her—because he didn’t want to make a typical sci-fi film.

Perhaps second to the sandworms, the stillsuits are the other most iconic image in Herbert’s Dune. Water is the source of all life on Arrakis. It’s sacred. It’s precious. And Herbert describes the stillsuits, which are garments that recycle the body’s water for drinking, in excruciating detail in Dune. They had to get it right.

For the movie, West had to make 250 bespoke Stillsuits—each one form fitted to each actor that couldn’t be mass produced.

“To survive in an environment robbed of its resources without any thought to the consequences, you need something to survive, but it has to be somewhat attractive on these very iconic actors,” West says. “And they have to be able to move and it has to be realistic.”

For the color, West matched the exact color of a sample of rocks and sand in the Jordan desert. Inspired by the Tuareg people of the Sahara, West wrapped the suits and the actors’ heads with gauze as a way of keeping sand out of their faces.

As a bonus, the stillsuits were practical, given that filming took place in the real desert. C-3PO actor Anthony Daniels has long talked about being trapped in a restrictive, painful metal suit in the unrelenting desert heat and cold while filming Star Wars. While costumes may look like the clothing of the future on the screen, they’re often not quite so high tech in practice. But the stillsuits were a different story.

West remembers the first time Timothée Chalamet tried on his stillsuit: “His mother was a ballerina so he's very physical and lithe and graceful and heroic. He put it on, and of course he loved it, because right away he felt like Paul Atreides,” West says. “He started doing a sand walk, crawling on the floor, and jumping and kicking and doing all of the martial arts his mother had taught him.”

West says she took inspiration from the Romanovs for the doomed Atreides uniforms. And Francisco Goya paintings for Lady Jessica. She looked at spiders and ants for designs for the Harkkonens. She based the mystical, witchy Bene Gesserit off Marseilles Tarot cards and medieval chess pieces.

All together, it gives Dune completely unlike the clinical or dystopian or hyper-technical science fiction we usually see. It exists in a universe of its own.

“I think that’s the timelessness that Frank Herbert intended. He wrote a timeless masterpiece,” West says. “So I think all these different departments really helped Denis pull that off, but he is a visionary and he has incredible taste.”

You Might Also Like