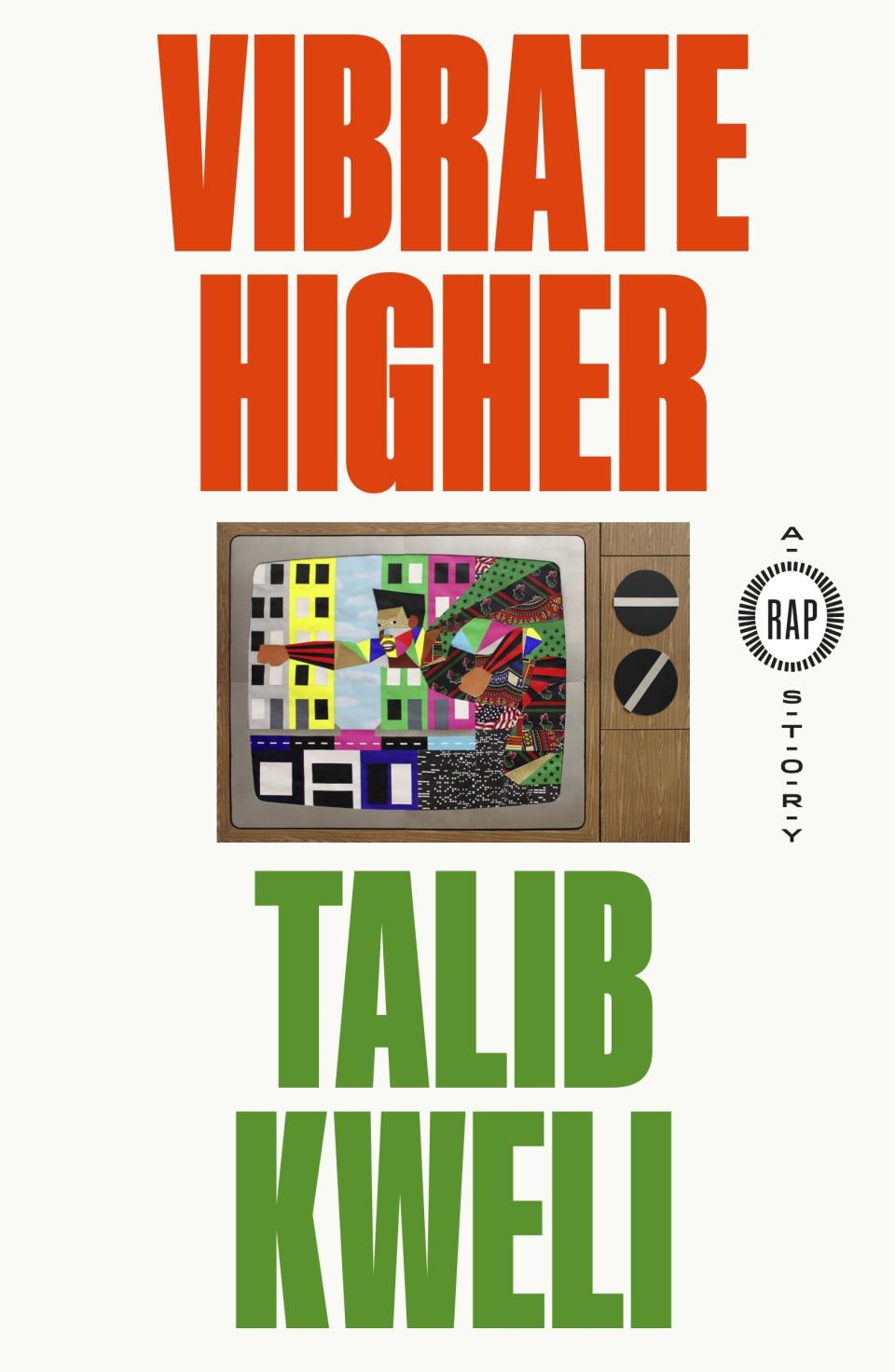

Talib Kweli Reflects on his Relationship with Kanye West in New Memoir Vibrate Higher

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

I’m not the hero. I’m the guy in the crowd making fun of the hero’s shirt. —Seth Macfarlane

Black Star was my introduction to the world. Reflection Eternal was proof that I could hold my own as an MC. My debut solo album would have to prove that I wasn’t a fluke, that I was an exceptional MC and here to stay. Would I be able to turn in a classic piece of work without a producer as talented as Hi-Tek overseeing it? Quality gave me the opportunity to fully realize the music in my head without any roadblocks. However, sometimes roadblocks keep you from danger. DJ Scratch, who produced “Shock Body,” was the first producer to land a placement on Quality. I took a Megahertz track down to Jamaica to find the reggae superstar Super Cat and throw him on a song called “Gun Music”; I ended up finding his young brother Junior Cat, who is on the song with Brooklyn’s own Cocoa Brovaz. I enlisted Bilal to help me record a version of my favorite ballad, Eddie Kendricks’s “Can I,” which I called “Talk to You (Lil’ Darlin’),” and I flew to Los Angeles to record “Put It in the Air” with DJ Quik. On “Stand to the Side,” one of the two Quality songs produced by the late, great J Dilla, we brought a piece of wood into the studio for Savion Glover to tap on. I didn’t care that you couldn’t see him when you listened; I was trying to incorporate all types of Black music into one hip-hop opus.

Quality starts with Dave Chappelle doing a civil rights character he made up on the spot over a beat produced by the Fyre Dept, which puts the listener in the same space they were in when they heard Dave doing his Nelson Mandela impersonation on the intro of the Reflection Eternal album. Lyrically, I knew I had to top what I had already done with Black Star and Train of Thought, but I was also coming into my own as a songwriter and I was starting to have more fun with my craft. I was taking the lessons I’d learned from working with Yasiin and Hi-Tek and was finally creating my own uninhibited musical vision. On the Megahertzproduced “Rush,” I talked a lot of shit over rock guitars, and on “Joy,” featuring Mos Def, I may have created hip-hop’s first dedication to doulas while detailing the birth of Amani and Diani. On “Won’t You Stay,” produced by Supa Dave West and featuring my good friend Kendra Ross, I stepped up my hip-hop ballad game by trying to put myself in the shoes of the women who are in love with musicians, for better or for worse.

The most interesting development of the Quality recording sessions was my burgeoning relationship with a young producer named Kanye West. One night late into the recording of the album, Kanye walked thru the studio door looking for Yasiin Bey. Yasiin had said he was showing up to record vocals for “Joy” that night, but he had yet to arrive. I invited Kanye, who I had never met, to wait for him. When Kanye mentioned that he produced, I asked him to play some tracks. When he pushed play on that CD, my jaw dropped. Not since Hi-Tek had an unknown producer played something for me that literally gave me chills. This was some of the best hip-hop I had ever heard, yet no one knew about it. Two of the tracks Kanye played for me that night made it onto Quality, “Good to You” and “Guerrilla Monsoon Rap,” featuring Kanye, Black Thought, and Pharoahe Monch.

Kanye’s star began to rise after that initial recording session. In September 2001, Jay-Z dropped his career-defining masterpiece album, The Blueprint, with the lead single, “Izzo (H.O.V.A.),” and many of the album cuts produced by Kanye. Kanye can be seen in the video for “Izzo,” mean-mugging and showing off his tats. As fans of the art began to dissect The Blueprint, they began to understand that Kanye and Just Blaze were the producers responsible for Jay-Z’s new but instantly classic sound. However, the more people began to check for Kanye West beats, the more he tried to explain that he was a rapper who only started to produce so that he could get his raps out there. The Blueprint secured Roc-A-Fella Records a dominant spot in the hip-hop food chain of the early 2000s, and as one of the main architects of its sound, Kanye became the go-to guy for not just Roc-A-Fella artists but any hiphop or R&B act looking for a hit that dripped with authenticity. Often showing up at events dressed like a walking contradiction of styles with his blinged-out Roc-A-Fella chain, Polo sweaters, and Louis Vuitton book bag, Kanye relished every opportunity to spit in the face of those who said hip-hop artists had to fit in neat little packages. By keeping his rhymes unflinchingly honest and staying on top of his production chops, he was the first artist to be embraced by the underground and mainstream fans in equal measure.

Golly, more of that bullshit ice rap I gotta apologize to Mos and Kweli

— Kanye West, “breathe in breathe out”

Kanye gave me a beat CD the week after I turned Quality in to Rawkus for shipping. One of the tracks on the CD was based around snippets from a live recording of Nina Simone’s classic song “Sinnerman.” Kanye took Nina’s haunting vocals and made an intro with them, then he chopped her piano playing to hip-hop perfection. The moment I heard it, I made it my mission to get this track. This was only a year after we first met, but within that year Kanye had gone from the guy who would offer me any of his tracks to the guy doing songs with Mariah Carey, to whom, he told me, he’d promised that beat. I asked him to keep me in mind if she changed hers, and I called him once a week to ask him about it in case he forgot. After about a month of my harassing him, he finally agreed to give me the beat.

When I first wrote to the track that would become “Get By,” it was in four-bar intervals that ended with the refrain “just to get by.” I wrote a bunch of those and kept the ones I liked, and that’s what became the heart of those verses. After I laid them, I invited Kanye to the studio to listen. His idea was that this song should be hip-hop gospel, and he began to improvise the chorus, singing in a high-pitched wail that was meant to give me an idea of what the person singing the hook should sound like.

The melodies of the “Get By” hook that Kanye came up with are infectious, but the hook is the lyrics:

Just to stop smoking, and stop drinking

but I been thinking, I got my reasons

just to get by

Everybody has vices; I find it hard to trust people who say they don’t. Anyone who has been thru any struggle can identify with the hook of “Get By.” To bring out the gospel that Kanye was looking for, he wanted to use the Harlem Boys Choir. He didn’t even have a deal yet and he was already thinking big. The Harlem Boys Choir was too expensive for me, and Kanye used them on his own track, “Two Words,” from The College Dropout. No matter. I had my own secret weapon, Kendra Ross, my good friend whose father let us record some of Black Star at his studio. Kendra brought some of her singer friends to the studio to complete Kanye’s gospel vision. Abby Dobson, who I’ve worked with extensively throughout my career, is one of the voices on the hook, along with William Taylor and Vernetta Bobien. Chinua Hawk translated Kanye’s high-pitched wail into a run for the ages that my fans love trying to duplicate at the shows. The moment the song came together, I knew it was special.

“Get By” was massive out of the gate. The song was extremely well crafted. I was an underground favorite and Kanye West was becoming the face of hip-hop. DJ Enuff began to play “Get By” on his trendsetting mix show on New York’s Hot 97, which led to its being added into the rotation. Big Von from KMEL in the Bay Area jumped on it around the same time, and by getting “Get By” to spark off in the country’s two biggest hip-hop radio markets, we got the video played all over BET and MTV, which led to radio play on every hip-hop station in the nation. I asked Jay-Z to get on the remix, and he agreed, via two-way pager. After not hearing back from him for two months, I received a cryptic text from Jay that said, “What’s your email address?” Moments later, I had the recording session of a Jay-Z verse to “Get By” in my inbox. When I ran into him again later that year, I insisted on paying for that verse. Jay refused to take my money. He informed me that he charges entire recording budgets for a verse and that he was giving me that verse out of love for the culture.

Jay-Z was far from the only rapper willing to lay a verse on “Get By.” Busta Rhymes was also gracious enough to send me a remix verse thru email days after the song came out. When I sent my rough Jay-Z/Busta Rhymes “Get By” remix to Kanye for approval, he was in the studio with Yasiin, and they both added verses. Before I even heard their verses, Kanye was up at Hot 97 with DJ Enuff, playing “his” remix on air. Snoop Dogg added a verse to what became a West Coast version of the remix. And 50 Cent used the beat for one of the many mixtape songs he dropped in 2003. “Get By” was becoming a monster hit that I could not control. I needed to stop fighting it and let it be great.

By the spring of 2003 “Get By” was a bona fide hit, and MCA Records had been absorbed by Universal Music Group’s Geffen Records. Aided by the hottest names in hip-hop, the “Get By” remix seemed like an unstoppable force of nature. That was, until it landed on the desk of Def Jam executive Lyor Cohen, who contacted Rawkus to find out why Def Jam’s most profitable artist was giving credence to this underground movement by doing songs with the likes of me. While Jay-Z had graciously agreed to record a verse for me out of respect for the craft, Roc-A-Fella Records’ contract with Def Jam at the time stipulated that Def Jam had to give permission for all Jay-Z feature appearances. Lyor Cohen did not approve of Rawkus or Geffen making any money off Jay-Z. A cease-and-desist letter was sent to all radio hip-hop DJs and radio stations, which scared them out of playing the remix; it went from almost two thousand weekly spins to zero in a week’s time.

My success has never been defined by what was playing on the radio, and I was blessed that “Get By” also helped with the shows. After it dropped, my show became one of the hottest commodities on the hip-hop touring circuit, along with acts like the Roots, De La Soul, and Common. While I was opening for Common as he toured his Electric Circus album around the country in 2003, Kanye asked if he could come on tour with me. Kanye was already becoming one of my favorite artists. He was struggling to get a record deal, and I was struggling to understand why. To my ears, the bars he went around spitting to anyone who would listen were pretty impressive. The rest of the industry seemed to be so blinded by his superb production that they couldn’t even hear his rhymes; they were too busy trying to get his beats from him to care.

I heard most of Kanye’s 2003’s College Dropout on Common’s Electric Circus tour during the spring of 2003. I also heard the rhymes for “Gold Digger” and “Hey Mama,” songs that didn’t get revealed until Kanye’s Late Registration album from 2005. Herein lies the genius of Kanye West. Everything the man says is going to happen, does. He is the concept of manifest destiny reworked as a Black boy from the South Side of Chicago. He is the living, breathing definition of speaking truth to power. When he first played “Hey Mama,” now my favorite Kanye song, for me, I implored him to drop it immediately. His response? “Nah, that’s going on my next album, Late Registration.” Here he was without a deal for his first album, and he was saving heat for the second one, and it was already named. When I first heard him say in “Jesus Walks” “here go my single, dawg, radio needs this,” a full six months before he had a deal, I thought he was being audacious at best. I also did not think that a hip-hop single about Jesus would get any play. I was wrong on both accounts.

When Kanye hopped on my tour bus in 2003, he was already saying he was going to be the biggest hip-hop artist in the world. He told everyone that his first three albums would be The College Dropout, Late Registration, and Graduation. Most folks nodded and smiled, while others outright questioned his sanity. Kanye was unbothered. He was like a firecracker, always energetic and always ready to rhyme. I would bring him out halfway thru my set to do his verses from “The Bounce” and an early version of “Two Words,” then we would go back and forth rhyming for a few minutes. At times Kanye would walk up to the DJ, stop the music, and spit a cappella a new rhyme he was working on. He would interrupt my set and change its direction. I was the first person Kanye said “I’ma let you finish, but . . .” to.

People sometimes say to me that I put Kanye on. I didn’t put Kanye on—he put himself on. When I brought him on tour with me, it wasn’t a favor. I did it because he was talented and he made my show hotter. I had homeboys who rhymed that I didn’t bring on tour with me because I didn’t feel they were as passionate about it as I was. I think Kanye may have been even more passionate than I was, which is saying a lot. He may be the most passionate person I ever met. Kanye West is so passionate about what he does that those who lack passion in their lives feel threatened by him. When he went on CNN and said that George Bush didn’t care about Black people during the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, he vocalized what many of us felt at the time, and he meant it. No other Black celebrity as big as Kanye was then would’ve dared say something like that in public. Kanye West has proven thru his lyrics and public statements that he has a deep, deep love for the Black community he was raised in.

The more control Kanye West got over his output, the more “conscious” his output became. As an MC heavily influenced by Common, dead prez, Yasiin, and me, and the son of a college professor, Donda West, Kanye applied his lessons heavily on many songs throughout his career, such as “All Falls Down,” “Lost in the World,” “Murder to Excellence,” and many more. On Yeezus, an album that Kanye unconventionally marketed by projecting his face on sixty-six buildings across the world, he upped the conscious ante by rhyming intelligently about the causes of our pathologies rather than the symptoms. By comparing himself to King Kong on “Black Skinhead” he simultaneously critiqued those who feel threatened by his success as a Black man and made a nuanced commentary on the public’s perception of his marriage to Armenian-American reality TV star Kim Kardashian. On “New Slaves” he talks about the prison industrial complex with an informed flow that people would expect to hear from an underground activist MC like Immortal Technique before they heard it from the world’s biggest pop star. By declaring himself a god on “I Am a God,” Kanye brings the influence that the Five Percenters have had on hip-hop full circle. Kanye became the MC that the hip-hop purists say they wanted, the MC able to balance the debauchery with the content while keeping the music fresh. However, once you belong to the world at large, the hip-hop purists begin to feel betrayed.

Kanye ended up getting his deal with Roc-A-Fella/Def Jam Records, but not until he put out the song “Through the Wire” and paid for the accompanying video himself did they take notice and begin to support him. “Through the Wire,” which was built around a sample of Chaka Khan’s classic “Through the Fire,” featured Kanye West literally spitting thru the wire, struggling to get the rhymes out while his jaw was wired shut as a result of a 2002 car accident. It is one of the most impressive hip-hop performances ever captured on tape. The song became his first hit, and he did it without the help of any record label. His story sold the song, and its success helped create the buzz he needed to drop his debut album, The College Dropout.

By 2004 Kanye was so in demand as a producer that spending time with him was a feat in itself. The days of getting CDs full of Kanye West beats were over, as he preferred to create on the spot, not just because all his beats would immediately sell but also because it helped him to create more organically. When he visited one of my sessions for my Beautiful Struggle album, rather than give me a beat that was already done, he created the beat and the hook for what was to become “Get Em High” as I watched. Not only was that skeleton of a beat not the vibe I was looking for, I didn’t want to do a song about smoking weed. Kanye passionately tried to sell me on the beat, to no avail. Instead, I chose a beat that was fully realized and had John Legend singing the words I try over and over on it. I replaced John with Mary J. Blige and “I Try” was born.

Three months after that Beautiful Struggle session I was on tour in Europe while Kanye was in New York putting the finishing touches on The College Dropout. On a December day I received a frantic call from him; he needed a verse from me on his debut album, but I had only one day to turn it in or else it wouldn’t make the album. I was in Copenhagen, Denmark, so I booked a studio after my show that night and opened up the email that contained the song he wanted me on. It was “Get Em High.” By putting this song on his debut album Kanye found a way to get me to rap to the beat he originally made for me.

Not only did Kanye succeed at getting me on that beat, but by not making the song about weed even though weed references were in the chorus, he expanded my understanding of what the song could be. Everything he rapped about on “Get Em High” was real. He was hanging out on BlackPlanet.com back then, and people thought he and Damon Dash were assholes. By rhyming about how he used my name for “picking up dimes,” he teed me up nice and helped me find subject matter for my verse. After sending Kanye the verse thru email, I didn’t hear the song again until it came out. The day The College Dropout dropped, I was so excited about it I had my tour bus stop at a Target first thing that morning to purchase my copy. As I listened to the final version of “Get Em High” for the first time, a feeling of dread welled up in me and a look of horror crossed my face. My verse was placed in the song a bar later than where I laid it, which threw the flow I was going for completely off.

When working on music thru email rather than in person, it becomes easy to get creative signals crossed. Hip-hop beats are four-bar loops, so instead of my verse starting on the first bar, it came in where the second bar would be. To this day, it doesn’t sound quite right to me. I don’t know if it was the fault of the engineer on my end or the engineer on Kanye’s end, or if it was just where Kanye decided to place the verse upon hearing it, but I had to quickly go from the horror of realizing that the verse would sound off to me forever to begrudging acceptance of it. The album was already out; there was no going back. When I got Kanye on the phone that day to find out where the breakdown in communication happened, he didn’t know either, but he did say he loved the way it sounded. As I braced myself for critics to start saying I sounded off, the opposite occurred. People loved the verse and the song, and my place on one of the greatest debut albums in hip-hop history was cemented. To this day I perform my verse on that song all over the world, and people go crazy when they hear it. Either Kanye heard something I didn’t hear or I had to chalk it up as a beautiful mistake.

On The College Dropout, Kanye introduced the world to his contradictions, and he’s utilized them for the content of his songs for the rest of his career. For every “The New Workout Plan” there was a “Spaceship,” for every “Good Life” there was a “Diamonds from Sierra Leone,” and they are all excellent pieces of music. Kanye displayed an affinity for Black history, pornography, the working class, and the 1 percent, sometimes all in the same verse. As one of the first hip-hop superstars to be equally influenced by the artists on Rawkus and Roc-A-Fella, he straddled the line and brought those two worlds closer together.

Everybody has contradictions—why should artists be different? Because the artist’s platform can be so much bigger than the average person’s, artists are often held to a higher standard in the eyes of their peers. The responsibility of this expectation falls on the artist, not the consumer of art, but too often the consumer fails to realize that the artist can be a victim of the same pathologies as those that he/she is making the art for. I challenge this expectation because I think that contradictions in artists should be celebrated. I don’t want my art holier-than-thou, I want it eye level. I can remember KRS-One being called contradictory by hip-hop journalists all the time because he often switched his philosophical outlook and did so publicly. These contradictions make KRS-One a more genuine artist to me, and it is KRS-One’s name that will remain thru history, not his critics’.

My theory about contradictions and my support of Kanye were put to the test when I saw him support Donald Trump, first onstage at a concert, then later standing next to him in front of Trump Tower with a fresh blond do. As much as I wanted to embrace this obvious contradiction, I could not. Everyone has a line in the sand, and fascism is mine. From the time Donald Trump kicked the journalist Jorge Ramos from a press conference while on the campaign trail to his attempt to ban Muslims and his “many sides” defense of Nazis marching in Charlottesville, Donald Trump has never proven himself to be anything but a fascist. In my eyes, no normalization of this behavior should be tolerated. Even if we put aside the time Trump called Black people lazy, the time he called Mexicans rapists, the time he called Elizabeth Warren Pocahontas, the time he was caught on tape admitting to sexual assault, and all the terrible things he said and did before his presidential campaign, we are still left with a reality TV star who once body-shamed Kanye’s wife, Kim Kardashian, by talking about her body in a disparaging way on The Howard Stern Show.

Kanye West was not the only Black entertainer who disappointed me by standing next to Donald Trump. The Hall of Fame football player Jim Brown, the comedian Steve Harvey, and the singer Crisette Michele, all highly respected by the Black community and by me, all made the trip to the Trump White House to offer an olive branch to the Donald. If you were a celebrity with a modicum of success before 2017, you were probably in a room with Trump at some point. Celebrities are often sheltered and can relate to other celebrities more quickly than they can relate to the average citizen. Given their hyperbusy schedules and disconnect from what average working-class or poor people go thru daily, celebrities can often miss things that others don’t have the luxury of avoiding. For this reason I engage a lot on social media and show up in the flesh at community-organized events that push for justice and equality. Without knowing the fast-moving, ever-changing language of the activists who do the work whether or not the camera is on them, it is easy to have lofty, high-minded goals that may take earned celebrity privilege for granted. My belief is that the Black celebrities who were cherished by the community and wanted to give Trump a chance were operating with the best of intentions. However, when it comes to oppression, intent does not matter, only results do. That the road to hell is paved with good intentions is not just a saying. I don’t believe these celebrities were operating from an informed place.

A year and a half into Trump’s presidency, it became clear to me that anyone still supporting Trump was being willfully ignorant. I’d assumed that Kanye had changed his mind about Trump when he deleted his pro-Trump tweets, but that assumption was proven false when Kanye, responding to my criticism of his support for the conservative YouTube personality Candace Owens, told me that he loved Donald Trump. Earlier in the year, Candace Owens, a Black woman, trolled me on Twitter, suggesting I was not equipped to debate her on a YouTube channel called The Rubin Report, a place where white supremacists go to pat one another on the back. When Candace Owens came after me, I was called nigger, monkey, and various other racial slurs for weeks by her cultlike followers. Kanye, to my disappointment, did not seem to mind my being treated this way by the followers of a woman he chose to uplift.

Later that week, Kanye repeated his love for Trump to Ebro Darden, a personality on New York’s Hot 97 radio station. When Ebro made Kanye’s feelings public, Kanye spent a couple of weeks doubling down on his love for Trump with shortsighted tweets and bizarre interviews. Using right-wing catchphrases such as diversity of thought and pushing white-supremacist talking points about Black-on-Black crime and slavery’s being a choice, Kanye pushed himself further and further away from the community that embraced him while he was coming up and found a home with the same right-wing white supremacists that damn near called for his death when back in 2005 he said that George Bush didn’t care about Black people.

As a friend of Kanye’s I found myself in the unique position of being able to relay to him directly how the community felt, but I’m not sure he heard me. It’s hard to tell a self-made man who has accomplished as much as Kanye has that he is doing “him” wrong, but freedom has never been free. Kanye’s push for his personal freedom comes at the expense of Black people, and he is now being weaponized against us by people who will turn against him when he stops parroting their talking points. I think Kanye is smart enough to wake up and realize this one day, so I will be praying for the day he comes back home. As Dave Chappelle has said onstage, Kanye is still ours. Even the ugly parts we do not like.

While I cannot support Kanye while he supports Trump and various other white supremacists, I never stopped respecting Kanye as a man, and I don’t think I ever will. That being said, as long as he supports Trump, I will not be able to support his music. This saddens me because the music that Kanye has made has helped to make our lives brighter, and he has previously used his music to shine a light on the tragedies that poor and oppressed communities go thru. He is the antihero who became a hero despite himself. So the question is, who are you? Are you the hero, or the guy in the crowd making fun of the hero’s shirt?

Originally Appeared on GQ