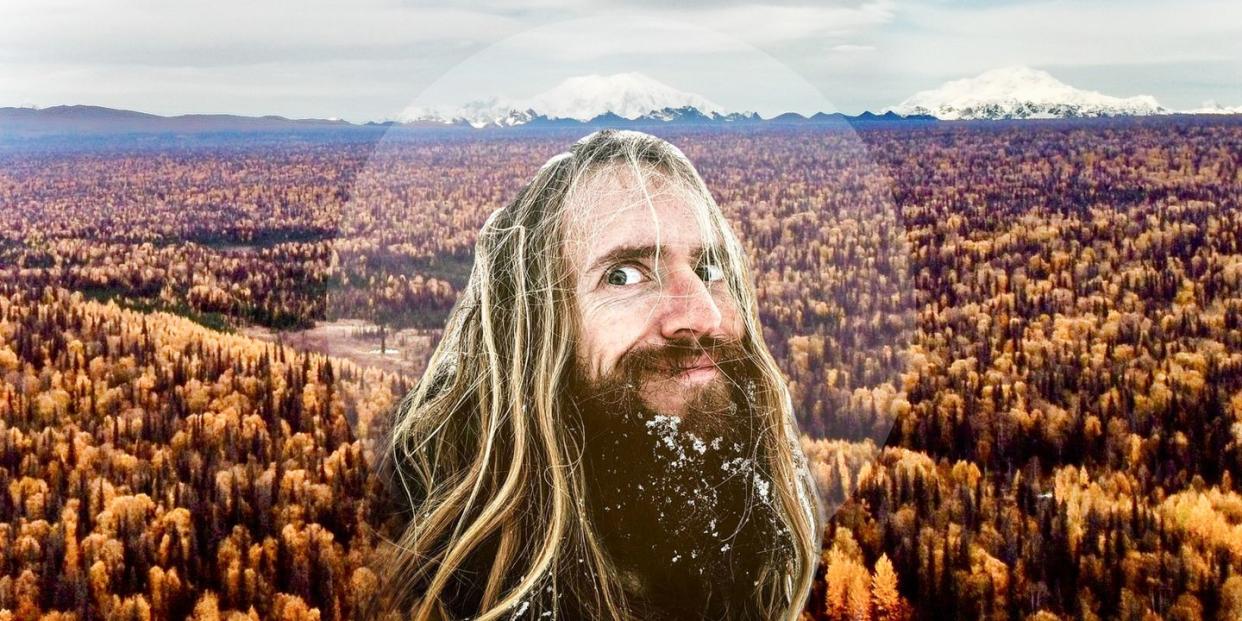

Tyson Steele Was Alone and Helpless When His Cabin in Alaska Burned Down. This Is How He Survived.

I.

See the man. His beard hangs with ice. He reeks of smoke and burnt plastic. He stokes the dying fire. Around him in the gloom smolders what he’d known and cherished and what that fire turns now to ash: his cabin, his home, his dream of living quietly here in the Alaskan wild. His dog is nowhere to be found.

He rises, stumbling forth for more wood. The snow lies chest high, too deep to travel far. The nearest road is some 45 miles off. His closest neighbor is an abandoned cabin a mile into the bush. It will take him days to cover just a quarter of that distance. If he falls through ice and into streams he will surely freeze and die. Even if he tries, he has no map to know the way.

The Valley, they call it. Matanuska-Susitna. Carved by glaciers and cupped by three mountain ranges beside a river that makes its way to Anchorage. But the man is up country even from here and it is December. Out here, no man or woman or dog ought to leave its home in December.

The man limps down an embankment. His muscles are weak from carrying logs. A ligament in his knee is torn from shoveling snow. He wears only pack boots over long johns. He has also rescued from the fire a flannel shirt, a wool sweater, a cotton long-sleeve, a summer jacket, a down jacket, food cans, sleeping bags, blankets, and a rifle from the fire. He dropped his phone escaping the flames. It is lost now beneath snow.

The night before the fire, the man had texted home, a joke on the family group chat. He sends texts every ten days or so. It’ll be that long before anyone worries and then at least a week before someone reaches him here. His next supply shipment won’t come by plane until the spring. A plane will have to be called. Thirty days, he reasons, before help arrives. If help knows he needs it. If help is able to come.

Dawn appears ice blue, then pink against the snow and the tips of the willow trees. The days are short. The sun will hobble along the horizon for some five hours before retreating. Then the wind will force temperatures below minus twenty and the blackest night will once again steal across the face of the wild.

The man throws more wood onto the fire. He has been working for ten hours, he figures, since the start of the fire near midnight through the sunrise. Hours first spent shoveling snow to smother the flames and now tossing logs to prolong its life. It burns where once the pantry of his home stood, now scorched plastic and soiled glass. What food he had recovered is barely edible. Burned sugar, congealed. Canned bricks of charcoal, some containing beef stew and some summer sausage and one mayonnaise and one tomato paste. And one pineapple, though the man is allergic to pineapple.

By the fire, the man calls out for his dog. Phil! Phil! And though the woods do not answer him, the man longs to believe his friend has returned. He speaks to him: You have to stay warm, Phil, you have to come close to the fire. I’m sorry. It is all my fault.

He still has his rifle, though he has no bullets. He used them during the night’s inferno. He wishes he had saved just one. The man had wanted to live here at the edge of all things, away from the roads and the cities and the mark of people. And here he is now at the edge of it all. He leaves the fire. He continues to dig.

II.

The land came cheap: forty acres for a third the going rate. The man, whose name is Tyson Steele, bought the land before laying eyes on it. He had been nomadic since college. He’d lived with his dogs in a shipping container in Escalante, Utah, growing his own food. He’d traveled to Mexico. He’d taught in China. He spent summers as a dockhand in Juneau where he would fillet and process and freeze and package and ship some 20,000 pounds of fish per season. He had a master’s degree in English. He was 28.

He first saw the land from the air in the fall of 2018, a year before he would settle there. The land looked flat. Then Alaska’s mountains opened crescent-like along the horizon. Snow-capped peaks of Denali rose up from the north. Wild and rolling and untrampled land stretched 500 miles to the west. It was like the edge of the world and it was perfect.

But the terrain was treacherous and there was nowhere near to land. So the pilot took them down into a lake three miles from Steele’s plot. With his chocolate Lab, Phil, and 2,000 pounds of gear, he hiked inland. It was like swimming through trees. Willow thickets, bogs, black spruce, mosquitos and gnats, and six-foot devil’s clubs with spines of reverse barbs. He pulled his gear in a sled-converted wheelbarrow but everything was soaked and ruined. It took a day to travel just half a mile.

Up higher the land was dry and near fresh water. He and Phil could make a home there. Phil was now his only dog. Back in Escalante, when the nights dropped below freezing, he would huddle in the shipping container with the lab and his two beagles, Abby and Norah. But Abby died of old age, and Norah, too, was old when Steele left with Phil for Alaska. He had wanted her to stay with his parents in Utah where there was a yard. She was there when he left, and she ran after his car. He found out later she was hit by another instead and killed. She’d run for almost five miles. It was all his fault, he felt.

One day Steele and Phil came upon a cabin. It was made of one-by-fours and plastic tarp with a roof arched like a Viking longhouse. An old airplane engine converted into a sawmill generator and greenhouses for tobacco and tomatoes stood beside it. There was an outhouse, a tool shed, and a small airstrip for a biplane, the only way to deliver supplies in this part of the backcountry. Helloooo? Steele called in fear. A large, hunched man with rotting teeth came out and lurched toward Steele. The hermit, a man by the names of Mike Loeffler, had been living there for some two decades. He had not seen faces for some time. He smiled, happy to see Steele and Phil. Steele would spend many nights with the Loeffler, who told him stories about Vietnam and the horrors he had seen as a gunner protecting heroine shipments in Laos.

But Loeffler was an old man and he was dying of stomach cancer. The following spring, he poured Tide on the floor of his room to ward off bears, then lay down and died there. Alaska troopers carried him off. His last words to Steele whom he had promised the property: look for the shovels, do not trust the neighbor, do not trust the Catholic Church.

In the fall of 2019, he and Phil moved into the hermit’s cabin. The place stunk of body odor and mildew. Steele cleaned the cabin and rebuilt the shower. He kept the same mattress. He slept in the same room where the hermit had perished. The floor still smelled of Tide.

Steele and Phil settled in for the winter, their first in the bush. Their supplies were already gathered. In bed beside Phil, Steele read The Lord of the Rings. One night he fell asleep after finishing the chapter in which Gandalf faces the flames of the Balrog at the Bridge of Khazad-dûm. “Fly, you fools!” implores the wizard.

The fire came that night.

III.

The sun staggers up on the second day but Steele is under the snow and he does not see the light. He’d dug a trench the size of his body, covered it with some lumber and then a tarp and then snow. He’d crawled inside and slept for fifteen hours.

He emerges from the hole now. He limps across the snow toward his ruined home where smoke still billows. It is much too thick for Steele to pick through. He decides instead to dig another shelter in a nearby hill. He encircles himself there with snow walls and puts a fire pit in the center. He carries coals from his cabin. He huddles and cooks his canned remains, leaving only to scavenge for supplies and look for Phil. Before dusk he staggers through the snow. I’m so sorry, Phil. I'm so sorry, Phil. I’m so sorry, he mutters again and again. He searches for tracks by the woods where his friend might have flown from the fire.

The sun dies. Steele huddles for warmth, burning logs and scavenged National Geographic magazines from the frozen tool shed. Steele reads the magazines as an offering before the flames. They tell of the lives of the apostles and of big data. He is sorry to burn them. He sleeps.

Long after dawn Steele awakes and the fire is out. Temperatures have fallen below negative fifteen. They will continue to fall each day until the Alaskan winter reaches minus forty, temperatures at which the heart and brain and organs stop functioning and a man can freeze and die within an hour.

Steele hurries from the cave to his burnt cabin for coals. But that fire too is gone, the smoke expiring in the late morning air. Fuck, fuck, fuck, fuck! He makes his way to the toolshed, rubbing his hands together, for he has no gloves. In the shed he finds an acetylene torch and four flint starters, all frozen. The torches mix oxygen and gas to produce a bright welding flame. But they are frozen. He tries one without success. FUCK! He throws the starter across the shed. He tries the second and the third but both are also dead. His hands are without feeling. He can barely move his fingers.

He fiddles with the torch again. It hisses. And then it sparks. He grabs a magazine and lights it, and then he steals back to his cave and then to the charred cabin. It is safe to enter now. His wood stove stands in ruin, but it is functional. He decides to build his next shelter here on the rubble around that which destroyed everything.

On the fifth day he oversleeps once more. He wakes and the cave fire is gone again. The fire in the wood stove too. The torch spits but will not light. YOU SON OF A BITCH! WHAT THE FUCK IS WRONG WITH YOU, YOU STUPID FUCK! His fingers are numb. His pinky is solid white. He tries to move the wires on the torch but still it does not catch. FUCK! FUCK! FUCK! He fumbles for over an hour. He has read Jack London’s To Build a Fire a thousand times and taught it to near a hundred kids. He envisions the end: He will take his sleeping bag and his blankets and his jackets and curl up in the back of his cave.

He rises as he remembers the cans of gasoline in the shed. He picks up a Bowie knife and limps to a tree. He cannot move his fingers, and so he squeezes his hands together on the handle and uses his weight to pry the birch’s skin. A chunk peels free and he soaks it in gasoline and returns to the cave. He manages a spark. The bark ignites. I HAVE MADE FIRE! He smiles but he knows he cannot let this fire go out. The welding torch will soon die forever.

He sits by the cave in the firelight and for a moment, looking out at the snow and the pale sky and the rubble of wood and plastic, he finds it all beautiful. But the thought is soon replaced by guilt.

I’m so sorry, Phil. I'm so sorry, Phil. I’m so sorry.

IV.

Steele awoke in the cabin at 1 AM because it had become too cold to sleep. He had forgotten to stoke the fire that night and the coals had died down. Phil shuffled around as Steele grabbed a headlamp and stepped outside for wood. The sky was black and clouds covered the moon. Steele was tired and when he returned to feed the flames he put the logs to the side and fed the stove cardboard instead. He knew he ought not feed a wood stove cardboard since the cardboard could rise and set fire inside the chimney. But he was cold and half-asleep, so he did it anyway and returned to bed.

He closed his eyes. He could not sleep. Behind his lids the room was getting lighter and when Steele opened them he saw a bright hole growing in the ceiling and dripping fire like a drooling mouth. He went to the kitchen and tried throwing water on the flames but the fire spat. He went for an extinguisher but when he pulled the pin he heard only a puff. He figured it could be a chimney fire so he ran outside for snow to shovel onto the coals and use the steam to kill the flames. But when he fed the stove it hissed and steam exploded into his face and scalded him and filled the house with smoke. The fire spread.

He raced outside. Against the cold black sky his cabin was silhouetted orange and flames ran along the frame. Lit cardboard had escaped the chimney and set fire to the plastic roofing. In minutes, he knew, it would consume everything.

He ran back inside to his room. Phil was huddled in the corner of the bed, hiding from the flames licking him. Phil, we have to go! Steele yelled as he began grabbing what he could. Phil cowered. Flames began to swirl. Steele pulled at Phil’s legs but the animal was 110 pounds and impossible to move. The fire encircled them and Steele lost his vision. He could no longer see his friend. He yelled for Phil to run and follow and then Steele fled through the fiery doorway and the snapping heat, into the cold and into the night.

V.

He tells himself he will be found on Christmas. There will be a flyover. Some friend or family member will send a care package, cookies or a wrapped gift, and the pilot will see the ruins and radio for help. Help can come only from the air since the snow is too deep to travel here. Steele finds a piece of chalk and makes marks on the stove. Christmas is just over a week away, he believes, but he cannot be sure what day.

He continues work. He gathers scrap A-frames and props them up around the stove. Walls are greenhouse tarp and plastic and scavenged rat-infested insulation. He stands on a charred wooden ladder and hammers boards together into a roof. The temperature falls below minus twenty and the metal nails freeze to his fingers. He can only hammer one at a time before retreating to warm his hands. The shelter takes days.

He can do no work in the dark, which comes near 4 PM and lasts until after 10 AM. He can barely sleep for fear of losing the fire, so he reads magazines and books from the shed. One tells of pilgrims and their voyage into the dark forests of the New World and Steele reads story after story of the starvation and death that came for each pilgrim. He tries a crossword book. But the clues are for children and the answers are “house” and “cat” and “dog.” Steele talks to himself and tries to remember the words of a book he has been writing for years. It is a fantasy like The Lord of the Rings but about an outsider who lives on the corner of an Empire in a world of banned magic. Steele sits by the fire, talking. The shelter is small but finds comfort in small spaces. He camped in Utah canyons as a kid and lived in a frigid car in grad school and then an empty professor’s office after teaching. At eighteen and while his classmates went off to Europe and the Bahamas on break, Steele had locked himself in a box for three days of complete darkness.

The sun rises and Steele begins work on an “SOS” stamped into the snow, letters fifteen feet tall. It snows, covering the tracks. He waits a day. He begins again. He shovels ash from the cabin to fill in the letters. Repeat.

Each night he panics. He wakes every two hours. He claws at his sleeping bag, preparing to flee imagined flames. He loses track of the days, making chalk marks at night then forgetting and then making more again at dawn. One morning he awakes to snow. The air feels warm. Gray clouds cover a pallid blue. Steele decides this day will be Christmas. He sings “White Christmas” and “Winter Wonderland.” He feasts on three rations of peaches, which give him canker sores. He walks to the airstrip where to the north he can see the snow-capped tips of Denali. His family are opening gifts now and maybe expecting his call. Maybe they have already sent a plane for help or to drop a gift. But who was he to deserve such a gift?

Night comes without a miracle. There has been no Christmas flyover. No one is searching for him. The temperatures continue to fall.

One day the sound of fighter planes. Steele can hear them practicing maneuvers over the mountains. The noises grow down the valley. Two jets duel and roar some 10,000 feet above. In the middle of his small airstrip, Steele watches the mock dogfight in awe and then he begins jumping and yelling and flailing his arms. But they cannot see or hear him. The engines sound for a time and after an hour of Steele’s shouts, the planes turn and then they are gone.

The silence breaks occasionally with the burst of frozen sap. It explodes like gunshots from the trees. Bang! Bang! Echoes. Then silence again.

Another day. The crunch crunch of snow and buried metal. Steele awakes. A creature of a thousand pounds passes just outside his shelter. He has seen the tracks before and he begins dashing pans against the stove and screaming. I WILL SHOOT YOU! The hoof falls recede and Steele leaves the shelter. The moose, large and dark against the snow and having made its way back toward the trees over the “SOS,” his ears downward, turns to face the man. Awe, anger, envy over the animal’s fur, the urge to run, the desire to kill and eat, hopelessness, despair, thoughts of death and the rifle. If he had just saved one bullet for the moose or for himself. But rescuers will think he had starved and had eaten Phil, and Steele cannot bear this thought. He remembers how Phil would try and help him weed in Utah by chewing at the plants. He sees Phil playfully dive under the legs of Norah and Abby even when he got too large. His favorite word was “hike” and his ears would perk when Steel would say, Hey Phil let’s go for a hike! How could he consume such a creature?

By the woods, the moose chews on some willow trees. And then it turns quietly and walks off into the wild.

VI.

Phil did not follow. When Steele escaped the fire and dropped his gear and ran around the house for his rifle, his lab was gone. Black smoke swirled around his face. He tried to reenter the flames. He dropped down. He crawled. But the fire was too hot and the smoke choked him as all the while Phil began to howl.

It was an awful, breathy howl, like a wolf. An injured howl that sounded from everywhere at once. EHHHAAAAROOOO! Rifle in hand, Steele ran back to the other side of the house where his room and Phil were ablaze. Phil was howling and Steele began screaming. He had four rounds in his rifle and standing there in the snow awash with fire light he pointed the gun into the flames. He didn’t want Phil to suffer any more because suffering was worse than death. And so Steele pointed his rifle into the fire and plastic and wood and he started shooting. One, two, three shots. And all the while he was screaming and Phil was howling. EHHHAAAAROOOO! And after the third shot Steele thought that maybe the last bullet should be for himself. Maybe he would follow Phil into the night for it would be easy to follow in this way. But the thought scared him so much he fired the last shot into the fire. Still he heard the howls. He had missed each one. He had failed his friend and he was still alive and Phil was still burning. Steele could take no more and so he screamed again, a horrifying yelp full of pain and anguish that lasted for minutes and would have been heard for miles across the dark wilderness if a soul existed to hear it, but there was none.

Hoarse, Steele collapsed in the snow. Everything was now nothing but a crippled fiery heap of wood and plastic and howling. Then the bullets began to explode. Five hundred rounds he kept inside burned and shot off in the night like a machine gun, sending echoes across the forest. Steele ran. He ran for cover and then he turned and ran back toward the salvo for his food. The bullets stopped, but the air was too hot, so he began shoveling snow into the burning. He shoveled and shoveled, trying to think of nothing but the shoveling. The howling ceased.

As the flames retreated he could see. Everything was ruins. And then Steele saw Phil.

His body lay in the corner of the room, still on fire. He approached with the shovel and reached in to touch the remains. Something moved and rolled out of the fire: Phil’s head. It was mangled and charred but Steele could still see the Labrador's profile. He picked up the head even though it was still hot and hurt his hands. He set it down with him next to the dying fire.

I’m so sorry, Phil. I’m so sorry, Phil. I’m so sorry.

VII.

January. The coldest night ices into the coldest day. Temperatures slump past negative thirty and Steele huddles in the shelter, nearly hugging the stove. He burns his hands on the metal. The chalk marks announce the seventeenth day but he cannot be sure. He lies in his two sleeping bags. He pulls them up over his face like a scorched cocoon of frost, body odor, and decay.

Racing thoughts. He worries an eyelash will give him an eye infection. He fears his food has poisoned him. Hunger never leaves. He eats now one or two cans a day, scraping the bottom and mixing in and sloshing water and ravishingly lapping every last calorie. He’d been defecating daily by running through the cold to an outhouse still intact. There from the pit of bile, rising warmth had frozen across the seat like long dirty fingers, reaching. He refuses to enter the cold now. He pees in a bucket by the stove which freezes almost instantly. The stove can only warm the shelter by ten degrees. A jar he filled with water and left on the floor froze and cracked and then burst in his sleep.

Above his head by the wood and the stove pipe, mice scurry and squeak in search of warmth. The light from the fire moves mechanically against the wall and Steele mistakes it often for the headlight of some snowmobile. The mice squeak and squeak and Steele cannot move from his sleeping bag and for the first time he thinks he will surely die. He hopes it will come tonight in his sleep. Though he could walk out of his shelter now and sit in the snow and perish, he is scared of the conscious pain.

Racing memories. He thinks of that box in his backyard where he locked himself for three days at eighteen. He had wanted to test his mind and so there he sat listening to a song on repeat. Vangelis, “Ask the Mountains.” The only lyric he could decipher whispered over and over again: don’t follow me, don’t come after. He thought someone was following him. Stop following me! he had yelled. He had scrawled on the box in marker a wood cave drawing, a Chef he called “Morrison.” Now on the stove Steele redraws the chef with chalk. He prays to the image which feels like a Buddha. Help me, Chef. Help me, he begs. He had no girlfriends back then. He would rather go out and hike the canyons alone. But he thinks of people now, girls and friends in grad school who had shown interest in him but whom he had never called. Alaska had waited but perhaps he was wrong to think it was waiting for him alone. He thinks now about backpacking with a boy of his own and teaching the boy about the wild.

Don’t follow me, don’t come after. His breath freezes before him. The cold and the hunger and the mice and the fear of fire. He sings the song and thinks of a ridge line 10,000 feet up and snow cornices and limestone fins and a rock as red as blood and a colony of ladybugs like a sanctuary beneath. Shooting stars over Escalante and the smell of sagebrush and the sound of mariachi music over the radio from Mexico. And the noon sun over Greenland’s arctic and cotton grass along the hummocky bogland and purple flowers and scattered reindeer sculls. With the song comes a nature that wasn’t wicked or foul but made Steele’s heart so full when everything else was so loud.

He closes his eyes. He will get out. Someone will follow.

In the box after three days, his friend had come throwing stones and calling for Steele. Steele heard his name but he had forgotten the name was his. He knew it was time to leave and so he had thrown open the box door and he had emerged, his hair long, his face young and eager, the boy divested of all he had been. He was free from the darkness and the lesson he took then was that darkness will always end.

Someone will follow. He opens his eyes.

VIII.

See the man. His beard hangs with ice. He reeks of unwashed days and burning wood. He feeds the abiding fire. Above him, a humming comes from down the valley. The stove marks announce the twenty-third day. The man puts down his blackened oatmeal when he hears a sound above him.

He emerges into the Alaskan dawn. It arrives ice blue, then pink against the snow and the tips of the willow trees. A helicopter circles and the man waves both arms. He climbs aboard the clean vehicle, its doors of glass. He carries only some books and a sleeping bag. He apologizes for the smell.

Aboard the helicopter, he rises above scorched white earth, his home, the charred remains of his dog, and all the things the man had known and loved. He imagines critters eating the dog’s body. He is free and warm and going home and yet he feels so alone.

He enters the cities once more. They terrify him. Cities with street names and taxis and so many people and everything is overwhelming. When in cities the man would often listen on his phone to the sound of chopping wood to ease his anxiety. The sound, his earliest memory.

Tonight, the man stays in a hotel. In the dark he hears only the screams of a woman in a neighboring room. Another man is beating on her and doors are opening in the hallway but no one moves to stop the yelling. The man cannot sleep. He believes he will die here having escaped everything only to perish so close to others. He leaves in the morning.

On the street a homeless woman in a wheelchair braves the cold. The man gives the woman his sleeping bag, one of his last possessions, and then the woman cries and hugs the man and the man hugs her.

And then the man turns quietly and walks off into this new wild.

You Might Also Like