The True Story Behind Hamilton: How Much Did The Musical Change?

There's a solid chance you knew very, very little about Alexander Hamilton before he became the subject of a Broadway phenomenon. The story of "the ten-dollar founding father" isn't widely taught, yet it's remarkable for a number of reasons Lin-Manuel Miranda highlights from the show's very first moment: "How does a bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a Scotsman / dropped in the middle of a forgotten spot in the Caribbean / by providence impoverished in squalor / grow up to be a hero and a scholar?" asks the musical's opening number, referencing the fact that Hamilton—in contrast to his fellow founding fathers—was a poor immigrant from the West Indies. As depicted in the show, Hamilton overcame his tragic and inauspicious upbringing and became a political legend in America by "working a lot harder, by being a lot smarter, by being a self-starter."

If you're one of the many, many people who flocked to Disney+ this July 4 weekend to watch the original Broadway production of Hamilton recreated onscreen, A) congrats, you're probably still on a high from the sheer joy of that experience, and B) you may be wondering just how much artistic license the show took with American history. It goes without saying that the style and vernacular of the show is deliberately anachronistic—the soundtrack draws heavily on hip-hop, R&B, pop and other musical genres that were not around in the Revolutionary era, and the characters speak in modern parlance, although their costumes are period-accurate. The show is also peppered with references to real hip-hop history and even modern TV shows like The West Wing.

Nonetheless, Miranda based the show on Ron Chernow's exhaustive 2004 biography of Hamilton, and hews fairly close to historical fact—with a few exceptions. "I felt an enormous responsibility to be as historically accurate as possible, while still telling the most dramatic story possible," Miranda told The Atlantic in 2015. "When I did part from the historical record or take dramatic license, I made sure I was able to defend it to Ron, because I knew that I was going to have to defend it in the real world. None of those choices are made lightly."

Read on for a fact vs. fiction primer on Hamilton.

The casting of Hamilton is historically inaccurate by design.

At risk of stating the obvious, the actual founding fathers were white, while Hamilton reimagines them as men of color, with the roles of Hamilton, Aaron Burr, Thomas Jefferson and more played by Black and Latinx actors. Miranda has described this central innovation as "a way of pulling you into the story and allowing you to leave whatever cultural baggage you have about the founding fathers at the door. We're telling the story of old, dead white men but we're using actors of color, and that makes the story more immediate and more accessible to a contemporary audience."

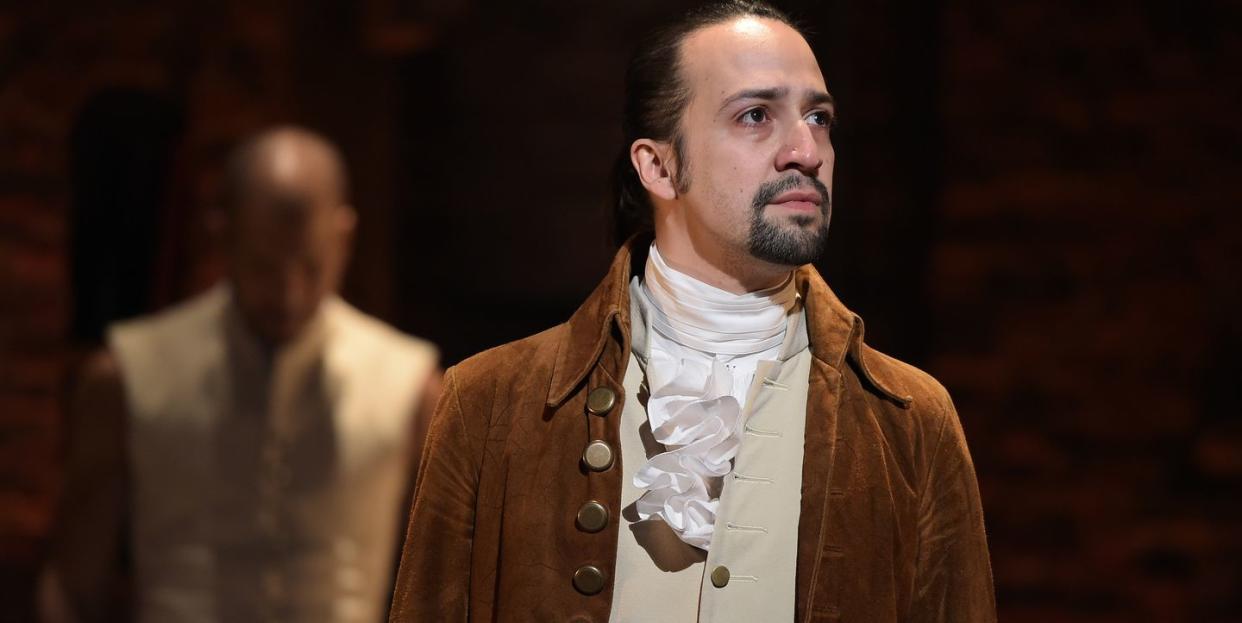

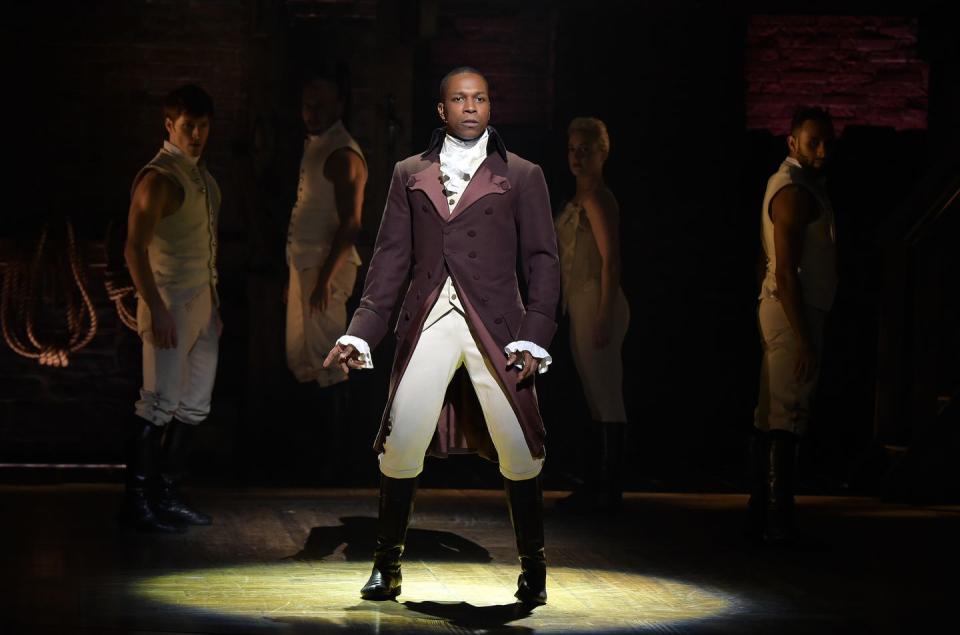

In the original Broadway production, which is the version Disney+ debuted this weekend, Hamilton is played by Miranda, while Aaron Burr is played by Leslie Odom Jr. The cast includes Daveed Diggs as Thomas Jefferson, Christopher Jackson as George Washington, Phillipa Soo as Hamilton's wife Eliza Schuyler, and Renée Elise Goldsberry as her sister Angelica Schuyler.

In reality, all of the named characters in Hamilton were white, with the single exception of Sally Hemings—an enslaved woman with whom Jefferson had a sexual relationship—who appears in a silent cameo. Critics of the show have argued that it erases the presence of real men and women of color during this period of American history. "With a cast dominated by actors of color, the play is nonetheless yet another rendition of the ‘exclusive past,’ with its focus on the deeds of ‘great white men’ and its silencing of the presence and contributions of people of color in the Revolutionary era," wrote history professor Lyra D. Monteiro, in a 2016 essay published in the journal The Public Historian. Later, Monteiro argued, "The idea that this musical 'looks like America looks now' in contrast to 'then'…is misleading and actively erases the presence and role of Black and brown people in Revolutionary America, as well as before and since. America 'then' did look like the people in this play, if you looked outside of the halls of government. This has never been a white nation. The idea that the actors who are performing on stage represent newcomers to this country in any way is insulting."

The love triangle between Hamilton, Eliza, and Angelica is exaggerated but not entirely fictional.

One of the show's standout numbers, "Satisfied," sees Angelica reflecting on the moment she first met Hamilton. She laments that despite their instant and mutual attraction to each other, she can't pursue a relationship with him because he's "penniless" and as the eldest Schuyler sister she has a responsibility to "marry rich." Though Hamilton goes on to marry Angelica's sister Eliza, the two keep up an intimate relationship through letters even after Angelica also marries, and seem to have a deeper intellectual connection than Hamilton and Eliza.

In reality, Angelica was already married with children when she met Hamilton. But their intense connection isn't entirely fictional—Yahoo notes that a large amount of correspondence between Hamilton and Angelica has been preserved, and its playful tone has been deemed flirtatious by some historians. During the show's early run in New York, Miranda tweeted an excerpt from Hamilton and Angelica's real-life letters to each other, noting Hamilton's seemingly pointed use of a comma with the hashtag "#CommaSexting." This is referenced in the song "Take A Break," which finds Angelica over-analyzing Hamilton's punctuation choices in a recent letter to her: "In a letter I received from you two weeks ago / I noticed a comma in the middle of a phrase / It changed the meaning. Did you intend this? / One stroke and you’ve consumed my waking days."

Miranda also took dramatic license with the makeup of the Schuyler family—there were, in fact, three Schuyler brothers, thus negating the musical's line, "My father has no sons so I’m the one / Who has to social climb for one." Miranda addresses this in the musical's companion book Hamilton: The Revolution (via National Geographic): "Okay, so Philip Schuyler had loads of sons. I conveniently forgot that while I was writing this in service of a larger point: Angelica is a world-class intellect in a world that does not allow her to flex it."

Some historians have taken issue with the depiction of Hamilton as an abolitionist.

Although slavery isn't a prominent topic in the musical, some historians say that the show exaggerates Hamilton's "anti-slavery credentials." The most explicit instance comes when Hamilton calls out Jefferson as "a slaver" during their first of two "Cabinet Battle" numbers. During a debate on the founding of a national bank, Jefferson argues that the federal government shouldn't bear responsibility for state debts since the South has none, to which Hamilton responds: "Your debts are paid 'cause you don't pay for labor." And in the closing moments of the show, Hamilton's widow Eliza reflects on how he could have "done so much more" to fight slavery had he lived.

In his book, Chernow depicts Hamilton as an "uncompromising abolitionist," and per The New York Times, historians are divided on whether this is accurate. Hamilton was a founding member of the New York Manumission Society, created in 1785, which pushed for an emancipation law in New York State, and he was publicly critical of Jefferson's racist views. But as historians have noted, Hamilton's father-in-law Philip Schuyler owned slaves, and Hamilton himself may have too.

During an interview with NPR's Fresh Air this week, Miranda addressed the question of slavery within the show. "Hamilton, although he voiced anti-slavery beliefs, remained complicit in the system, and other than calling out Jefferson on his hypocrisy with regard to slavery, doesn't really say much else [in the show]," he noted. "I think that's actually pretty honest. He didn't really do much about it. None of them did enough."

Some critics have also taken issue with other aspects of Hamilton's characterization, suggesting that he was less of a hero than the show depicts. A 2016 New York Times analysis of the musical notes that Hamilton was "an unabashed elitist who liked big banks, mistrusted the masses and at one point called for a monarchal presidency and a Senate that served for life." Writing in The Washington Post at the same time, history professor Nancy Isenberg argued that Burr was actually a much more progressive politician than Hamilton, despite being the show's antagonist. "Burr was in most ways more forward-thinking, by our standards, than his nemesis Hamilton, and the romantic recasting of Hamilton’s life story comes at the expense of a true progressive champion," she wrote.

Hamilton and Burr's complex friendship-turned-rivalry is based on the truth.

One element of Chernow's book that plays out clearly in Hamilton is the idea that Hamilton and Burr lived parallel lives–both were orphans, both served under General George Washington in the Revolutionary War, and both passed the New York bar and set up law practices in the same year, 1782.

But the pair's relationship is exaggerated in the show–for instance, the fictional Burr plays a prominent role in exposing Hamilton's extramarital affair with Maria Reynolds. In the show, Burr, Jefferson and James Madison confront Hamilton with their suspicions that he has engaged in financial fraud, prompting him to instead confess to the affair. In reality, Burr wasn't involved—per Vox, it was House Speaker Frederick Muhlenberg, Rep. Abraham Venable of Virginia, and future President James Monroe who confronted Hamilton.

The musical portrays Hamilton as singlehandedly dooming Burr's presidential run in 1800, when he casts a deciding vote in favor of Burr's opponent, Jefferson. In reality, Hamilton didn't have that kind of influence, although, per PolitiFact, he did lobby the House Federalists to back Jefferson.

Most famously, Burr really did kill Hamilton in a duel (though it happened in 1804, not immediately following the 1800 presidential election). In the show's opening number, Burr foreshadows this grim ending while also making it clear that he regrets the act—"And I'm the damn fool that shot him." In reality, according to Chernow, Burr often referred to Hamilton after his death as "my friend Hamilton — whom I shot."

You Might Also Like