How to Talk to Your Friends About QAnon

In March 2020, Leila Hay suddenly found herself with a lot of time on her hands. The 19-year-old from the United Kingdom had finished her university semester and was—like millions around the world—in lockdown as the coronavirus swept the country. Feeling isolated, she says she turned to social media for commiseration and distraction. But instead of real human connection, she landed on the conspiracy theory known as QAnon.

“I saw it everywhere,” Hay says of the now infamous conspiracy group. “I started doing my own research, and I ended up falling down the rabbit hole. It happened really quickly.”

QAnon is hard to define, but journalists like Brandy Zadrozny—a reporter at NBC News who has been following it since its start—have tried to make sense of its rise. In 2019, Zadrozny wrote: “QAnon is a convoluted conspiracy theory with no apparent foundation in reality. The heart of it asserts that…the anonymous ‘Q’ has taken to the fringe internet message boards of 4chan and 8chan to leak intelligence about Trump’s top-secret war with a cabal of criminals run by politicians like Hillary Clinton and the Hollywood elite. There is no evidence for these claims.”

Hay saw similar (baseless) stories on Facebook, where QAnon theories once spread like wildfire. She read posts about child sex trafficking rings that American politicians supposedly controlled, posts outlining global financial conspiracies, and even claims that the elite were kidnapping and drinking the blood of children. Once she started reading, she couldn't look away.

“From the moment I woke up to the moment I went to bed, I was consuming QAnon content,” she says.

Hay managed to shake off her sudden fascination with—and openness to—QAnon's wild web of lies, but thousands more around the globe still consider themselves “digital soldiers” for the cause. And in the lead-up to the contentious election in the United States and as coronavirus threatens countries around the world, the group's influence continues to grow.

What began as a fringe movement has exploded into the relative mainstream. One recent Civiqs poll reported that just 6% of registered U.S. voters believe in and support QAnon, but that number doesn't capture the full picture. According to the Pew Research Center, in the United States, awareness of QAnon has doubled since March. Around 41% of Republicans polled had heard of QAnon. Of them, 40% said the group is a “good thing” for the country, while 32% said it was “somewhat good,” and 9% said it was “very good.” In contrast, 77% of Democrats who had heard of QAnon responded it is a “very bad” thing.

But attitudes toward QAnon aren't a strictly partisan issue. As the Pew report notes, young adults may be especially vulnerable to falling into its trap. Researchers found that adults under 30 are the most likely to say QAnon is a good thing, while 29% of those ages 18 to 29 say the same, compared with 20% or less of any other age group. Despite the (belated) steps that some platforms like Facebook have taken to curb QAnon content, the group's ideologies and dangerous lies are spreading. So even if you don't know someone now who's espousing these beliefs, you might soon.

It can be hard to know just how to react or what to say to a loved one who is sharing or promoting QAnon. It can feel easiest to say nothing or just walk away. But if you're hoping to help someone get out of QAnon or are at least trying to preserve your relationship with them, there are steps you can take.

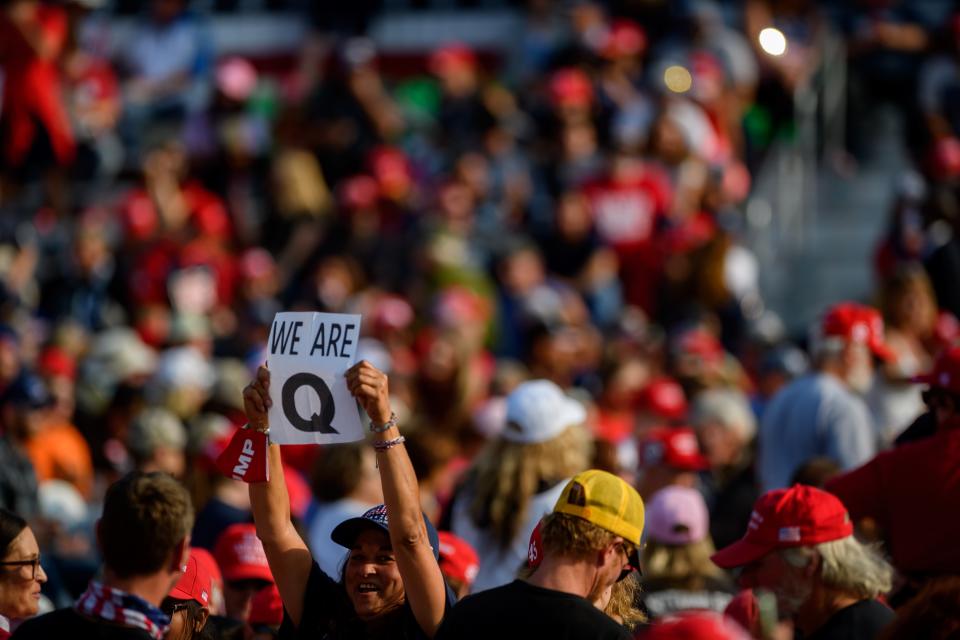

President Trump Holds Campaign Rally In Pennsylvania

Understand how we got here.

Though it's hard to pinpoint the group's exact start, many remember the “Pizzagate” scandal as a pivotal moment. In the lead-up to the 2016 election, a theory was posted on the website 4Chan that a pizza shop owned by a Hillary Clinton supporter was actually the headquarters of a child trafficking ring led by Clinton.

Since then, this entirely imaginary cabal has grown to include nearly every celebrity on earth, from Tom Hanks to Chrissy Teigen. Who can stop this sex trafficking nightmare? According to QAnon, the true savior is President Donald Trump.

Though thoroughly debunked, Q’s message spread across social media websites, appealing to and tapping into other groups that spread similarly false and dangerous conspiracy theories, from anti-vaxxers to those who peddle in anti-Semitic ideologies.

President Trump Holds Rally With Senator Ted Cruz

“What I think unites all of these folks is they are searching for something,” Zadrozny tells Glamour. “They are trying to find an answer for an unanswerable question. So ‘covfefe’ [Trump's 2017 tweeting mishap] isn't a typo; it's a secret message to you, and it fulfills your belief, your political belief, your hope that you are backing the right candidate, and the right party, and the right movement.”

It was the appeal of decoding secret information that Hay says helped her slip so quickly and deeply into becoming a believer.

“I remember seeing a post that was decoding Hillary Clinton's emails from 2016, and it kept mentioning things like ‘pizza,’” she says. “At the time it just made sense because I couldn't understand what she meant. So when people were telling me like, Oh, it’s code for children, I just assumed that’s what it was.”

The spreading of misinformation so obscure may seem innocuous, but the ramifications are real. As the Guardian reported, at least one kidnapping plot and two actual kidnappings, along with at least one murder, can be traced back to the group. In 2019 the danger grew so great that the FBI has referred to QAnon as a “domestic terror threat.” In recent months, major social media platforms have taken steps to start banning QAnon content to help stem the tide of misinformation.

Still, it's become increasingly tricky for people not steeped in QAnon culture to recognize when a seemingly harmless hashtag or phrase is a nod to the group. For example, QAnon has taken to using the slogan and hashtag #SaveTheChildren in an attempt to spread misinformation about child trafficking. The same hashtag has been used in the past—by the very real global humanitarian organization Save the Children, which is legitimately attempting to help needy children around the world.

The use of the hashtag in connection with QAnon has likely led some to partake in a conspiracy theory and its falsehoods without even realizing it. Organizations dedicated to actually ending human trafficking are now saying QAnon supporters are doing far more harm than good and that they “distract and distort” reality.

US-POLITICS-CONSPIRACY-QANON-PROTEST

Be empathetic.

So what do you when someone in your life starts sharing memes or posts that veer into conspiratorial territory? Or when a friend is captioning her Instagrams with disturbing hashtags? For starters, experts don't recommend reacting in the heat of the moment.

“It’s very important to remember that QAnon is filling a need,” says Doni Whitsett, a clinical professor of social work at the University of Southern California (where I'm also an adjunct professor). “People are feeling lost and very uncertain, and human beings don't like to feel uncertain.”

Like Zadrozny, Whitsett says for many, the group seems to have all the answers that they're looking for. “Even though these are false, they're answers. When people are feeling anxious that binds their anxiety. They can tie it up in a little compartment and say, ‘This is why things are happening, this is why I feel so lost and confused,’ and it takes away a lot of that confusion.”

It takes a concerted effort and a lot of empathy and support for a person to find their way back from that. For Hay, it was the realization one day that Q had swallowed her entire life and left her dangerously close to being alone forever.

“I realized it was really badly affecting my life,” she says. “It was ruining everything for me.”

She began reading more mainstream, reputable news outlets, and reports that contradicted what she'd been led to believe. She went out with friends more and began to engage with the world around her rather than the communities conjured up by QAnon. Again, she was lucky. According to Zadrozny, there are still thousands of Facebook pages, YouTube accounts, and corners of the internet dedicated to spreading misinformation.

Engage their curiosity.

It may seem counterintuitive to encourage someone immersed in QAnon to talk more about their theories, but as Whitsett says, those interested in QAnon are likely naturally curious people. Having a conversation with them about it gives you an opportunity to open them up to different sources.

“If they're curious, I encourage the curiosity, but I want them to look at certain internet sites that show the casualties that have happened to people who have gone down the rabbit hole,” Whitsett says, specifically pointing to websites like Reddit’s r/QAnonCasualties, where ex-believers come and share their experiences after leaving the belief system. “If they're curious and they're open, that would be good for them to also look at, and then they can make their own decisions.”

If you can handle it, Mick West, a conspiracy theory researcher and author of Escaping the Rabbit Hole, told Engadget, it may be a good idea to listen to what a QAnon believer has to say, and introduce them to new sources along the way. This will again encourage their own curiosity, and perhaps help persuade them to believe fact over fiction.

“You can't just simply dismiss their ideas,” West said. “You’ve got to be able to, at the very least, show that you understand what the person is talking about, which means that you do actually have to listen to them for a while, and try to figure out why they believe what they believe, and then talk about why.”

Don’t try to fact-check.

Whitsett, Hay, and Zadrozny all noted the dangers of attempting to fact-check friends and family because this could isolate them further if they think you too are out to get them. And, perhaps most important, they think what they are doing is right, and your stopping them is wrong. Zadrozny says to think of it this way: “If you believed that there was a cabal of people in the highest ranks of government hurting children, if you truly believed this, wouldn't you do anything to make people understand that harm?”

Whitney Phillips, a communications scholar at Syracuse University who studies misinformation, rhetoric, and information systems, also suggested to the New York Times that those attempting to fact-check could instead ask where the person received the information, and help increase their internet literacy along the way.

“I’d nondefensively ask them, ‘Do you know how Google works?’ ‘What do you think my news feed looks like? Do you know why yours looks that way?’” she says. “So many people think this technology is magic or the natural state of how information moves. But it’s not. It’s designed this way. And if people better understood the mechanisms and the economics, maybe then you can talk about the content.”

St. Paul, Minnesota, Save our children protest, Protesters holding signs.

Get the person outside.

Hay and other previous believers we spoke to for this piece say one of the biggest factors for their belief in Q was their isolation. So, whenever possible, try to get your friend or family member as far away from a screen and back into their regular life.

“It’s important to know what need is being fulfilled,” Whitsett says. “For example, if the person is feeling alienated from society and from their family and their friends, then we need to reconnect them.”

Joan Donovan, the research director at Harvard’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy, shared this sentiment with the Washington Post, noting it may be a good practice to show a QAnon believer what they are missing.

“[Show them] how much of their life they’re missing out on and how much it’s impacting your relationship,” Donovan told the paper. “And if they can’t have a conversation about someone else, a conversation that’s mutually beneficial and interesting, then there’s a different kind of problem going on.”

Try not to abandon them.

Being around a QAnon believer can feel daunting, especially if you have opposing ideological beliefs. But if you can handle it, try to stick around, even if it hurts. Because once the person is out, they will need you more than ever.

Steve Hassan, a cult deprogrammer and mind control expert, says one way to try to stay in the person's life is to build an even deeper bond that starts by making a deal.

“Don’t think you can talk them out of it,” Hassan told Forbes. “Get into a strategic and interactive mode by building a good rapport with them, asking good questions, and giving them time to answer before following up. Tell them, ‘Share with me what you think is a really reputable article. I’ll read it and get back to you on it, if you agree to read something I share with you. But the deal is we both listen respectfully to each other.’”

As for Hay, she says these chats with her inner circle may be what saved her.

“I've had a lot of discussions with my family and friends, try and figure out how I can get better on this,” she says. “It is getting better. There is still a lot of work to do, but I’m getting there.”

Originally Appeared on Glamour