The True Story Behind 'The Trial of the Chicago 7'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The comparisons between America in 1968 and America in the past 12 months are easily drawn: mass protests, brutal clashes with police, calls for racial equity, a contentious presidential election, and a general feeling that the soul of the nation is at stake. With the past feeling less and less distant, the release of Aaron Sorkin's The Trial of the Chicago 7—a movie that revisits a pivotal episode from 1968—on Netflix last fall felt particularly timely.

The film—with Eddie Redmayne, Sacha Baron Cohen, Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, Jeremy Strong, and Joseph Gordon-Levitt leading the cast—dramatizes the infamous trial of eight anti-Vietnam war activists in the aftermath of the 1968 Democratic National Convention, which had seen violent encounters between police officers and protestors. (One defendant would have his trial severed from the rest, and the Chicago 8 became the Chicago 7.)

The trial was one of the most dramatic in American history, characterized by the judge's uncloaked hatred of the defendants; star testimony from some of the era's cultural icons, including Allen Ginsberg, Norman Mailer, Jesse Jackson, and Judy Collins; and disturbing visuals, like the only Black defendant being shackled and gagged in court.

Read up on the Chicago 7 and the 1968 Democratic Convention before the Academy Awards, where the film is nominated six times. Here's everything you need to know.

The lead-up to the 1968 Democratic Convention was already heated.

The 1968 Democratic National Convention was held in Chicago from Monday August 26 to Thursday August 29 to select the party's candidates for the upcoming presidential election. (President Lyndon B. Johnson was not seeking a second term.) The convention followed a year of violence and turbulence, marked by the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4 and Bobby Kennedy (who had been running for the Democratic nomination) on June 5. Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey and Senator Edmund S. Muskie of Maine were ultimately nominated for president and vice president, respectively.

The biggest issue at the convention was the United States's ongoing involvement in the Vietnam War. The summer of 1968 had been brutal, with more than 1,000 American soldiers were dying each month. Ahead of the convention, protests were organized by members of the Youth International Party (known as "Yippies") and the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam (MOBE).

Seeking to tamp down dissent, Chicago Mayor Richard Daley denied all protest permits except one: to hold an afternoon rally at the old bandshell at the south end of Grant Park. Military troops were also deployed to the city ahead of the convention; 6,000 members of the National Guard and 6,000 Army troops joined the 12,000 member Chicago Police Department.

Soon, violence exploded between police and anti-Vietnam War protestors.

Thousands began gathering in Lincoln Park on Monday the 26th to camp out, defying an 11:00 pm curfew set by the mayor. That night, armed police in gas masks swept through the crowds, in a sign of what was to come.

The Grant Park rally on Wednesday, August 28 drew nearly 15,000 people. Afterwards, several thousand protesters attempted to march to the convention site at International Amphitheater, but were stopped by police in front of the Conrad Hilton Hotel, the Democratic party headquarters. Chanting, "the world is watching," the protestors sat down.

Conflict erupted when police used tear gas and batons and protesters retaliated by throwing rocks and bottles. TV networks abandoned the convention coverage for live footage of the street clashes, as a shocked nation looked on. Even inside the convention hall, things got heated: Dan Rather was famously punched in the stomach by security while trying to interview a Georgia delegate being escorted out of the building. The encounter was caught live on the air, and from the broadcast booth above, Walter Cronkite said of the overzealous police presence, "I think we've got a bunch of thugs here, Dan.”

Over the course of four days and nights, in what became known as the Battle of Michigan Avenue, over 600 protestors were arrested, and nearly 1,000 were injured and treated onsite or at area hospitals. Nearly 200 police officers were also injured. Journalists were also clubbed by police and had their film taken or camera gear destroyed.

Later that year, a comprehensive review by the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence found that the police responded to taunts with "unrestrained attacks," and the episode came to be called a "police riot."

In the aftermath of the convention, a grand jury was convened to consider criminal charges against both protestors and police.

On March 20, 1969—after calling nearly 200 witnesses—a grand jury indicted eight protesters with various federal crimes and eight police officers with civil rights violations. By this time, President Richard Nixon was in office, having defeated the Democratic candidate Hubert Humphrey.

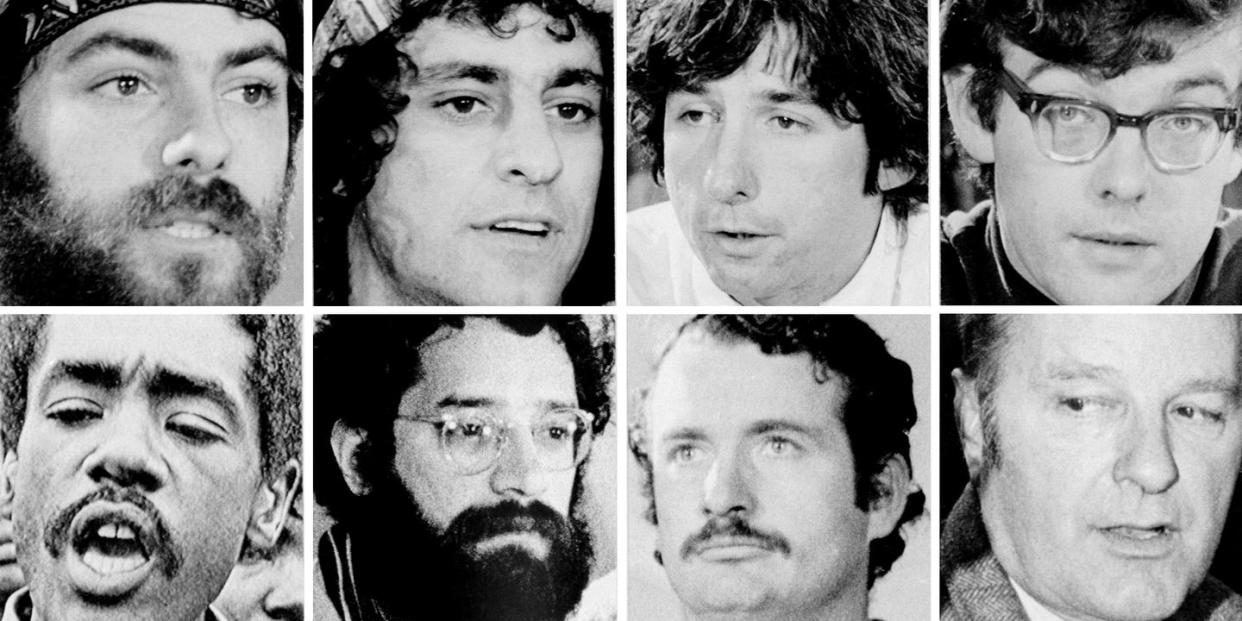

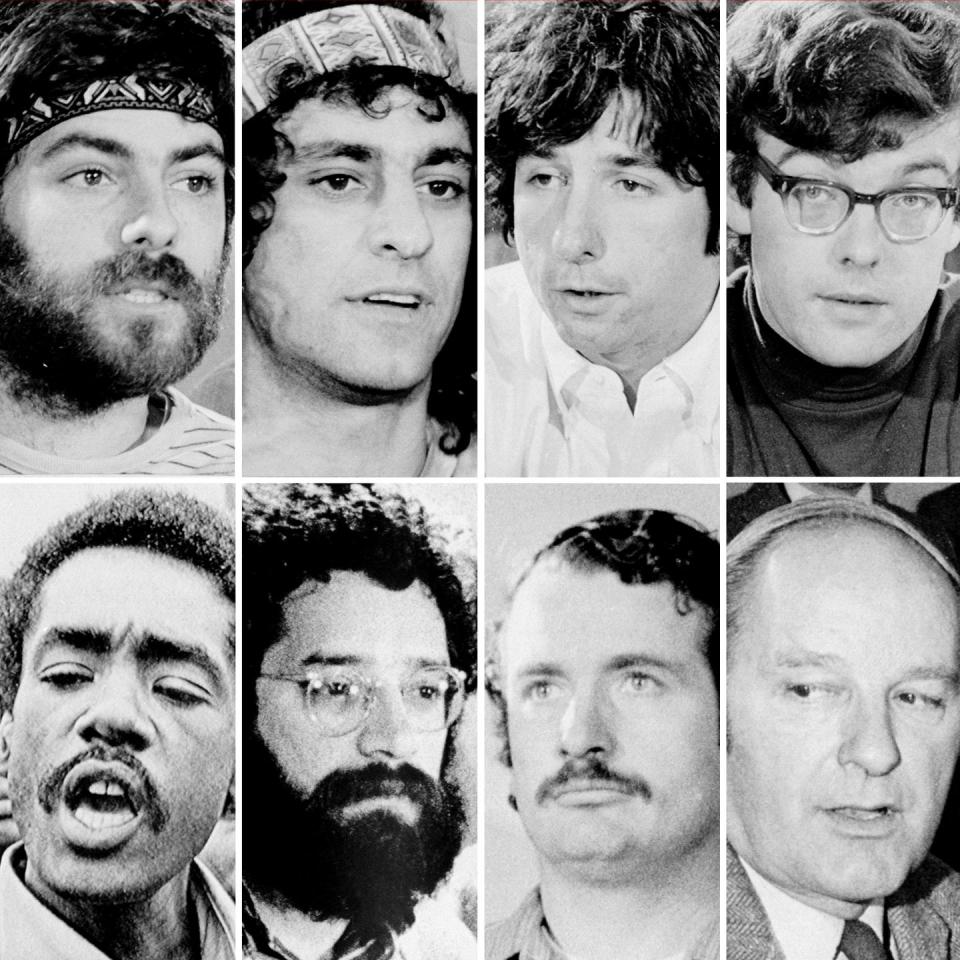

The eight defendants—Rennie Davis, David Dellinger, John Froines, Tom Hayden, Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, Bobby Seale, and Lee Weiner—were indicted under the newly-passed Civil Rights Act of 1968, which made it a federal crime to cross state lines with the intent to incite a riot. (Seale later had his trial severed during the proceedings, lowering the number of defendants from eight to seven; thereafter, the group became known as the Chicago 7.)

The Chicago 7 were a motley crew of activists.

Though there were police officers named in the indictments, the media attention focused almost wholly on the trial of the eight protestors:

Rennie Davis, 27, was the national director of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS)'s community organizing programs.

David Dellinger, 53, was older than the other defendants and had a long history of activism. He had been arrested in 1943 for failing to report for his World War II draft physical and spent time in federal prison.

John Froines, 29, was a chemist.

Tom Hayden, 28, was the cofounder of the SDS (and is also known for his marriage to Jane Fonda).

Abbie Hoffman, 31, was the cofounder of the Youth International Party (also known as the "Yippies").

Jerry Rubin, 30, was the other cofounder of the Yippies.

Bobby Seale, 31, co-founded the Black Panther Party along with Huey P. Newton. He was the sole Black defendant in the trial, and the judge would order him to be tried separately.

Lee Weiner, 29, was a doctoral candidate, social worker, and teaching assistant.

The trial was theatrical and contentious from all sides.

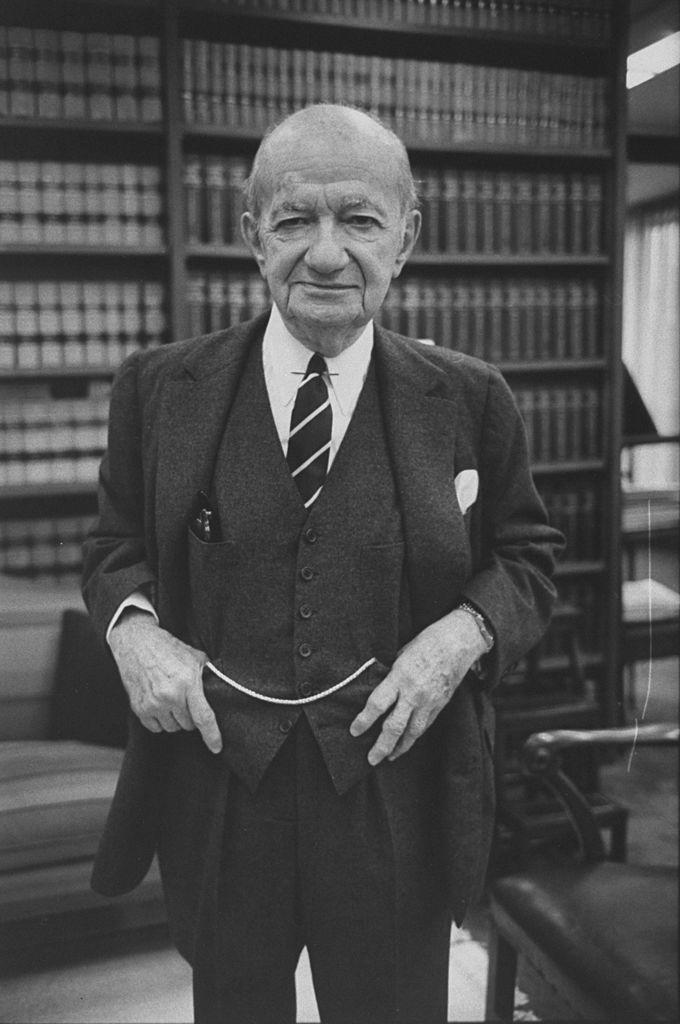

The trial began on September 24, 1969 and was presided over by Judge Julius Jennings Hoffman, United States District Judge of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois. (He had no relation to the defendant Abbie Hoffman.)

The Nixon Justice Department's prosecutors were U.S. Attorney Thomas Foran and Assistant U.S. Attorney Richard Schultz. All the defendants, except Seale, were represented primarily by William Kunstler and Leonard Weinglass, though several other lawyers assisted.

Early on, it was clear that this was no ordinary courtroom. Judge Hoffman was widely believed to favor the prosecution: when Bobby Seale requested that the trial be postponed so that his attorney Charles Garry could represent him (as Garry was unable to be present due to an illness), Judge Hoffman denied the postponement, and refused to allow Seale to represent himself. Seale argued this was illegal and racist, and Judge Hoffman ordered Seale to be bound, gagged, and chained to a chair. Seale appeared this way in court for several days, horrifying many onlookers. Ultimately, Judge Hoffman declared a mistrial for Seale and sentenced him to four years in prison for contempt of court (which was overturned by the U.S. Court of Appeals). The Chicago 8 then became the Chicago 7.

The defendants frequently insulted Judge Hoffman, who often cut off the defense lawyers and made derisive comments about the defendants' long hair. Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin were particularly vocal and pulled many courtroom stunts, at one time appearing ironically dressed in judicial robes. Abbie Hoffman—who blew a kiss to the jury when introduced—also once verbally equated Judge Hoffman with Adolf Hitler. At one point, the defendants draped a Viet Cong flag over the defense table.

The trial went on for four months, with many cultural luminaries being called to testify, including popular singers Judy Collins and Arlo Guthrie; writers Norman Mailer and Allen Ginsberg; LSD activist Timothy Leary, and the Reverend Jesse Jackson.

While the jury deliberated on the verdict, Judge Hoffman cited all the defendants—plus their lawyers —for 152 contempts of court. William Kunstler was given four years in prison for addressing him as "Mr. Hoffman" instead as "Your Honor;" Abbie Hoffman received eight months for laughing in court; Hayden got one year for protesting the treatment of Seale, and Weiner two months for refusing to stand when Judge Hoffman entered the courtroom.

In the end, the Chicago 7 were found guilty of some charges, but their convictions were later overturned.

On February 18, 1970, each of the seven defendants was acquitted of conspiracy. Two (Froines and Weiner) were acquitted completely, while the remaining five were convicted of crossing state lines with the intent to incite a riot. On February 20, they were sentenced to five years in prison and fined $5,000 each.

But two years later, on November 21, 1972, all of the convictions were reversed by the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, which deemed that Judge Hoffman had been biased in not permitting defense attorneys to screen prospective jurors for cultural and racial bias. The court also determined that the FBI had bugged the defense lawyers' offices. The Justice Department decided against retrying the case.

The contempt charges were retried before a different judge, who found Dellinger, Rubin, Hoffman, and Kunstler guilty of some of the charges, but did not sentence them with any fines or prison time.

Fifty years later, the Chicago 7 story remains relevant.

In the five decades since those violent days at the Democratic Convention, Abbie Hoffman, Tom Hayden, Jerry Rubin, and David Dillinger have all passed away, while Bobby Seale, Rennie Davis, John Froines and Lee Weiner are still alive. Last August, Weiner published a memoir about his experience.

Last year, with the ongoing protests against police brutality and the public outcry about the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and others—not to mention concerns about the upcoming presidential election— the story of the Chicago 7 and the riots of 1968 felt all too prescient.

The Trial of the Chicago 7 is available on Netflix.

You Might Also Like