Uncovering the Emotional Weight of Elsa Peretti's Brilliant Jewelry

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

I woke up this morning to her image staring knowingly into the camera. The image was part of her obituary. Peretti’s kohl-lined, world-weary eyes seemed to ask “Who are you to look at me?”

I was unexpectedly pierced with sadness. Not just for her. For me.

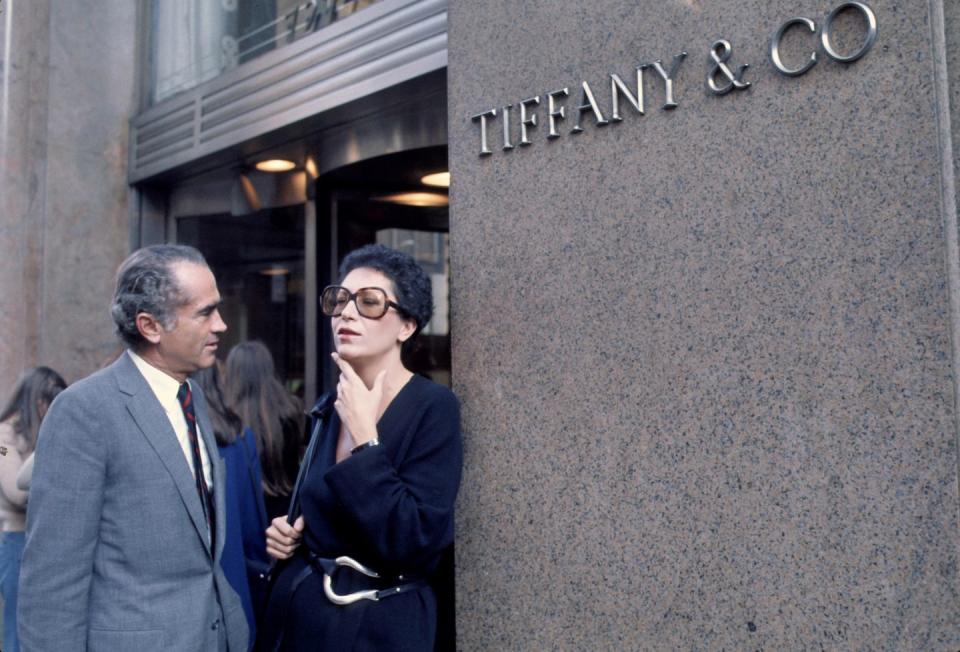

My mother, an unheralded writer, singer, artist, was drawn early on to Peretti’s jewelry from Tiffany’s. The familiar robin’s egg blue catalog started featuring her striking sterling silver designs, which seemed very avant-garde, in the mid-1970s. The open, off-center heart necklace, the tear-drop shaped earrings, the bone cuff (which Gal Gadot would wear, in gold, in Wonder Woman) and Diamonds by the Yard, some of which were sold for $89.

On my 21st birthday, I spied a small blue box on our kitchen counter. I untied the white satin ribbon and opened it. It was an Elsa Peretti Diamonds by the Yard necklace. It was delicate, yellow-gold, with a diamond an eighth of an inch in diameter (I’m not good at judging carats.) The stone lay perfectly in the notch of my neck. I vowed never to take it off.

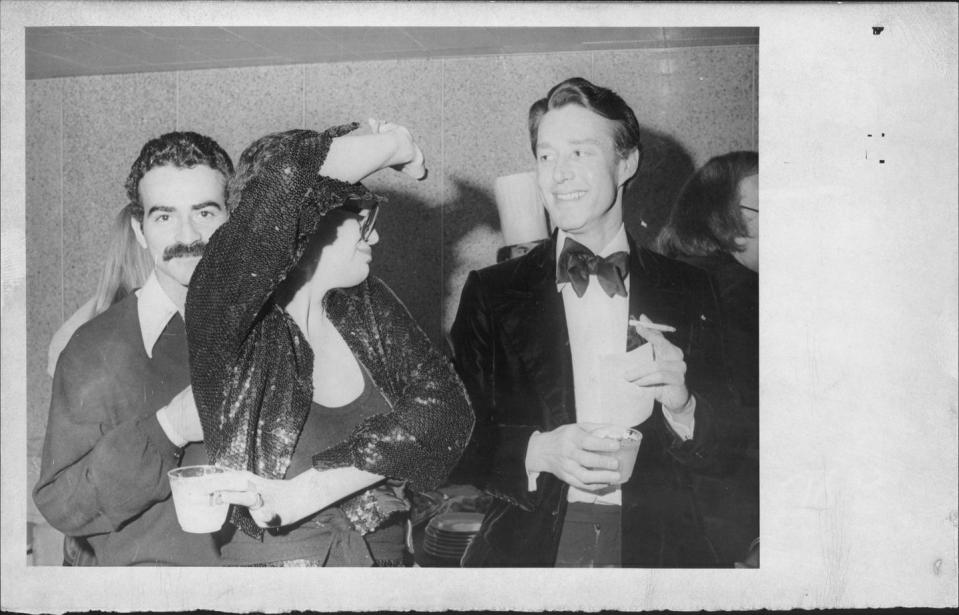

People would say, “I love your necklace,” and I would reply “It’s Elsa Peretti” with great pride. I became somewhat obsessed with her, hoping for the occasional glimpse in the glossy magazines: tall, regal, rail thin, posing with Halston or at Studio 54 with Warhol and his crowd. I saw in one shot, that she smoked Gauloises. It reminded me that on a high-school trip to France, I bummed them from our bus driver and attempted, unsuccessfully, to blow smoke rings from the back row, as far away as possible from the former nun who was our chaperone.

In thinking back, I connect her with Rudy Gernreich. I still remember the shock at seeing a photo of a model who, incidentally, looked like Peretti in a topless bathing suit in Life magazine. I was on the cusp of puberty and did it ever fascinate me—probably the first time I had seen a photo of breasts, not counting the National Geographics at my grandmothers.

The sadness I felt at Peretti’s passing evokes a sense of loss, of time past, of gifts from my family I had lost over the years.

My mother had given me a ring from my great-grandmother, Caroline FitzSimons, for whom I’m named. She was born in 1861, a time when it was the custom to fashion jewelry containing a snippet of hair from a loved one. This was a gold rectangular signet ring with a clasp that opened to a small window encasing a lock of her auburn hair. I wore it on my pinky from the time I was 15.

One afternoon in high school, I was taking off my shin-guards after a field hockey game when I realized the ring was gone. My friends dashed outside with me, and crawled around the field, muddy and torn up with fresh divots from the slashing of our hockey sticks. I never found it.

I wish I could say it was the last piece of jewelry I lost. But no. I cared deeply for these treasures lovingly bestowed on me. And no one could have punished me as severely as I did when each was lost.

Looking back, the list of vanished heirlooms is long. I lost a Great Aunt’s sapphire ring in the old Ritz bar on Boston’s Newbury Street, after too many Margaritas. The next morning, I had the humiliating experience of waiting for the place to open and, again, crawling on my hands and knees under the bar stools while someone vacuumed. I wanted to look at the contents of the vacuum bag, but couldn’t bring myself to ask. At the time, I was working at the Boston Symphony with its music director, Seiji Ozawa. I was miserably hungover and sleep-deprived. He noticed and I blurted out what had happened; after rehearsal, he drove me back to the Ritz to look again. He had such strong ties to his own mother, very much alive in Tokyo, that he felt it was a mission to help me. It was in vain.

Another time, at Tanglewood, the Boston Symphony’s summer home in the Berkshires, a piece of turquoise from a small fetish necklace from New Mexico I was wearing fell off on Ozawa’s lawn during a party. I sheepishly and stealthily returned to hunt for it. He was studying for that night’s performance and saw me lurking. He again insisted on helping and told me it was bad to wear that necklace if one of the animals was damaged. (I assume he meant bad karma although that was a word he didn’t use.) That time, I got lucky and found the turquoise wing of the small eagle at the center of the necklace.

I’ll spare you a recitation of the many more instances of the carelessness I showed with the objects that meant so much to me. Especially after my mother died when I was in my thirties, I would torture myself in sleepless nights, going over the list of my lost and irreplaceable family treasures.

Now a shrink might posit that losing so much of what was entrusted to me might represent rebellion or a resentment of assuming the mantle of adulthood—becoming a grown-up. But I don’t buy it. I just know it wasn’t that.

In a Proustian way, Elsa Peretti’s death has brought me to not only a place of regret but also of love; Peretti’s jewelry somehow has become freighted with a mother’s love.

I have managed to hang on to the Elsa Peretti necklace. I keep it in a small Japanese bowl on my dresser, painted with dancing rabbits. I don’t currently have the necklace with me, since I have been marooned in Montana, now waiting for my second shot. But as soon as I’m able to return home to Massachusetts, I will once again fasten its clasp firmly around my neck, in homage to Elsa and Mom.

You Might Also Like