'It took a long time to get here': behind the National Museum of African American Music

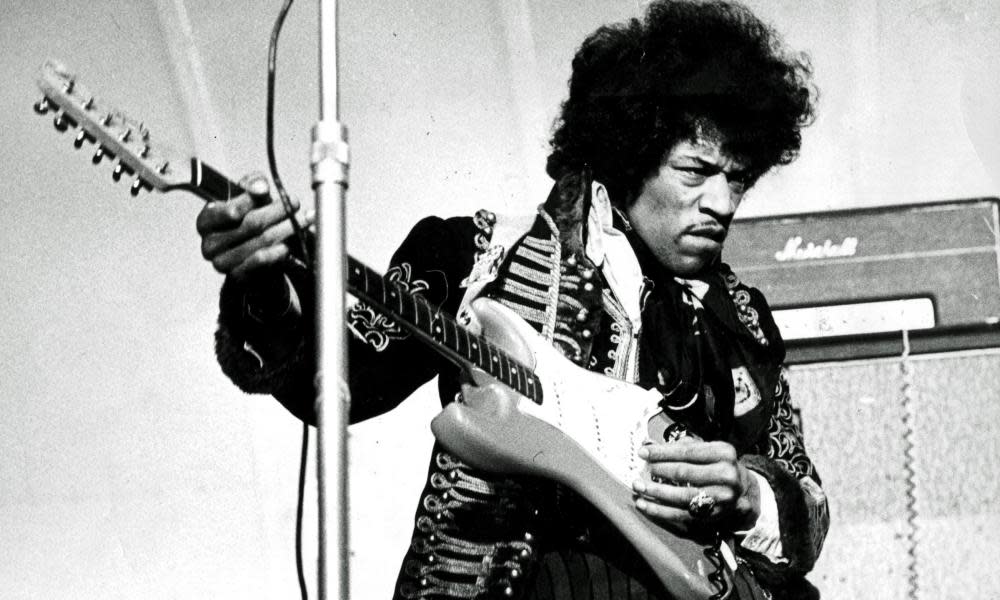

In 1967, Jimi Hendrix accidentally cracked his guitar before a concert. Seeing it was pretty much broken, he decided to destroy it on stage.

When he did, the audience went wild.

Destroying guitars became a regular part of his act. Hendrix destroyed dozens of guitars over his career and one that was salvaged and saved can now be seen in Nashville.

Related: 'All they want is my voice': the real story of 'Mother of the Blues' Ma Rainey

The guitar is on view at the new National Museum of African American Music, which opened on Martin Luther King Jr Day. Tracing over 400 years of black music, from gospel to jazz and R&B, it pays long overdue tributes to musicians like Ma Rainey and Sister Rosetta Tharpe, among others.

Over 1,500 items are in the collection, from Hendrix’s guitar, to Whitney Houston’s outfits, Ella Fitzgerald’s coat, vintage photos, mixtapes and LPs in the 56,000-sq-ft museum. “We say that black music now has a home,” said the museum’s president and chief executive Henry Beecher Hicks III.

“We didn’t feel like there was a cultural institution on a national scale that celebrated African American contributions to American music,” he added. “There are places that deal with a label, a genre or an artist, but no place that really tells the story of how rich and robust this tradition really is.”

The museum is divided into seven sections, from jazz to gospel to hip-hop. There is rare memorabilia, personal artifacts and state-of-the-art technology to tell the story of African American music and history, which is both celebrated and preserved.

It all started 23 years ago when Hicks and his team conceived the idea of the museum. “It took a long time to get here,” he said. “It was a lot of twists and turns; three location changes, a flood, a tornado, two recessions, a pandemic, all of it.”

The initial vision of the museum has stayed the same since 1998. “Civil rights, art, culture and sports are all the context for where the music came from,” he said. “It’s giving credit where credit is due, recognizing this idea that American music is African American music.”

There is one section devoted to African American music traditions called the Rivers of Rhythm Pathways. “It features artists whose names we know and don’t know,” said Hicks. “It’s not just who they are but how it’s all so connected. All music is connected; genre is a commercial creation.”

Another section in the museum is called Wade in the Water, which traces the roots of gospel music. “When Africans were brought here, they were forced to leave their culture behind, so they had to innovate,” said Hicks. “That innovation is what we now know as American music.”

In the Crossroads section, we see the roots of 19th century blues, while a section called A Love Supreme looks at the Harlem Renaissance and the birth of jazz.

The museum also looks at how the civil rights movement and music were closely intertwined. In a section called The Message, it shows the origins of hip-hop in the 1970s.

Among the long overdue tributes, there is a video devoted to the Nashville Super Choir, which is led by Bobby Jones (many people might think of Nashville as purely a country music capital, but it’s also a hub of gospel).

There’s also a tribute to Tharpe, a queer black woman who trail-blazed rock’n’roll in the 1930s and 40s and influenced Chuck Berry and Little Richard (she was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2018). “We’ve made it a point to highlight women in a way that is more than they are typically in the music industry,” said Hicks, “to make sure their stories are prominently told”.

In the Crossroads section, which traces music from the late 19th century in the deep south, there are photos of blues musicians Gary Clark Jr, BB King and Bessie Smith, and educational information on instruments like the diddley bow, a single-stringed instrument which was integral to the development of blues music.

There’s a photo of Clifton Chenier, a Grammy Award-winning musician from Louisiana who played the accordion (and spelled his name out in tape on his instrument) and toured with Etta James.

On one wall, there’s a quote from Harry Pace, the first African American to own a record label, Black Swan Records. Pace once said: “Companies would not entertain any thought of recording a colored musician, or colored voice. I therefore decided to form my own company and make such recordings as I believed would sell.”

There’s also a quote from Elvis Presley citing the influence of African American musicians on his own music. “The colored folks been singing it and playing just like I’m doing now, man for more years than I know,” said Presley, who cited Delta blues singer and guitarist Arthur Crudup as a key influence. Today, Crudup is credited as “the father of rock’n’roll”.

There are touch screens that reveal how demos were turned into hit songs, old LPs hanging on the walls and posters advertising concerts from half a century ago.

In the hip-hop section, called The Message, there are photos of New York City in the 1970s, graffiti and breakdancing. In one quote from hip-hop founder DJ Kool Herc, he says: “To me, hip-hop says, ‘Come as you are.’ We are a family; it’s about you and me, connecting one to one. It has given young people a way to understand their world, whether they are from the suburbs or the city, or wherever.”

The section highlights talents from the golden age of rap, the 1990s, with photos of Queen Latifah, LL Cool J, Jay-Z, The Fugees, the Notorious BIG, Tupac Shakur and – even though they’re not African American – the Beastie Boys. This section features glass boxes of rappers on the cover of the Source magazine, LP album covers, gold rap bling, bucket hats and mixtapes. Beyoncé and Kendrick Lamar are featured too, but this section ends in 2010.

“It was the hardest story to tell – most of us have lived hip-hop,” said Hicks. “Its significance is still being shaped; the story is still incomplete. We tried to be protective of drawing lines that have enough distance from the topic to make room for historical perspective.”

Among the valuable objects on view, there is an old trombone played by a Mississippi-born jazz musician Helen Wood Jones. She performed in the International Sweethearts of Rhythm, the first all-women’s band in the country, which was founded in 1937.

“She was a pioneering woman, very notable,” said Hicks. “She ran away from home as a teenager, she wanted to sing jazz and joined this all-female multi-racial jazz band.”

Hendrix’s destroyed guitar was from the collection of photojournalist George Tillman (who obtained it from Larry Lee, a guitarist who worked with Hendrix).

“This guitar provides a physical reminder of the power of his music, his personality and his brand of self-expression that was as influential in the 1960s as it is today,” said the museum’s curator, Steven Lewis.

There is also a faux leopard skin jacket that was once worn by Ella Fitzgerald, a pair of Converse sneakers that belonged to DJ Kool Herc and the last outfit worn onstage by Grammy Award-winning TLC rapper Lisa Left Eye Lopez before she passed away in 2002.

“It tells a compelling story,” said Hicks, a former investment banker and White House fellow under the Clinton administration.

Beyond the artifacts, the technology is meant to show both sides of the coin.

“We combine the artifacts with the technology so you get what music is and can be,” he said. “It takes you back to see the history of music, but the technology lets you go forward and see the future.”