Would Susan Sontag Love the Met Gala’s Homage to Camp? Her Biographer Investigates

Susan Sontag would have loved the Met Gala. (I'll get to the hate in a moment.)

This year it's inspired (at least in part) by her. Since its beginnings as a fundraiser for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, the gala has become perhaps the most paparazzied evening in the fashion calendar, with each year’s celebration putting the spotlight on a different theme. This year, it pays homage to Sontag’s essay “Notes on ‘Camp.’”

Published in 1964 in the Partisan Review, a legendary literary and political quarterly, the essay made Sontag famous. It was daring, naughty. “Many things in the world have not been named,” she wrote, “and many things, even if they have been named, have never been described.”

She, and then her legions of imitators, were determined to name these unnamed things and filled libraries with writing on subjects that serious people hadn’t written about-or hadn’t written about seriously, before.

One such subject was a particular flavor of homosexual taste called camp. An early draft of Sontag's essay was called “Notes on Homosexuality,” and the piece, later published as part of her collection Against Interpretation, can be read as a codification of gay taste. "The essence of Camp is its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration," wrote Sontag. "And Camp is esoteric-something of a private code, a badge of identity even, among small urban cliques."

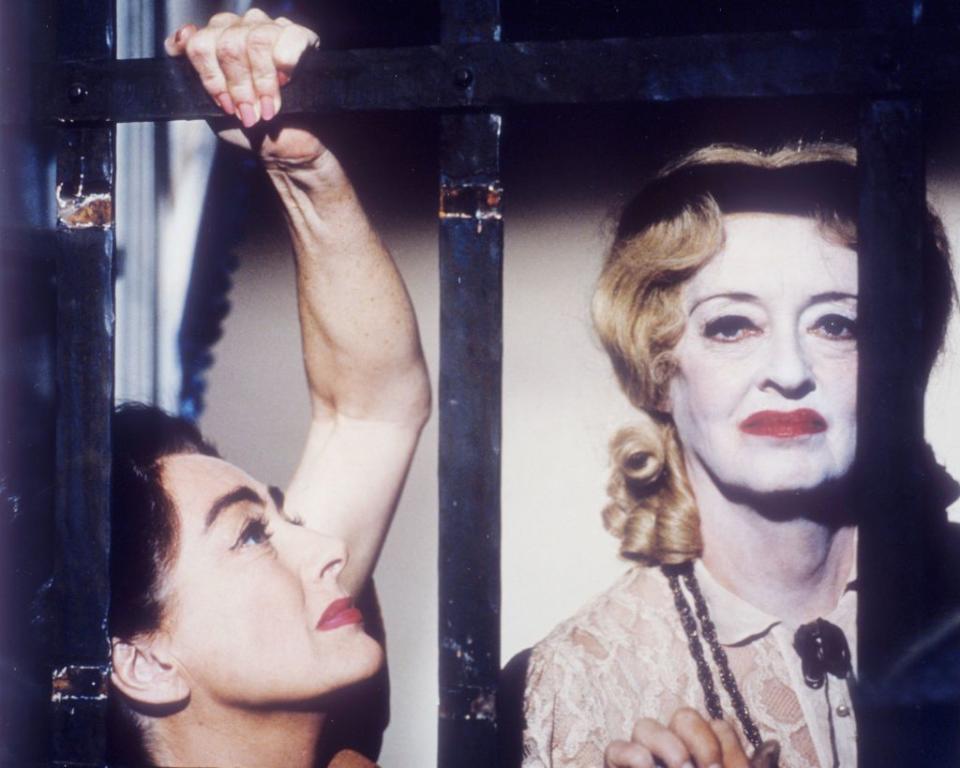

Sontag patiently explains why Cocteau is camp but not Gide; Strauss but not Wagner. Caravaggio and “much of Mozart” are grouped, in her ranking, with Jayne Mansfield and Bette Davis; John Ruskin effortlessly sidles up alongside Mae West. The true “aristocrats of taste,” she wrote, were homosexuals, whose “aestheticism and irony,” alongside “Jewish moral seriousness,” made up the modern sensibility.

Thanks to Sontag, camp came to symbolize the new, liberal attitude toward sexuality, politics, and society that we associate with the 1960s. Today, when we read “Notes on ‘Camp,’” it seems fun, funny-and not a little dated. But when it was published, many people responded with outrage. As the birth-control pill threatened male supremacy and the black civil rights movement threatened white supremacy, “Notes on ‘Camp’” was a threat to heterosexual supremacy. “Notes on ‘Camp’” was part of a broader movement to overthrow established hierarchies.

Camp was resistance.

Homosexual taste had always been an undercurrent in art, but it had rarely been named as such: to do so would have been to shove it into a ghetto, whose denizens were widely assumed, at the time, to be sick, deranged, and perverted. Sontag would have loved seeing this outsider’s sensibility embraced in a temple of the establishment like the Metropolitan Museum.

Susan Sontag would also have hated the Met Gala.

“I am strongly drawn to Camp,” she wrote in her essay, “and almost as strongly offended by it.” She was well aware that one risk of opening up critical hierarchies too much was that they would be replaced by an even more powerful hierarchy: the one whose measure is dollars and cents.

Sontag was a lifelong champion of difficult art, the kind of art that rewarded years of patient study, the kind of art that was constantly threatened by a society that prized glitz and gloss. She was deeply uncomfortable with the idea of celebrity-the reduction of a person to the image of a person-and would have been nervous about an event that celebrates tabloid fame so unironically.

In a world where gay people are murdered every day, she would have been alarmed to see a profound critique of mainstream society appropriated for an event that symbolizes the insider realm from which gay people have been excluded. And in a country where people beg for insulin on Craigslist, she, a lifelong activist for social justice, would have been disgusted an event with a $30,000 per person ticket, and by the obscene sums attendees spend on clothes and jewelry.

In gay aesthetics, she saw “a criticism of society,” a “protest against bourgeois expectations.” And so Sontag would have been thrilled by any partygoers who-at this most bourgeois event, in this most establishment of venues-stayed true to the fighting, mocking, winking, outsiders’ spirit of camp.

Benjamin Moser is the author of the forthcoming Sontag: Her Life and Work, out September 17 from Ecco.

('You Might Also Like',)