The Tragic Last Days of Movie Mogul Steve Bing

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It was late June, and Steve Bing wasn’t picking up his phone. This wasn’t all that unusual. The movie producer and real estate heir was known to disappear at times, usually without warning. Only his closest friends knew where he went, and why he frequently changed his number.

He was weathering the lockdown at the hottest address in Los Angeles, the Ten Thousand Building in Century City, where a 4,000-square-foot penthouse costs $65,000 a month, and the isolation was bringing deep-seated anxieties into sharp relief.

Back in the 1990s Bing had cultivated a Jay Gatsby–esque image in Hollywood, dating supermodels and starlets, most famously Elizabeth Hurley. At six-foot-four, he had the lanky build of an athlete, but he was quiet and elusive, and he took great pains to downplay the $600 million fortune he had inherited from the family business, Bing & Bing, a New York real estate development firm that had become one of the most successful of the early 20th century. He once imagined he would dominate the film industry like a modern-day Howard Hughes, but things hadn’t gone according to plan.

He was 55 years old, and most of the films he had produced had flopped, including the Hughes biopic Rules Don’t Apply, starring, written by, and directed by Warren Beatty, one of several octogenarians, alongside James Caan and Jerry Lee Lewis, Bing admired and befriended. The L.A. he and his cohort romanticized was gone, and for days texts from worried friends went unanswered. They feared he was in a downward spiral. By the evening of June 22, most of Bing’s inner circle, including Bill Clinton and Mick Jagger, had heard the news: Just after 1 p.m. Bing had leaped to his death from his apartment balcony.

“I loved Steve Bing very much,” Clinton tweeted that night. “He had a big heart, and he was willing to do anything he could for the people and causes he believed in. I will miss him and his enthusiasm more than I can say.”

Within hours conspiracy theories were circulating on the internet that Bing had not killed himself but had been murdered because of his connection to the late multimillionaire sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. Friends found this absurd, even offensive—the two never met, close associates say—and they speculated that loneliness had pushed him over the edge. Few knew the truth: that Steve Bing feared he was on the brink of financial ruin, and that long-buried secrets were catching up to him. By the time of his death, bad bets, unpaid bills, and wrong choices had left him with next to nothing.

ONCE UPON A TIME…IN HOLLYWOOD

Steve Bing stepped outside his house in Bel Air and looked out toward the ocean. It was 1993. “Where do you want to go to lunch?” he asked his friend Josh Chrisant, an interior designer 14 years Bing’s senior.

“I don’t care,” Chrisant tells T&C he replied. “I’m easy.”

“Well, I just inherited $600 million last night, so…” Bing looked at Chrisant and grinned.

Everyone who knew Bing back then has similar stories. Carrie Mitchum, the granddaughter of Hollywood icon Robert Mitchum, remembers meeting Bing at Trader Vic’s in the ’80s. He was hanging out with members of the Brat Pack—Emilio Estevez and Rob Lowe—but Mitchum didn’t know that Bing came from money until he invited her to a pool party at his parents’ house on Alpine Drive, not far from where Charlie Chaplin had once lived.

“They had this gorgeous house overlooking all of L.A., and I was shocked, because he just wore khakis and jeans and tennis shoes and drove an old car,” Mitchum tells T&C. “He was such a change from most people in L.A., because there wasn’t anything flashy about him. I guess the term is extremely humble.”

The Bings were as close as L.A. got to old money. His grandfather Leo S. Bing built some of the most famous apartment buildings on Manhattan’s Upper East Side and amassed a fortune of more than a billion dollars before his death in 1956. When Steve was three, his father Peter, a doctor who had served in public health under presidents Kennedy and Johnson, moved the family to Beverly Hills. Even though they were on the Forbes list of the 400 richest Americans, Peter drilled into his children the importance of modesty. They flew coach and drove beat-up station wagons.

Steve got straight A’s at Harvard-Westlake, one of L.A.’s most prestigious private schools, and sold his first screenplay while still there, but his adolescence was marked by a complicated relationship with his father. Steve, who slept in a guesthouse on the family compound, called himself an orphan.

Bing found surrogate fathers in movie veterans like the director Garry Marshall and Caan, who persuaded him to coach his son’s T-ball team. Bing went on to Stanford, where his father, an alum, was on the board of trustees and had endowed a building named after the family, but by his junior year he had dropped out to pursue filmmaking full-time.

“He was a bit of a whiz kid, and good-looking,” recalls the longtime entertainment journalist Lynn Hirschberg. “He liked old Hollywood. If you grow up somewhere else, it doesn’t matter to you. But if you grow up in L.A. it matters. It means something, and he wanted to be part of that world.”

By the late ’80s Bing had developed a reputation as a womanizer, much like the men he had grown up idolizing. He was prone to categorizing the women in his life—the girl you call at 2 a.m., the girl you take to an event. “You never know,” he liked to tell friends, quoting Beatty to explain why he’d sleep with just about anyone. “She may be the best fuck of your life.”

Heidi Fleiss, the infamous Hollywood madam and, later, convict, recalls meeting Bing when he was 22 at a party at the Mondrian Hotel.

“The balance was always off at my house, heavier on the girls’ side. So I’d call Steve and have him bring some guys over,” she says.

Every once in a while, Fleiss says, Steve would call and ask her to send over one of her charges, even though he insisted he was never her client. Once, according to Fleiss, one of her women came back and told her she’d seen drugs in Bing’s bathroom. “And I was so adamant. I said, ‘You’re a liar. You don’t even know who this person is. He would never do drugs,’ ” Fleiss says. “To me, Steve was so pure and sophisticated. I was positive he didn’t do drugs. I had no idea.”

THE BAD BOY & THE BEAUTIFUL

In 2000 Bing formed a production company called Shangri-la Entertainment and scored an eight-picture deal with Warner Bros. He also co-wrote what became a hot screenplay with his buddy Scott Rosenberg, who had established himself as a buzzy screenwriter with the action hit Con Air. Their pitch sparked a major bidding war, and it garnered Bing and Rosenberg a $1.4 million payday from Jerry Bruckheimer.

“Part of what happens in Hollywood is that if you are sincere, truly sincere, and energetic and happy about what you’re doing—and the stars align—sometimes good things happen,” Chrisant says. “In the beginning, at least, he was optimistic about everything he did.”

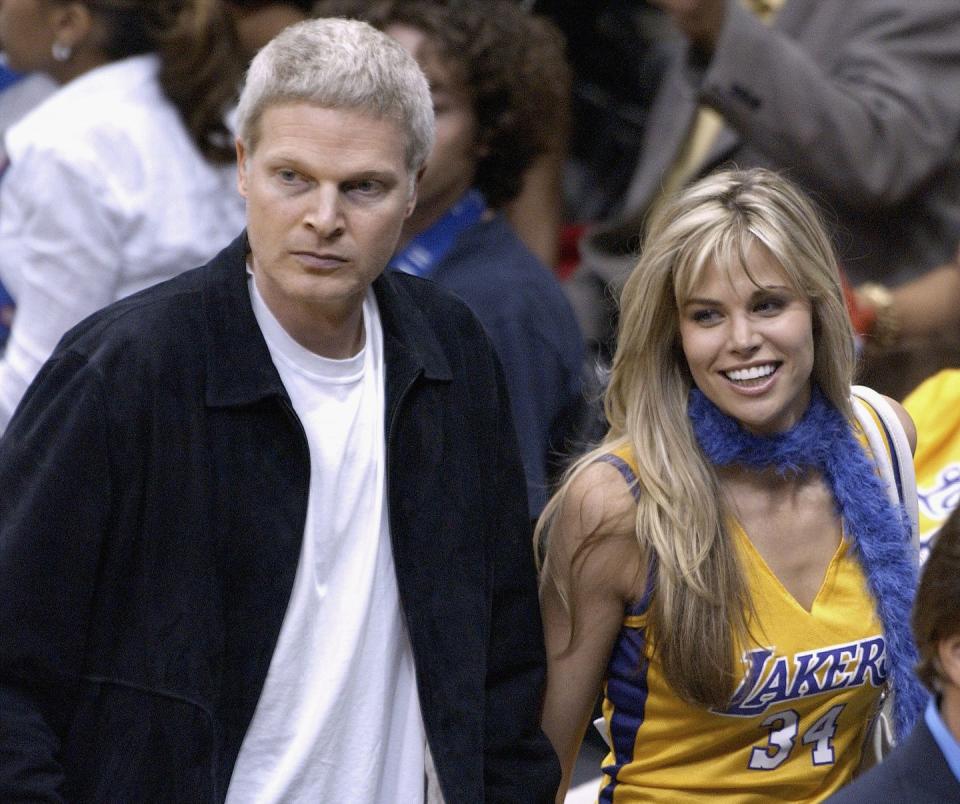

Around the same time, Bing met the model and actress Elizabeth Hurley, who was then the face of Estée Lauder. Bing didn’t seem like the average L.A. producer. “He wasn’t douchey,” says a Hollywood agent who knew Bing for more than 20 years. “He might have been out the night before partying with Charlie Sheen, but he never talked about it.” Hurley was charmed by Bing’s nerdiness—he had just finished the first volume of Robert Caro’s biography of Lyndon Johnson—and his passion for the environment and liberal causes. He was also a cinephile: Twice a week he rented out a Beverly Hills screening room and showed old films to his friends.

Bing had not given up what one of his friends called his “decadent bad boy life”—there were frequent trips to Vegas strip clubs, and an affair with an Armani model while he and Hurley were together—but he had fallen for Hurley, and he wrote love letters, bought her a sapphire and diamond ring, and flew her around the world on his private jet.

In the late summer of 2001, Hurley called Bing to tell him she was pregnant and planned to keep the child. He asked her to fly to L.A. to discuss it and, once she arrived, he reportedly advised her to get an abortion. She flew back to London, and they soon split up.

In November, Hurley announced to the public that she was pregnant. A month later, when she went on NBC’s Today show and identified Bing as the father, he was incensed. He had always carefully guarded his privacy, and now there were pictures splashed across the tabloids. He issued a terse press release saying they had been in a non-exclusive relationship and that it was “her choice to be a single mother.”

The London papers pounced, calling him "Bing Laden." Two months later the New York Post was proclaiming him “the Sperminator,” after a private investigator proved that Bing had fathered a baby girl four years earlier with Lisa Kerkorian, the ex-wife of the Las Vegas casino magnate Kirk Kerkorian.

Humiliated and hurt, Bing poured himself into philanthropy. In 2001 he quietly pledged $10 million to the Natural Resources Defense Council; the next year he wrote a $5 million check to the Democratic National Committee, then the second-largest such donation ever. In 2006 he singlehandedly bankrolled a California ballot measure that aimed to raise $4 billion in oil production taxes. And over time he gave more than $10 million to the Clinton Foundation.

He also started a record company and a construction company, he bought real estate, and he spent lavishly on producing films—$63 million for Sylvester Stallone’s Get Carter and $100 million for a pair of risky animated movies by Robert Zemeckis—but too many were expensive flops. That comedy that had once triggered a bidding war? Kangaroo Jack was savaged by critics and ultimately eked out only a modest profit. Hollywood increasingly saw him as a dilettante with a checkbook, and by the end of the decade he was an aging playboy, his appetite for younger women a punchline. In 2008, Gawker named Bing part of Clinton’s Billionaire Boys Club, which included Ron Burkle and Jeffrey Epstein.

“He was definitely in this circle of dudes who were hitting the clubs and were too old to be doing it,” says an agent who worked with Bing and represented some of his friends. “You’re in your mid-forties and you’re hitting Tao three times a week? There’s something slightly pathetic about that.”

Friends like Chrisant, who designed the interior of Bing’s Boeing 737, saw him frequently. “He loved to drive, especially in the desert,” he says. “We’d drive for 10 hours and just talk and giggle and share stories. And then he’d go back into the real world where he had to live.”

So did Fleiss, who was becoming a supporting player in a rather familiar plot. She became concerned when Bing’s depression led him to crystal meth, and three years ago she realized something was up when they were staying at the Beverly Hills Hotel. “When I saw his arms, I said to him, ‘Oh no, Steve, you’re over. It’s done.’ My heart just sank. I don’t know anyone who comes back from that,” she says.

Last winter Fleiss was in L.A. and wanted to meet up with Bing. When she couldn’t get hold of him for several days, she called around, panicked that he might have overdosed. He was fine. Embarrassed, she apologized for raising the alarm. He told her there was no need. His circle of friends might include a former president and some of the richest men in California, but he was happy that there was someone looking after him.

TWO LOST SOULS IN BEVERLY HILLS

In June 2018 Carrie Mitchum met Bing for dinner at Mr. Lyons, a popular steakhouse in Palm Springs. They had known each other since their twenties, and he worshiped her grandfather. He had once said his most prized possession was a framed note, on stationery from the Four Seasons Hotel, letting him know that Robert Mitchum would join him for lunch, a meeting arranged by his girlfriend at the time, Sharon Stone. Bing told friends that if his house burned down the note was the only thing he’d save.

That night Carrie’s niece Allexanne Mitchum joined them. She was 27, younger than Bing by 26 years, but she was an artist and had an ethereal, new age vibe he found intriguing. Despite the age difference he saw in her a kindred spirit, and soon the unlikely couple were inseparable. A child of actors, she had also suffered a bittersweet upbringing, and she shared his cynical view of Hollywood.

They talked about getting out of L.A. and starting a family together. Bing rented a house for them in Palm Springs and promised to build Allexanne an art studio. For the first time in his life, he was cooking meals at home and eagerly talking about having another child.

Then, in June 2019, while they were staying at a hotel in Beverly Hills, the couple had a fight, and Bing asked her to spend the night elsewhere. Allexanne went to a friend’s house, and 24 hours later she was in a coma at a UCLA hospital from a drug overdose. She died eight days later.

Bing became convinced that her death had not been an accident, and Carrie Mitchum says she got calls from him in the middle of the night asking her if she had learned anything new from the hospital or the detectives investigating her death. Even after the death was ruled an accidental overdose from taking Xanax with fentanyl, Bing kept calling. “He started asking me if I believed in the afterlife,” Mitchum says. “Did I have dreams about her? And if so, what did she say to me? I think it really shook him.”

Last August, Bing summoned a confidant who managed his finances to meet him at the Beverly Hills Hotel. The person, who agreed to speak on condition of anonymity, found Bing feeling regretful, in bed with the lights off and the curtains drawn, after several days of drug use. He had made strides in a two-year effort to reconnect with his daughter Kira Kerkorian, now a grown woman studying public affairs at UCLA, but substance abuse had again gotten the best of him, and he had begun blowing off dinners. Eventually she stopped taking his calls.

Bing asked for help with killing himself, but the friend managed to talk him down, and instead they went down the street for a steak dinner, which Bing devoured. “He looks at me and he goes, ‘I guess it’s a good thing I’m alive. Maybe I shouldn’t kill myself,’ ” the friend says. Shortly thereafter, Bing agreed to enter rehab.

FADE TO BLACK

A month before Bing died, Carrie Mitchum paid him a visit and found his 27th floor palace mostly empty. They sat across from each other eating macaroni, and Bing asked her if she believed in God. “You know what? It doesn’t matter,” she recalls him saying. “You can believe in God or not and the result is the same. It’s irrelevant.”

“I felt like he needed answers I didn’t have,” Mitchum says. Bing was speaking to a therapist twice a day, and he had been sober for several months. A dispute with his father over a trust for Bing’s children had left him bruised, but it had also led to his reconnecting with Hurley and their son Damian, a budding model.

A post shared by Elizabeth Hurley (@elizabethhurley1) on Jun 23, 2020 at 3:03am PDT

Contrary to press reports, Bing did not leave a suicide note. The morgue contacted Kira to make funeral arrangements, but in the end it was Peter Bing who claimed the remains of his son. Per his wishes, Steve was laid to rest in Santa Monica in a green cemetery with a petrified wood headstone.

In September a judge in L.A. ruled that Kira would administer what little remained of his monumental birthright. Only about $300,000 is left in liquid assets, which was meant to be bequeathed to the Clinton Foundation, and that’s before debts are settled. Relative to the extraordinary estate he inherited in his youth, Bing was broke.

“There were two of him,” says a former lover. “He could be charming, generous, kind, the life of the party, but at the end of the day he went home alone. He was a very lonely guy.”

In the end, the most gripping production Steve Bing ever financed was his own life. Perhaps it was the one script that had gone according to plan, an L.A. story filled with the film noir themes he loved: the corrosive toll of wealth, the strange alliance between celebrity and decadence, the solitude that settles upon a man stripped of power and riches.

“He realized he purchased everything. Every person, every opportunity, every glorious moment,” Chrisant says. “The tragedy is he needn’t have.”

This story appears in the November 2020 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like