It's Time to Buckle Up for a Bumpy Election

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“Is something going to happen on Election Day?” asked Sen. Ron Johnson at a recent campaign stop in Wisconsin. “Do Democrats have something up their sleeves?” In September, the senator refused to commit to accepting the results of the midterms next week.

“Kari Lake is very dangerous for our country,” runs a campaign ad targeting the woman running to be governor of Arizona. The speaker is the mother of a Capitol Police officer who died a day after confronting the pro-Trump mob at the Capitol on January 6.

A Democratic candidate for the Pennsylvania House of Representatives reported being attacked this week in his backyard. “He hit me 10 to 12 times in the head, in the face and by the eye and he knocked me out.”

This is not an ordinary midterm election. Republican candidates are embracing the playbook of the former president and trying to seed doubt about the integrity of the process. Republican lawmakers are curtailing access to the ballot. The threat of political violence feels baked in with only a few days until Election Day. As with the lead-up to November 2020, experts are making dire predictions about what could happen—but in many ways, the risks are even greater this year.

In the months after the 2020 election, many Donald Trump supporters believed that he could overturn his loss by proving the election was stolen, by orchestrating an alternative slate of Electoral College electors, or by winning some hail-mary victory at the Supreme Court. Even after the vote was certified by Congress, conspiracy theorists still argued that Biden would be arrested on Inauguration Day, martial law or the Insurrection Act would be invoked, and power would be transferred to the military. That those fantasies have been (repeatedly) disproven but not rooted out has only raised the stakes for what could happen this year.

Next Tuesday, 28 states will determine who’s in charge of running elections in 2024. Of those, more than a dozen feature election-denying, Trump-aligned candidates.

Should they win, the consequences for democracy are dim. They’ve pledged to enact seismic changes to how elections are administered, including eliminating “mail-in ballots,” drop boxes, and early voting, repealing automatic voter registration, and decertifying voting machines. Combined, these “America First” candidates have raised at least $6.2 million, according to OpenSecrets, and they’re currently in close races in Arizona, Michigan, Minnesota, and Nevada For many of their supporters, these contests are essential to lay the groundwork for Trump to reclaim the presidency in two years.

Should those candidates lose, the consequences are equally dire, but for different reasons. A widespread perception of fraud—whether or not that perception has a legitimate basis in fact—will likely result in “heightened threats of violence against a broad range of targets―such as ideological opponents and election workers,” said a recent joint report from the Department of Homeland Security, FBI, U.S. Capitol Police and National Counterterrorism Center.

So what might those threats look like, and how could the midterms be disrupted, delayed, or delegitimized?

Outright Violence

Two in five voters say they’re worried about threats of violence or voter intimidation at the polls this year, and the environment may become even more incendiary between now and Election Day.

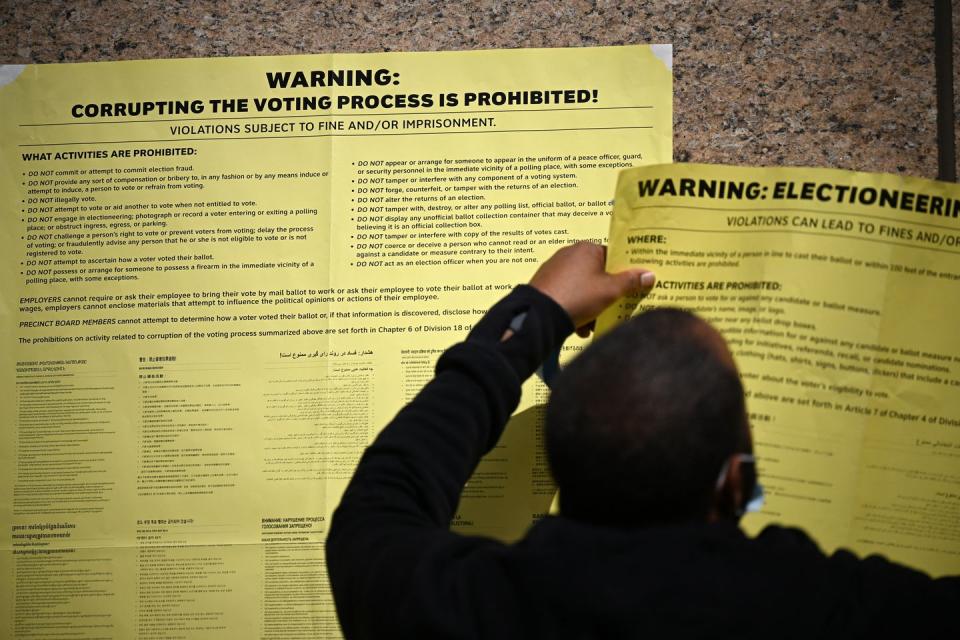

In Arizona, groups of armed activists in military-style gear had stationed themselves near drop boxes, and at least two lawsuits argued that their presence constituted voter intimidation. One federal judge refused to ban the group from congregating, but another has now prohibited them from taking photos or videos of voters, openly carrying firearms near ballot boxes, or posting information about voters online.

If such paramilitary groups show up to poll sites on Election Day, there’s relatively little to stop them. Only six states affirmatively mandate that law enforcement be stationed at polling places or be on notice to appear if requested. Last week, New Jersey joined that list after the legislature unanimously passed a law that allows plain-clothes police officers in poll sites. But merely having officers present may only deter the most obvious threats, while doing little to prevent less clear-cut forms of voter intimidation or suppression.

“Your average law enforcement officers, as good as they are, are not dealing with elections on a daily basis,” says Neal Kelley, the former registrar of voters for Orange County and the current chair of the Committee for Safe and Secure Elections, a cross-partisan collaboration between election administrators and law enforcement to protect election workers.

Kelley and the committee are working to train police officers and prepare election officials for different scenarios, including active shooters.

“If you're calling 911 on Election Day, I think it's too late,” he says.

Disruptions to the Process

Election deniers don’t have to resort to exotic or blatant acts of violence and intimidation, however. They have already found ways to throw sand in the gears of more routine parts of election administration.

In New Hampshire, a group of “freedom fighters” has been encouraging voters to write in the name of a candidate who’s already on the ballot, which has forced poll workers to count those ballots by hand. The end result is a process that’s both slower and less accurate.

“These fringe actors are trying to break down our democracy by needlessly burdening our local election officials and volunteers,” says Liz Wester, director of the New Hampshire Voter Empowerment Task Force.

The Republican National Committee and its allies have launched a nationwide campaign to recruit poll watchers, who can observe voting and, in some states, lodge complaints about improper behavior. Former Trump attorney John Eastman recently urged prospective poll watchers in New Mexico to file complaints that could form the basis for court challenges, and jurisdictions have been preparing for volunteers who may be highly suspicious, misinformed, and unruly.

Milwaukee is training poll workers in what to do if poll watchers refuse to follow the rules or if they challenge a voter’s eligibility because of their race or the language they speak, which isn’t permitted. In North Carolina, the members of the State Board of Elections unanimously voted to tighten restrictions on poll workers after a series of confrontations, but they were overruled by a commission appointed by the Republican-controlled legislature.

And then there’s the threat of election deniers becoming poll workers themselves, like the two ex-Proud Boys reportedly doing so in Miami-Dade County. Back in 2016, while Kelley was still the registrar of voters in Orange County, he submitted the names of his poll workers to the Department of Homeland Security for vetting, and he now recommends that other officials do the same. “Especially in an urban county, where you're hiring thousands of people, they might have some sort of agenda,” he says.

In Michigan, the clerk in Macomb County reportedly hired a social media influencer to help recruit poll workers. Before taking the position, the woman had participated in a rally at the Michigan Capitol alongside armed members of the Proud Boys, had live-streamed a “Stop the Steal” protest at the home of the secretary of state, and attended the Jan. 6 riot at the U.S. Capitol, where she told the crowd to “storm the gates.”

Endless Litigation

Bad-faith actors could also make voting and the vote-counting process as slow and miserable as possible.

After the 2020 election, lawyers aligned with Donald Trump filed between 60 and 70 lawsuits, and post-election litigation rates will likely continue to rise, says Rick Hasen, an election law professor at the University of California Los Angeles School of Law and the writer of the Election Law Blog.

Part of the problem is that election laws often are ambiguous, which leaves opportunities for candidates to sue after a loss.

In Wisconsin after the 2020 election, Trump-affiliated lawyers claimed that election officials didn’t have the authority to authorize drop boxes, and the state’s supreme court agreed. Though his lawyers never alleged the boxes were used to commit election fraud, Trump seized on the court’s decision “to argue that the decision proved the election was illegal and that he actually ‘won,’” Hasen wrote in a recent brief. Distortions of such technicalities not only provide political capital, but they can also be used to fundraise.

Other laws provide openings to significantly disrupt the vote-counting. In 22 states, automatic recounts are triggered when the margin of victory is below a certain threshold, including in battleground states like Arizona (0.5%), Florida (0.5%), Pennsylvania (0.5%), New Mexico (0.25%), and Michigan (2,000 votes are less).

In 41 states, a recount can be requested by a losing candidate, a voter, a group of voters, or other “concerned parties” (such as a political party or election officials), and Republican candidates have already abused these laws to demand frivolous recounts. In Colorado, for example, conspiracy theorist and former election official Tina Peters contested her primary after losing by 14 points.

All of this means that the threats—of violence, unrest, and bureaucratic meltdown—won’t end on Election Day. Because it requires time to receive, verify, and count all of the ballots, and then to double-check that the results are correct and provide for potential recounts, some states won’t certify their results until the second week of December. “That’s when I’ll breathe a sigh of relief,” said Kelley, “Which will be very short-lived, going into ‘24.”

You Might Also Like