Trump's Jan. 6 Secretary of Defense: 'Nothing Even Came Close' to My 'Red Lines'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

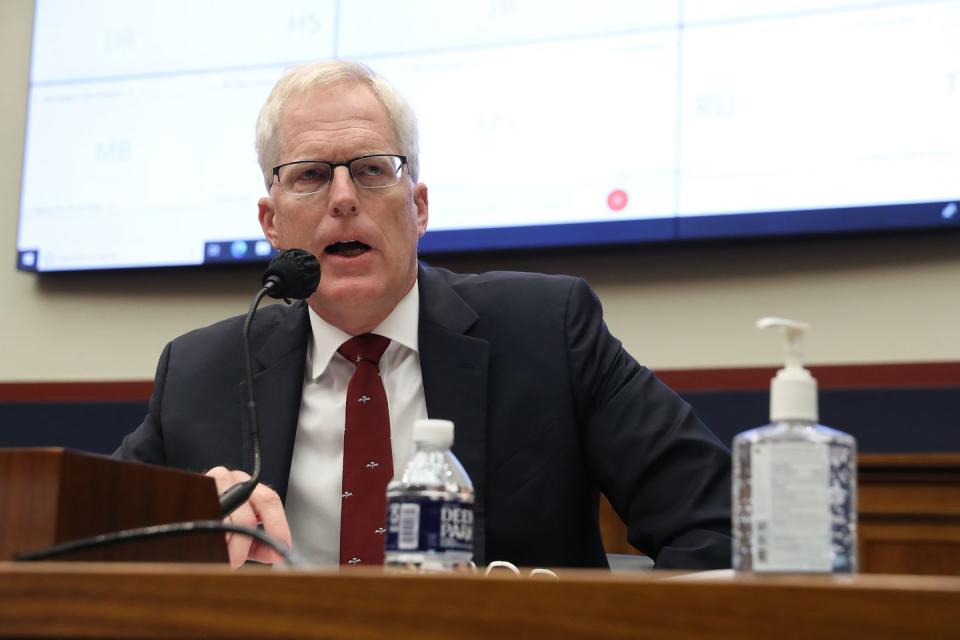

There’s a former Pentagon chief who thinks defense spending should be slashed dramatically, to levels unseen since the days before we invaded Afghanistan. In fact, Christopher C. Miller was in Afghanistan long before he served as acting secretary of defense under President Donald Trump. He got that job on November 9, 2020, which meant he was in the big chair during the attack on the Capitol on January 6. He’s got a new book out, Soldier Secretary: Warnings from the Battlefield & the Pentagon About America's Most Dangerous Enemies, in which he discusses that response. You can read all about that, and how it fits into the events of the day, here.

But Miller’s book offers insight beyond the events of a single day. Below, you’ll find the part of our conversation, edited for length and clarity, where we discussed a career that spanned the National Guard, the Army and the Green Berets, and an even more secretive special operations force before he reached the National Security Council. In it, you’ll find ruminations on government secrecy, how military brass undermined civilian control of the military in their quest to tame Trump, and how Miller now believes that he was “mugged by the neoconservatives who led us into an unjust war in Iraq.”

There are some amazing stories in here from your advanced deployment to Afghanistan in 2001. Did that experience inform your perspective about the relationship between military brass and the rank and file?

No, that was a righteous war, starting it off. I think the questioning came later when I saw how we were doing things, where we plugged in large quantities of conventional forces when I felt that Afghanistan probably should have stayed light-footprint, special operations-focused. Don't go in heavy and try to use an indirect approach through the Afghans. It was pretty clear that making them reliant on us for all of their different needs wasn't going to work well. And that's the parallel to Vietnam, of course. It's not even a parallel. It's right there. You don't have to have a PhD in history. But the Army typically has one way of doing things, and the decision was made. We did it in Iraq, too.

But going in, it was the right way to do it: Small footprint, use commando forces, unconventional warfare, special operators, intelligence officers. It was a great model.

You talk in the book about your experience going to Somalia and meeting some servicemembers. In Africa, we did pursue more of that special forces-driven model, but was there mission creep even with that narrower approach?

Yeah, there was mission creep across the board. And Somalia had become a self-licking ice cream cone.

When you're younger in the military, general officers and admirals are godlike figures. They're unapproachable, and you're taught to believe that only the best rise to that level. And to then be exposed to them, and I'm seeing these hallowed figures come in there, and then you realize they put their pants on just like the rest of us.

Watching how [senior Defense Department officials] would present in National Security Council meetings, you'd realize there were games being played. I'll give you an example: the Iranians and their supported militants in Iraq were shooting mortars at our embassy and our operating bases and our personnel regularly. So that would cause a flurry of activity at the National Security Council to decide how we would respond. And I knew that there were a whole bunch of options being discussed at the Pentagon because I had friends there that were telling me. Then I would go into these high-level meetings and see the general officers and senior civilian officials doing the standard military thing: They provide three courses of action, one completely not achievable, one being completely ludicrous, and then the middle one, the one they wanted. And I'm like, ‘No, actually, there are a whole bunch of other ways to go about doing this.’ That's when the scales started falling from my eyes.

There was an episode towards the end of President Trump’s term, when there was a pretty significant threat from Iran and you presented him with a whole menu of options. Did you try to remove any personal objectives from that?

No, I had a total personal objective, which I will describe in a moment. But I felt that the president of the United States—it's our obligation as his subordinates to provide him with options and not color it. I had seen, or I suspected, that a lot of the national security decision-making apparatus below the president thought he was crazy or unstable. No one said that directly to me, but there was this idea that he was a neophyte and didn't know how to handle national security. Therefore it was incumbent on them to meter, and be very careful in the options they presented.

I found that the president's decision-making in foreign policy—maybe it wasn't in alignment with someone who's gone to Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, but I felt his decision-making capabilities were just fine. Give him the options. And ultimately, you got to say your piece. No one could say they weren't heard. But I had seen this accretion of resistance. If you thought his decision was inappropriate or incorrect, you had the opportunity to voice your concerns. And at the end of the day, if you thought it was so egregious, you had the ultimate right—instead of leaking to the press, you had the right to leave your position and go do something else.

You talk about how your predecessor, Secretary Mark Esper, may have been viewed as an impediment to the president’s foreign policy agenda. Do you feel he was, and is that why he was dismissed [on November 9, 2020]?

Yeah, it was pretty clear that he was not in alignment with the president's worldview. The straw that broke the camel's back on that one was the Department of Defense's unwillingness to provide additional support to border security—and when I say border security, everybody thinks I mean immigration. It was illicit flows of narcotics coming into the country. Secretary Esper and the Department of Defense was very resistant to shifting any resources towards that mission. I sat in some of those meetings, and it was very clear what the president wanted. And I didn't think it was unethical, immoral, or illegal. It seemed to be the essence of what we should be doing for national security.

Was it the president’s priority in that post-election period to withdraw our troops from various theaters?

Yeah, but that was his platform. He came to office committing to do that, and the Department of Defense slow-rolled across the board. He wanted to go to zero. When we presented why we couldn't get to zero before the end of his administration, he accepted that. He was disappointed, obviously, but we presented the risks, particularly in Afghanistan, if we went to zero, that the whole place would come undone, he recognized that. So we stabilized at 2,500.

It was one of the things I was more satisfied with as we transitioned out of the Pentagon. I felt we left the Biden administration a heck of a lot of trade space on how to go forward. They call it in D.C. "jamming" somebody, where you jam them into a corner where they don't have any options. I felt like we had not done that at all. And then subsequently the narrative has changed. "Trump administration screwed us over by releasing the prisoners, and cutting a side deal" and all this crap that was absolutely not true from my perspective.

That was the goal of the president, to get the hell out of there. I think if you look at Somalia, the reduction in forces did not have a reduced capability to conduct counterterrorism operations. Our withdrawal of the vast majority of our special operators there forced Somalis to say, "Oh geez, we can't rely on America to do all our babysitting right now, we're going to have to do something ourselves." And I bet you historians will say, "Yeah, Trump had it right by downsizing the overt"—listen to what I'm saying, overt—"U.S. presence there."

It seems clear that Esper was not really that interested in facilitating this drawdown, but do you think that was the only reason he was dismissed? I ask because during that same lame-duck period after the election, the president was also changing the leadership at the Justice Department as well as at the Pentagon.

Yeah, I’ve got your whole narrative on that one. That they were bringing in weak sisters like me and others to facilitate a military coup. I love that line, that all of a sudden this Chris Miller guy who committed his life to service and had been a political appointee for less than one year of his 30-something years of service, that he was going to throw away all of his commitment to supporting and defending the Constitution against all enemies foreign and domestic. And the crew that came with me, we were a bunch of patsies that were going to be complicit in something completely counter-constitutional. I don't know if that's the case or not, you'd have to ask somebody else.

I don't think it's your specific case, but I feel obligated to ask because of all the changes in that period. When Kash Patel came in as your chief of staff, why did you choose him?

First off, because I'd done operational testing on him for quite a while and found out that all the Wikipedia and public stuff that I'd seen, which made me initially think that he was batshit crazy, proved to be completely inaccurate. I found he was a person that had the best interests of the Department of Defense and the country in mind. You can argue with that all you want, but I found him to be an extraordinarily capable partner.

Our unitary focus, Kash and my focus, was destroying al Qaeda senior leadership. He had very good access to the president. I didn't know the political side of how D.C. works; I knew how the Pentagon worked. I needed Kash, who'd be a wingman, a teammate with me that could protect the political flank. And frankly, that's probably the biggest error that Esper and Mattis made. They were too burrowed into the Pentagon and didn't understand that when you're in that position, you're in an inherently political position, and you need to know what your boss is thinking. I just don't think they had that insight into the White House.

Former Secretary Esper and Army Chief of Staff McCarthy both made public comments that seemed to suggest they were concerned that the president might try to invoke the Insurrection Act. Did you share that concern?

No. You'd have to ask them why they felt that way. I had no concern. Let's be clear, the president is authorized to legally put in place the Insurrection Act. I spoke to the president about that, and he said, "You know, just to be clear, this is my authority. I can do it if I will. I don't intend to." I felt very comfortable that the president understood what he was talking about. And in many ways, having the secretary of defense and the secretary of the Army speak out—and I'm sure they did it with the best of intentions—but it really comes down to lanes in the road. It's not appropriate for them to restrict the authorities and the legal status of their boss.

Here's where we talked about January 6. You can read that here.

You talk about the red lines that you drew for yourself when you were taking the secretary of defense job. Did you ever feel yourself approaching them?

No. Nothing to add. I was worried because of all the hysteria that surrounded President Trump that he was somehow unstable. Going in, I didn’t know the guy. I was like, ‘Well maybe there’s something here. I need to have my moral code and red lines in order so that I’m not surprised. If one of these events happens, I need to be ready for it.’ And nothing even came close.

When he lost and he was saying it was stolen and, basically, he was not going to leave, were you thinking about how things could play out and how you could respond?

I thought that was all political sloganeering and posturing from the president and his political advisers. I was a national security guy, so I wasn't involved in any of those discussions. It’s not how it works. And I didn’t get a hint that anybody planned to stay. You go over to the White House, everybody's packing their boxes and taking stuff off the wall. Calling to find where they’re going to live next. I never got a single hint that anybody planned to stay beyond 12:01 on 20 January 2021.

You served in a number of different capacities. Which time do you remember learning the most?

Great question. Jeez, I’m not good with introspection like that. Ranger School is probably the most defining event. You find out your limits are self-imposed. That’s the cauldron that forms you as a small-unit leader. And then, just working with great Americans out in the field. I’m white-bread, middle class, middle western, and being exposed to the rest of America, that’s just profoundly moving. And I was horribly privileged to serve as a small-unit leader and as a commander.

You write about how sometimes things at the Pentagon are compartmentalized in an unnecessary way, so only some people have the whole picture. But you also were in special operations, so you know some things do need to be secret. Where do you land on how we decide what’s secret in government?

The easy answer is: if somebody's sources and methods, or somebody's life or health is gonna be at risk if the opposition finds out about that. And that’s a very, very small pile of information.

I was in this super secret military unit when I was in the Army, and we're like, "OK, we're ready to go be commandos!" And who's the first person we meet? The first lecture is from the psychologist, and he talked about secrecy in organizations, and he said that when an organization hides their failings behind the protocols of security, you know that you've entered a place where the organization is becoming corrupt and is no longer serving the country.

You Might Also Like