'Testing Is Really Vaccination for the Economy': We Need Millions and Millions of Rapid Tests

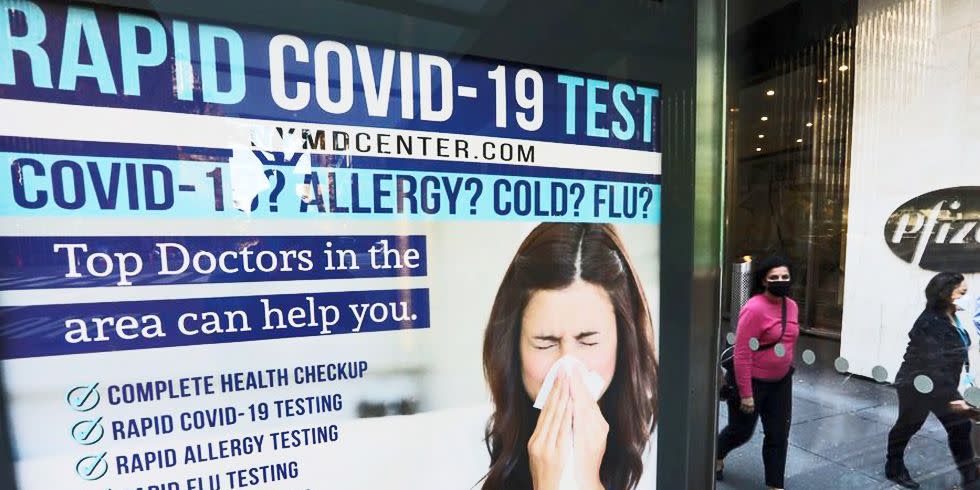

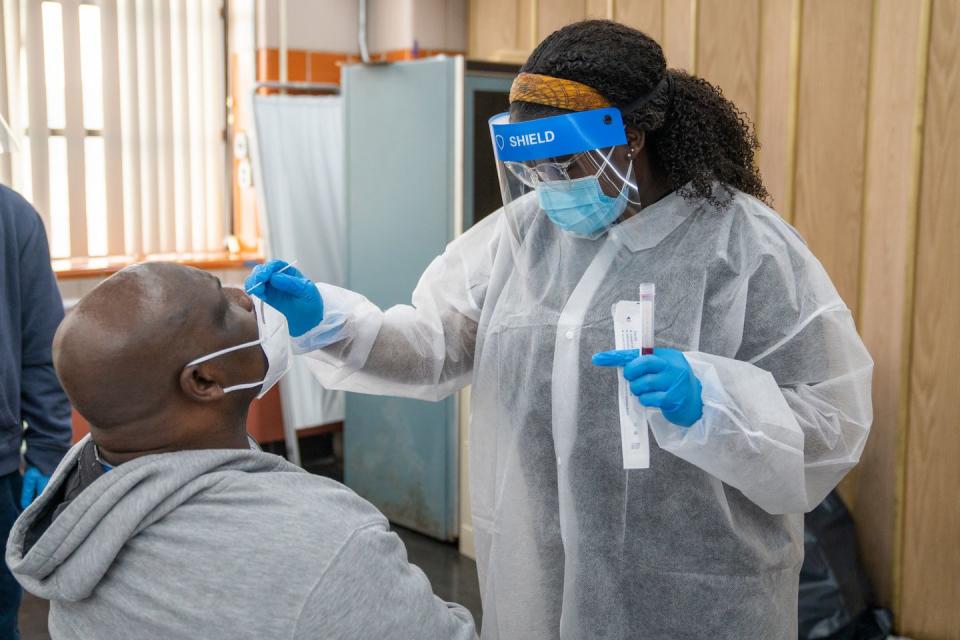

When I went for a COVID-19 test at a Manhattan urgent care clinic on Wednesday, the whole thing ended up being a two-hour commitment. I went right when it opened and the line was already down the block. Once inside, there was the usual song-and-dance of giving your insurance information ahead of a purportedly free test, then sitting in the waiting room until it was time to go into one of the examination rooms to wait for a nurse or physician's assistant to take your vitals and all that. Then, finally, the rapid-test swab went in for about 12 seconds and it was all done and dusted. I learned I was negative (as expected; it was an abundance-of-caution thing) via email within half an hour. In the end, getting the results was the most efficient part of the process.

I found myself wondering why there are not tents set up all over cities and towns across the richest country in the history of the world where you can just give your information, get tested for free, and leave promptly. I wondered how often we would all get tested if this were the case. In May, we looked at the promise of what's called "surveillance testing," where people are tested regularly—say, once or twice a week—regardless of whether they have symptoms of COVID-19. The aim was to catch cases early and prevent the spread. The idea was to start with frontline workers, then expand it to include essential workers in grocery stores and other jobs that involve a lot of face-to-face contacts with the general public every day, then move out into the general population.

That would've required ramping up our testing capacity in a big way, so of course it went nowhere at a time when the President of the United States was yelling that testing "creates" cases, by which he really meant bad headlines for him. A pandemic is a bad time to have as your leader someone who is incapable of putting the needs of others above his own, and in fact struggles to think strategically about the future in any way. The result is that many states have barely developed test-and-trace infrastructure, much less this level of consistent testing, and now we're in the middle of a third wave.

But the United States is also on the verge of a new presidency—and, hopefully, an approach to the novel coronavirus pandemic that maintains even a modest grip on reality. It seemed like a decent enough time to circle back with one of the people I spoke with for that May article on surveillance testing: Bob Kocher, who at the time was leading the state of California's testing strategy as part of Governor Gavin Newsom's coronavirus task force. Kocher is back in private practice now, but he's still got a lot of thoughts on all this—including on how "testing is vaccination for the economy."

Our conversation has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

What do you see as the testing solution? Can't we just have some outdoor tent where you give your information, you take a rapid test, and then you leave?

You've just described it, and the question is, why aren't we doing it yet? In Asia, there are—varying from free to $5—self-done, rapid, 10-minute, lateral-flow antigen tests that are in baskets by the doorway of schools, churches, business, office buildings. You take them, you spit on them, you wait 10 minutes, you show people the thing and then you go inside. And these tests are somewhere between 80 and 90 percent accurate, and if you do them multiple times, they end up being very accurate. Because the odds of it being falsely wrong multiple times is low. That's how you get on with your life.

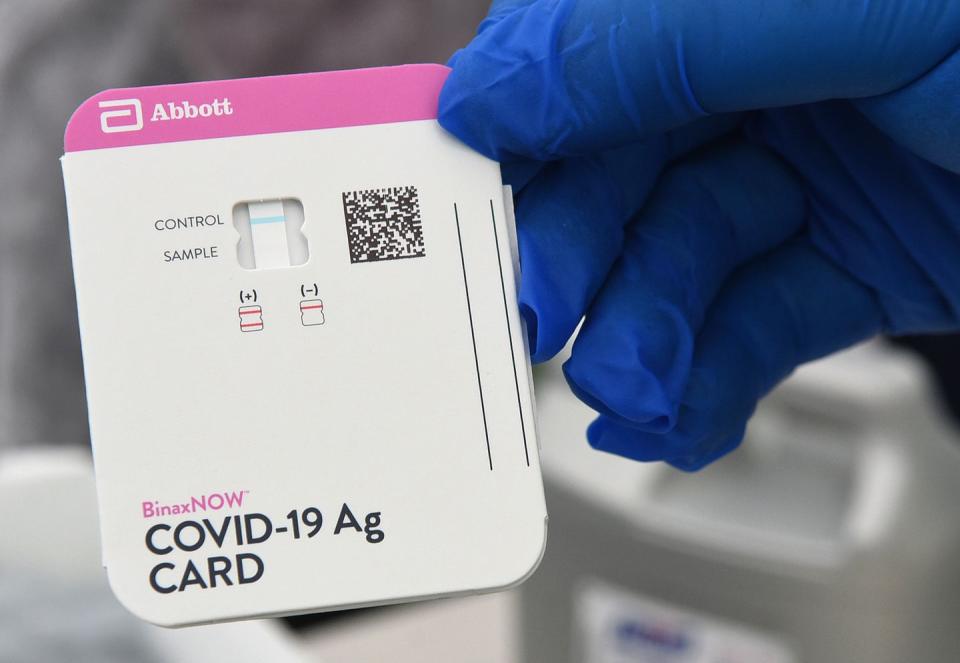

We in America have, relatively speaking, very few of these tests, and so they're not available. So instead you go wait in a clinic and they either run the rapid test—which is expensive. It's a $30 to $40 little plastic cartridge that runs on a $5,000 machine that needs to be done by a healthcare professional, that can only spit out about 12 an hour. It's just super slow, or you go and have them take a sample and run it through a machine the size of a minivan in a central lab and run a PCR test on it and that takes several hours. And so, we need to get to these self administered basket of antigen tests that we do before we go to different activities, or once a day and you have an app on your phone that proves it was negative. That's what we need to do.

I was going to ask how often we should be getting tested.

Optimal would be once a day—not multiple times a day, to be clear. Ideally, people are tested every day or at least two times a week, and that would allow you to very rapidly identify positive cases and then you combine that with a very effective program of public incentives and penalties to make people who are positive isolate themselves, and then you get transmission to nearly nothing and we could have a lot of normal activity.

Are there any examples of robust surveillance testing in this country?

The NBA. Sports leagues have been by far the most ambitious here, but there are some successes at universities. They're kind of elite institutions, but Harvard's done a really good job screening everybody. Dartmouth has. So some of the universities that are in person are demonstrating that you can do rapid, population-level screening identification and not have terrible outbreaks.

So there are these bubbles where they're doing the kind of program that we should want to have on a state level or nationally?

Absolutely. And like, it's just a matter of making the bubble bigger, right? Like there's nothing magical about a bubble of 3,000 people versus 3 million, you just have to do a lot more tests, right? China's made bubbles in Beijing, right? So you can do it, but the critical thing is you have to test people often enough that you find the positive cases and then pull them out of the bubble and isolate them until they're clear. The CDC here does not encourage you to retest people before you let people back in the bubble. The current US guidance, which I think isn't right—or isn't what I would recommend—says that after 10 days of isolation and 24 hours at least of no symptoms, you're allowed to go back after being positive into the community.

They've done this in East Asia. What's our excuse? Is it financial, is it logistical, is it just a lack of will?

A handful of things. The people who are making the tests in China and Korea haven't come to the US to market and sell these tests. That may be because the markets in those countries are so enormous that they don't have any more tests to sell. In the US, the current suppliers of antigen tests—the two biggest are a company called Quidel in San Diego and then Abbott Laboratories, and both of them are making as many antigen tests as they can, but the demand for those tests is at least 10 times the supply, and so there's not enough tests to do what we're [talking about]. If the US wanted to have baskets of tests available at all schools and business and nursing homes like I described, we need a lot more production of the tests.

A very important policy question for the Biden-Harris transition team is gonna be, do they want to have the US government either create incentives or even invoke the Defense Production Act to get more of these tests produced domestically so we can use them in America. Because the whole world is trying to get these tests, and so we're one large market but we're actually the minority of the global demand here. So unless there's more production, we're gonna have a hard time meeting our needs in the near term. These companies are investing in more manufacturing capacity, but when you build a factory to make these tests, it takes at least six months, because you need to put in the manufacturing equipment and learn how to do it and then the FDA has to come in and inspect your factory and sign off on your processes.

So you need to be making those investments—I would argue yesterday—or now if you want to have this sort of ubiquity of tests later. Even with a vaccine, we're gonna need much more in the way of rapid testing than we have today, because not everyone's gonna get vaccinated for at least a year. The vaccine's probably not gonna be a permanent solution to making you immune. You probably will have to get a booster shot, and so COVID is going to be in our community.

What is the fail rate on these rapid tests? Because I know there's more risk of a false negative than with the PCR test, right?

The PCR tests are, let's say, near-perfect, but the results take longer to come back. The thing that makes them more accurate is actually the sample collection. The PCR gets it sort of perfect. The rapid is a much less sensitive test, but it will detect somewhere between 80 and 95 percent of the cases. I would argue that they're absolutely good enough, and if you do them more than once, mathematically, the odds of them being wrong two or three times in a row—it makes them as good as a PCR test.

With the kind of uncontrolled community spread we're seeing, is there any way for us to test our way out of this?

It's difficult to imagine how we can test our way out of it, because when a test is positive, unless you can isolate that person and then the people that exposed and get them tested and isolated too, you just keep transmitting the disease. Testing is how you know who needs to be isolated, but most of the country doesn't have an effective way today to follow up to make sure that people who are positive actually are pulled out of the community and not exposing other people. In most of the country, the job for this is called contact tracing. Most of the country has really poorly developed contact tracing capabilities, and it's talking to the minority of the people who are positive, and so without some follow through to help ensure that people are able to stay safely isolated and provided for with food and medical care, I don't think testing alone sort of fixes this.

Because even if you try to be a good citizen and isolate yourself, you could need some support or you might need a place to actually stay. In California, we still have hotel rooms that we can offer to people who need them, but we're having a lot of problems in California, people spreading it in crowded apartment complexes or multi-family homes—they can't isolate. And so, I don't think testing alone works, because you have to have testing plus a way to safely isolate and care for people that are infected and watch to make sure that they don't deteriorate.

Right now, the number of cases—130,000 cases yesterday, that's kind of an impossible number to contact trace. So I think we need to do something to lower baseline transmission and then testing can be a lot of that solution to help us sort of maintain a better level of performance.

So what does the testing system look like in your ideal world?

I think self-administered rapid tests are the best way to go, because they're the cheapest and they're rapid, and you can do it without having to have a whole bunch of labor to handle samples and move them back and forth. If you're doing it in a community that's very stable, you certainly can do the self administered PCR test, where you break open a box, spit into a tube and drop it into the mail. And the prices for the PCR testing are falling quite a bit—the Broad Institute, a big testing lab in Boston, is able to do PCR testing for between $10 and $20 now.

But let's pretend the NBA wants to bring people back to basketball games. You won't want to have everyone who's going to that game have to go get tested the day before and wait for results. You want to have them come to the arena a few minutes early and do an antigen test and show when they come to the door that they're negative. That would be much more practical. It's logistically easier.

For schools, universities, offices and factories, you could do the self-administered, mail-it-to-a-central-lab PCR test. If you have people going to the same place every day, that's perfectly OK. But for schools, I think antigen tests are even easier, because they're immediate and they're cheaper. There are a lot of public school kids, and you can do antigen tests two, three times a week, and you end up with the same level of test accuracy as you would for the PCR test. And they're very simple.

For cities, there might be people who don't go to school, don't work at a workplace that does testing. For that population you would want to have the tents, and tell all citizens, "Once a week we want you to go to the tents and have a test done." And again the easiest thing to do would be the antigen test, because they're fast and immediate, there's no sending anything out, and you could get a QR code at the end saying, you know, "here's your pass to be in the community and it expires in a week."

How long would it take to get up to this level of rapid testing?

It's a six-month process to get to dramatically more of them. There's some things they could do to help the US get even more of them from these companies. The government could tell distributors that they will guarantee that all antigen tests they buy will be sold, and so you could take the risk away by providing a backstop. The government could raise the price it's willing to reimburse for these tests to make them more profitable, and that might lead to shifts globally of more tests coming to the US from other countries. It's possible that there are some supply constraints in the plastic parts that are used in these tests, where the government could help get more raw materials, which would make it easier to make more of the tests. The FDA could rapidly approve new assembly lines.

There are things we could do to speed this up a little bit, but it's sort of a six-month-ish timeline, cause if you're gonna invoke the Defense Production Act, you have to get other factories that are making other medical products to convert over to make these things and teach them how to do it and so that's gonna take, that's like six months is sort of the minimum amount of time.

Could we try to buy more from, say, South Korea in the meantime?

We could try to buy lab tests from South Korea. We aren't doing that today, so we could call up the South Korean test-makers and be like, "We think your test is awesome, can you sell it to us? We will help you get it FDA approved and we'll pre-buy a bunch of them so you're not taking risks." We could try that. I don't think that there's actually any extras to buy, so I don't think that's probably gonna work.

I think we more have to go to these American companies and say, "You're sending 70 percent of the tests to other countries, can we please buy more of them?" And they'll be like, "We aren't sure if we want to," and then we'll say, "Well, can we pay you more for them?" And then on the margin, they will send us more.

So basically, they should've started this when we spoke in May.

Yeah, given what we all know, the decision in May to scale up testing manufacturing would be paying a lot of benefit now. I mean, testing's really the vaccination for the economy. Like a vaccination is wonderful, and the data's promising, but we won't be able to vaccinate more than half of our population for at least a year, and so in the meantime if we want to get back together and do schools and business, you need testing, and to do that you need a lot of tests, and we don't have enough.

The other nuance here is who's gonna pay for the testing. So right now, insurance companies are paying for these tests—well, the PCR tests. For the antigen test, it's a patchwork for whether or not the insurance company will pay for it or you have to pay for it out of pocket. In America, all the tests in theory could be very cheap, they may not be. It depends on who you're buying the tests from. There's a question about who's gonna pay and what the prices are gonna be that needs to get worked out, and there's a bunch of things the government can do to either like control what the prices will be or not. If we want people to grab a test and do it once a week, we need to have a way to have it covered by your insurance, and then have the price be fair so we're not just jacking up everyone's healthcare costs.

I mean, if we're asking people to do this all the time, it's gotta be free, right?

Yeah, I think so. But let's pretend that you're running a factory, and you're paying your workers minimum wage. If you're buying baskets of antigen tests from somebody, it's expensive, and so you might take it out of the wages of the workers. Or like, today the government is not providing to anybody the free tests, and if Congress passes the stimulus bill, that will be one of the things that I think would be wise to put into the bill—a bunch of federal funding so you can make sure that people are not gonna have to pay out of pocket for these tests, and that the prices paid ultimately are fair.

You Might Also Like