Truck attack in New York turns the spotlight on little-known Uzbekistan

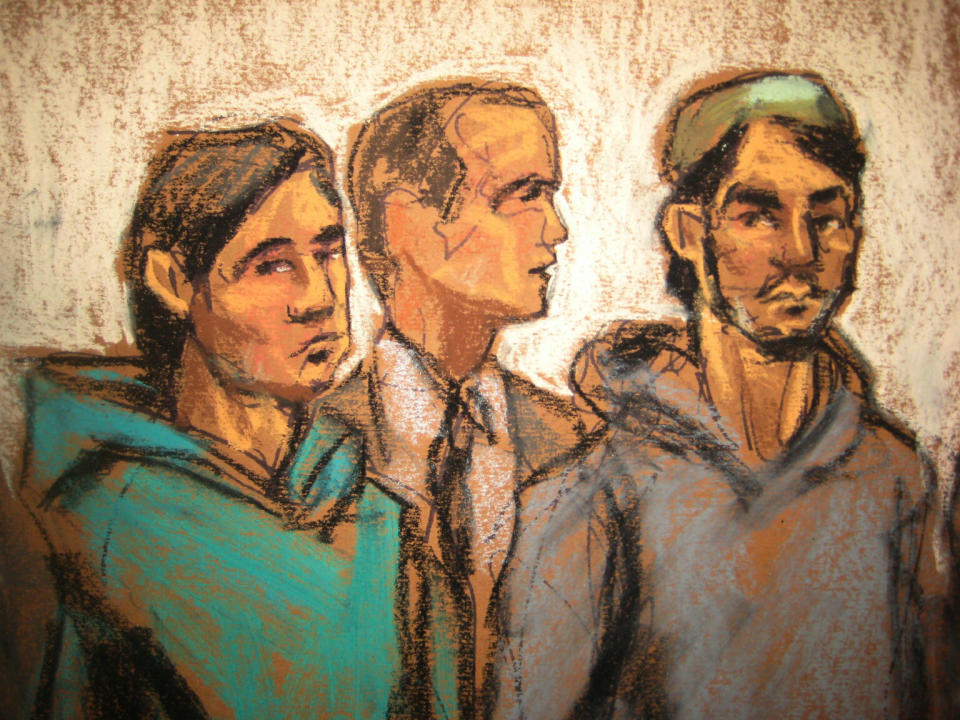

Just a few days before Sayfullo Saipov, a 29-year-old immigrant from Uzbekistan, was arrested in the deadly truck attack on a New York City bicycle path, another Uzbek man was sentenced by a federal judge in Brooklyn to 15 years in prison for conspiring to provide material support to the Islamic terror organization ISIS.

That man, Abdurasul Hasanovich Juraboev, was one of five men from Uzbekistan arrested in Brooklyn since 2015 for conspiring to join the Islamic State. In 2014, Juraboev had threatened online to kill then-President Barack Obama, drawing the FBI’s attention to himself and to two associates — one Uzbek, one from neighboring Kazakhstan — who were charged with plotting to join ISIS fighters in Syria or to carry out violence in the United States, including a plan to bomb Coney Island.

It’s not clear whether Saipov, who had most recently been living in Paterson, N.J., had ties to any of these men specifically. But officials said that Saipov’s name had surfaced in a separate investigation before Tuesday’s attack, in which he allegedly drove a truck for nearly a mile down a riverfront bicycle path, killing eight and injuring 11 before he was shot and captured by police. By Wednesday evening, federal agents had located a second Uzbek man, 32-year-old Mukhammadzoir Kadirov, who they believe had been in contact with Saipov.

The dust had barely settled on the West Side Highway before President Trump began reigniting his push for tougher restrictions on immigration and even travel to the U.S. as a way to keep out terrorists. Uzbekistan has never been mentioned by Trump as a potential threat and was not listed in any of the several versions of the administration’s travel bans. But natives of the former Soviet republic, which borders on Kazakhstan, Afghanistan and other central Asian countries, are very much on the radar of security officials in other countries. Uzbek nationals have been accused in a number of violent attacks in the name of ISIS, including the New Year’s Eve shooting at a nightclub in Istanbul that killed 39 and a truck attack in Stockholm this April that left five people dead and several others injured. Authorities in Turkey have identified citizens of Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan among those responsible for the deadly attack on Istanbul Ataturk Airport in 2016.

“We cannot say for sure when or where these individuals were radicalized, but what makes Islamic State different from groups like al-Qaida or the Taliban is its ability to reach potential recruits in their native language, be that Russian or Uzbek, [and] whether they are living in Central Asia, Russia, Europe or the U.S.,” Deirdre Tynan, Central Asia project director for the International Crisis Group, told Yahoo News. “These are accessible, slick and well-produced campaigns across a range of platforms. Recruiters and others interested in Islamic State can communicate online creating a sense of community and purpose that can be compelling and very difficult for the authorities to take action on.”

In recent years, the Islamic State’s sophisticated recruitment campaign seems have had notable success in penetrating the fringes of Uzbekistan’s Muslim majority. But Islamic extremism is endemic in the nation, whose autocratic government has long been condemned by international human rights groups for systemic religious persecution, even codifying restrictions on religious freedom into the national law.

In fact, Erica Marat, associate professor and director of the Homeland Defense Fellowship Program at National Defense University, said that radical Islam’s presence on the fringes of Uzbek society predates the country’s independence from the former Soviet Union in 1991.

“Inside Uzbekistan, it’s always been a way of political protest to an oppressive government,” said Marat, an expert on security issues in post-Communist countries. Under officially atheist Soviet rule, “the government always made it worse by trying to control religious expressions, and presenting itself as the only legitimate power.”

Although they constitute an overwhelming majority of the country’s population, Muslims have long been targets of religious persecution at the hands of the Uzbek government. In 2004, Human Rights Watch reported that, over the previous decade, the government’s persecution of Muslims who don’t align with an officially authorized branch of the faith had “resulted in the arrest, torture, public degradation, and incarceration in grossly inhumane conditions of an estimated 7,000 people.”

Resentment against the oppressive government, run by President Islam Karimov from 1989 until his death in 2016, led to the emergence in 1998 of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, or IMU, a militant Islamist group aimed at overthrowing Karimov. In more recent years, however, the IMU has expanded its purview beyond Uzbekistan’s landlocked borders, allying itself first with al-Qaida and the Taliban, and eventually with the Islamic State. In 2015, the IMU’s leadership announced that the Uzbek group was not just an ally, but actually a part of ISIS.

According to an October 2017 report by the Soufan Center, a nonprofit focused on global security research, ISIS has recruited an estimated 1,500 soldiers from Uzbekistan to fight in Syria or Iraq.

In addition to the desire for freedom of religious expression, Marat points to the economic opportunities provided by ISIS as a major selling point for some financially frustrated Muslims in Uzbekistan and the surrounding region.

“Fighters joining from Central Asia are also known to be attracted to ISIS precisely as a way of earning a living,” she told Yahoo News.

Still, while Marat said that Uzbekistan is certainly among the places that have seen an increase in radicalization and support for ISIS, she emphasized that Islamic extremism is still very much confined to the country’s political fringe.

“It’s important to know that there are far more people living in Uzbekistan and the wider region that condemn extremism,” she said.

Marat also cautioned against conflating the growing allure of ISIS in Uzbekistan (and in Central Asia generally) with the radicalization of Saipov, who has lived in the United States since 2010.

“These are two parallel processes, as I see them,” she said, suggesting that while Saipov may have been exposed to militancy in Uzbekistan, “I think his radicalization could have really taken place here in the U.S.”

News stories since Saipov’s arrest are consistent with that view.

“Unfortunately, this is a common story for migrants from different regions, coming from countries where community support and large families really help you to succeed in life, the Western experience of relying on your own work, your own effort is a bit of a shock,” she said. “Some people are able to flourish in this Western environment. Others, however, get frustrated and feel that they’re failures because they’re unable to live their American dream or whatever they believe the West to be.

“ISIS, with its larger-than-life ideology, offers this venue for young men and some women to feel like they belong, to regain some sense of community,” she said.

What ultimately led to Saipov’s radicalization is not yet clear, but according to court documents outlining the federal charges filed against him Wednesday, he told investigators that he’d been planning to carry out an attack for a year and had been inspired to do so by watching ISIS videos on his cellphone, particularly one in which ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi called on Muslims living in the United States to retaliate for Muslims killed in Iraq.

As the case against Saipov moves forward, Marat said, “it’s really important to understand the specific moments in the life of this attacker that led him to radicalize, what is it in his behavior, the challenges that he faced.”

“I’m not trying to defend him,” she clarified, but understanding “his grievances, his perception of life in the U.S., would really help us understand why individuals, especially from Muslim countries, are radicalized in the U.S.”

“I think, in this sense, ethnicity, or place of birth, is a poor predictor,” Marat continued. “It’s more about what are the experiences that immigrants live in the U.S.”

Read more from Yahoo News: