Tony Duquette's Home and Studio From 1965 is Still Serving Major Decor Inspo

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

For House Beautiful’s 125th anniversary this year, we're rewinding time by exploring the best spaces from our archive—including, so far, decorator Sister Parish’s New York Apartment, and the timeless appeal of skirted furniture. Next up, we’re visiting the West Hollywood home and studio of designer extraordinaire Tony Duquette, as seen in a 12-page spread first published in our June 1965 issue, where we dubbed it "the house of a magician."

To truly grasp the significance of—and explore the history behind—the former residence of one of the design world’s greatest visionaries, we spoke to Hutton Wilkinson, who worked alongside Duquette on both interior and jewelry projects for nearly five decades. He now serves as the president of the Anthony and Elizabeth Duquette Foundation for the Living Arts, which is, in part, committed to preserving the legacy of Tony Duquette.

Located at 824 North Robertson Boulevard in West Hollywood, the studio (not to be confused with Dawnridge, the late designer’s former Beverly Hills residence, which recently played a starring role in Netflix’s Ratched) was never meant to be a residential structure, but that didn't deter Duquette, who lived there with his wife for 40 years.

“The living room was 150 feet long, 28 feet wide, and 28 feet tall, and Tony built a stage at the end of the room to display costumes and sets, which he also used for orchestras to play at parties," recalls Wilkinson.

Built in 1921, the property is now a movie production office—which, in a way, pays tribute to the dwelling’s origins, given that it was built at the request of Joseph Michael Schenck, a Russian-American film studio executive who co-founded Twentieth Century Pictures now 20th Century Fox). You might not recognize him by name, but Schenck’s influence on Hollywood is still discernible to this day: He helped launch the career of Marilyn Monroe by persuading his friend—then-production director of Columbia Pictures, Harry Cohn—to sign a deal with her in 1948. Schenck had the structure built as a studio for his wife, Norma Talmadge, who was a successful silent film-era actress and producer.

The area surrounding the property was once Talmadge’s back lot—and her former dressing rooms are now part of a duplex apartment located just around the corner, on the aptly-named street Norma Place.

After Talmadge’s studio was no more, the property acted as a theater for the road company of the 1925 film The Merry Widow (which features uncredited appearances by pre-fame Joan Crawford and Clark Gable). Not long after, the studio-turned-theater took on its least glamorous role yet: serving as the production site of a water bottle company that claimed to sell mineral water. After it was discovered that the water actually came from a nearby reservoir in Los Angeles, says Wilkinson, the company wasn't long for this world.

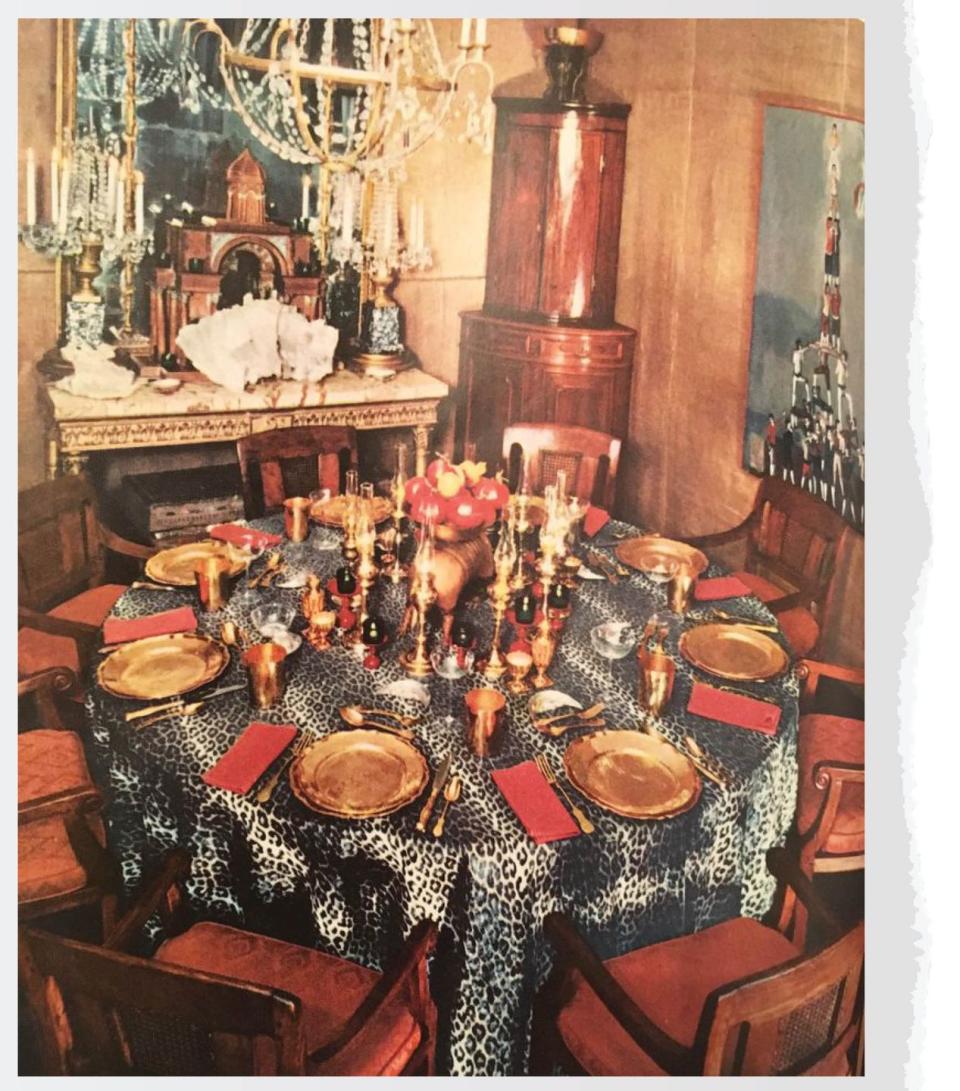

Finally, in 1950, the historic building—and eventually, the entire block—was purchased by Tony Duquette, who would soon restore and transform the structure into what graced the pages of House Beautiful 56 years ago. True to his maximalist reputation, the designer filled the unconventional space with all manner of theatrical accessories, like brass palm plants, wall-hung elk antlers, lush red carpets, nacre obelisks, and towering decorative screens. He set the table with animal-print textiles for fabulous dinner parties, lit the gardens with Moroccan lanterns, and, as the original article notes "sometimes called a ballet troupe" to entertain during dinner.

Read the original story below:

Here Enter The House of a Magician

A splendid enclave of, on occasion, great entertainment; where paintings are painted, costumes sewn, chandeliers strung, jewels set, and hardly any fantasy or beauty is beyond achievement.

The wall is high. The gate massive. Outside is the giant, Los Angeles. Inside is a thicket of fragrant mock orange lighted with fireflies and ancient Moroccan lanterns. The step is red carpet. And the escutcheon doors have weathered four hundred years of Spanish rain and sun. Here live the Duquettes. Here they work. Entertain. Maintain an almost Renaissance atelier. The concept and the actuality is, in fact, out of time and out of space. The possessions of this house, as you will see, have been summoned, like the ghost of Hamlet’s father, out of the regal magnificent past and from the kingdom of the sea, the jungle, the forest, and the sky. The accomplishments are cerebral, aerial, romantic, benign, and full of the power of wonder and amazement. This place began as a movie studio, when stars had their own domain. This was Norma Talmadge’s. And the 28-foot ceiling reached up to encompass her cameramen, booms, and lights. It now hardly accommodates the lofty reach of Duquette mirror and antler. The house has been designed so that every chest, trunk, and box holds a compatible treasure; every door opens a view more beautiful than the immediate scene. And so they do. On the other side of the great door, the salon. Here Tony and Beagle Duquette entertain. The stage, set with obelisks of nacre, is where sequences of costume for the ballet, the stage, and films—designed by Tony Duquette—are shown; where, on occasion, visual auditions for “angels” are staged; where a small ballet troupe is sometimes called for a dinner party. The salon itself is wide enough, polished enough, and dazzling enough for many an enchanting private ball. Dinner! What would you do if you were a magician and had eight for dinner? You’d clap your hands and produce the vermeil plates and goblets on a leopard cloth, wouldn’t you? And Baccarat crystal. For a centerpiece...pomegranates riding on a gold-plated armadillo. Now, besides a really sparkling chandelier, you’d convert the whale-oil lamps to kerosene. And the chairs? Only the English Planter’s chairs from Siam. That’s about it (except, of course, the menu). Additional enchantments to be seen, left: The Italian console holds a 17th-century model of a basilica, a crystal candelabra, and a hillock of rock crystal. Painting is 18th-century Venetian, “The Gondolieri.” Look above at the storied parade sketched for M.G.M.’s Kismet. Across the page at the brilliantly costumed figures for Everyman, which was staged year after year before the cathedral at the Salzburg Festival. Glance at the coffee table and see the petrified turtle with the liquid-gold articulated snake and a tiny figure astride an ermine. Here is the condensed signature of Duquette. Where has this earthly-unearthly genius come from? The influence is neither Dali nor Max Ernst. More truly the impressions of a boy, born in California, thrust into the sharply changing wonders of winter, spring, summer, and fall in northern Three Rivers, Michigan—who loved the dark woods, the streams, the lakes, and who probably went whistling home with a toad in his pocket to feed his jar of fireflies that was propping up his copy of Alice in Wonderland. His formal art schooling was pure Bauhaus, which must have slipped off like an untied shoe. Far back in his consciousness may have been the proud memory of his great-uncle Marshall, partner of the pre-Raphaelite storm center, William Morris, and in the rising background shine Lady Mendl and Frances Elkins. The Duquettes (she was Elizabeth Johnson from Los Angeles) went to art school together, where she painted figures, birds, and animals “beautifully.” She paints now, with skill and authority, mostly figures wrapt in a distant bewitchment. The activities of Tony Duquette are so multiple they are hard to record. Most recently the curtain in the new music center in Los Angeles and the costumes for Salome. But his works include the triumphant costumes for Broadway’s Camelot, half a dozen ballets, half a dozen more movies. And one-man shows in the Pavillon de Marson, the Louvre, and six museums in this country.

Follow House Beautiful on Instagram.

You Might Also Like