The Subtle Art of Being Richard Marx

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“Hearst Magazines and Verizon Media may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below.”

Richard Marx didn’t know what hit him. It was 2019, and he was sick—sickest he’d ever been in his life—with something that came on fast and intense. Fever. Chills. Aches. “I’m almost cocky about how I never get sick,” Marx tells me from a hotel room in Miami, “but I really was thinking I was going to die.” A diagnosis eluded his doctor, so he visited some of the nation’s top infectious disease experts. They were stumped, too. But one thing Marx knew was that this mysterious illness would not stop his 2019 solo acoustic tour.

“At showtime, it was like Weekend at Bernie’s,” he says. “They’d be propping me up, but then I hit the stage and something took over.” He laughs, a little at the situation and a little at himself. “My wife, my manager, everyone was like: dude, go home and rest, and I said, ‘My voice sounds good and my hair looks great, we’re doing this.’”

That’s Richard Marx all over: headstrong and confident, in possession of a gift so undeniable, not even illness would try to stand in its way. Marx arrived in the summer of 1987 with his self-titled debut album and was a constant on the pop charts for most of the next decade. His were the pop-rock songs we were listening to in the time when we were all listening to the same pop-rock songs, and often those songs provided the soundtrack to the same experiences. The Song of the Summer can come from anywhere, but for three years running, with “Endless Summer Nights,” “Hold On To The Nights,” and “Right Here Waiting,” Marx mastered The Song of the End of the Summer—the one that’s playing when you walk away from a summer romance, or tearfully head off to college. That’s the work of a pro. And the late ‘80s, early ‘90s pop-rock of which Marx is an icon is experiencing a renaissance this summer thanks to a more recent pop-rock standard bearer, John Mayer. His new album, Sob Rock, borrows many of the riffs, vibes, and graphic design of Marx’s early years. It’s no coincidence one of Mayer’s musical collaborators on the record is Greg Phillinganes, who worked with Marx in the ‘80s and has been a close friend ever since.

Marx continues to record music, but now he’s as ubiquitous on Twitter as he once was on the charts. He’s transformed himself into a sane and sensible flamethrower; his politically charged tweets are smart and savage, and he’s secure enough with his place in the rock music canon that his tank of fucks is sitting on empty. Who better to take Rand Paul down a notch? “Oh yeah, Rand Paul is a horrible, horrible, horrible reprehensible degenerate piece of shit,” he says, “and you can quote me on that.”

Nearly 35 years after his arrival, Marx—his music, his opinions, his story—is having a moment. Stories To Tell, his memoir, came out July 6, and it manages to be dishy and discreet, foul-mouthed and family-friendly. “I feel like when you’ve been around for a long time, provided you don’t display yourself as a prick, you get people to root for you,” he says. Try not to root for Richard Marx; he’s an American treasure, an unparalleled Twitter troublemaker, and now, though nobody seems to know precisely what he’s a survivor of, he’s a survivor.

Marx, 57, is healthy as a horse as we speak, and he doesn’t know what that’s all about either. “I maintain a certain level of either vodka or tequila to keep it at bay,” he says, and that’s that on that. Looking back has never been a habit of his, which can make the process of writing a memoir somewhat more challenging. “Up until a year ago, I kept saying I don’t want to write about my personal life, I want to write about the lives of the songs.” So he did, and he sent some pages in. “My editor called up and said, ‘I like this, you have a unique voice and your humor is coming through, but I feel like your hesitation to write more about your life and your journey as a man is steeped in fear.’” Some editors know exactly how to motivate a writer. “I said, ‘Okay, well, fuck you, now I have to write that.’"

He says that from there, conquering the blank page as a memoirist was much easier than doing the same as a songwriter, and then he admits almost immediately: “The blank page in terms of songs actually doesn’t trouble me that much either.”

Marx is among the best to have done the inescapable, summer-defining song, and he may have been among the last; things don’t stick in the cultural memory like they used to. “It’s all so transient,” he says. “These songs that become massive for a minute don’t seem to have legs for the most part.” We’re the problem, according to Marx. “Don’t you think that’s just consistent with the culture? There’s nobody who doesn’t have ADD now. When I’m listening to somebody’s record, I’m an asshole like everyone else—I’m answering a text, I’m wondering who plays guitar on it and then I’m looking it up. I can’t remember the last time I did one thing without doing something else.”

“When I think about it, it depresses me momentarily,” he says, and then, everybody now: “but then I go: it is what it is.”

According to him, and his is a word I would take on this, popular music is as good as it’s ever been. Having collaborated with just about all of his heroes—Stories To Tell includes chapters on Lionel Richie, Kenny Rogers and Barbra Streisand, to name a few—his dream co-writers are now his descendants. "My list now is all young people,” artists like Tove Lo, “and they don’t need my help, I need theirs.” At an age when people disengage, Marx refuses to stop learning about pop music. "One of my pet peeves is when I’m around some of my peers, and they fall into this rhetoric of there’s no good songs anymore. Fuck you, you’re not listening.”

He writes songs with his middle son Lucas, who’s very steeped in mainstream pop, “I don’t have an instinct to club everybody over the head and say ‘do you know how many hits I’ve had, we’re doing it this way.’ My instinct is to go, ‘what would you sing here?’ I want to learn.”

He’s a more Zen, less anxious guy than he’s ever been, something he chalks up to hiking, therapy, and I swear to God, Twitter. Marx is a consistently hilarious follow on that hell-site, serving his followers a mixture of self-deprecating humor and merciless takedowns of our nation’s hapless new crop of villains. “There are certain triggers for me, and racism and bigotry are at the top of the list. When I see something racist or bigoted or ignorant, I’ll pull out my phone and tweet that shit, and then I’m not angry three minutes later. I don’t carry that shit around with me.”

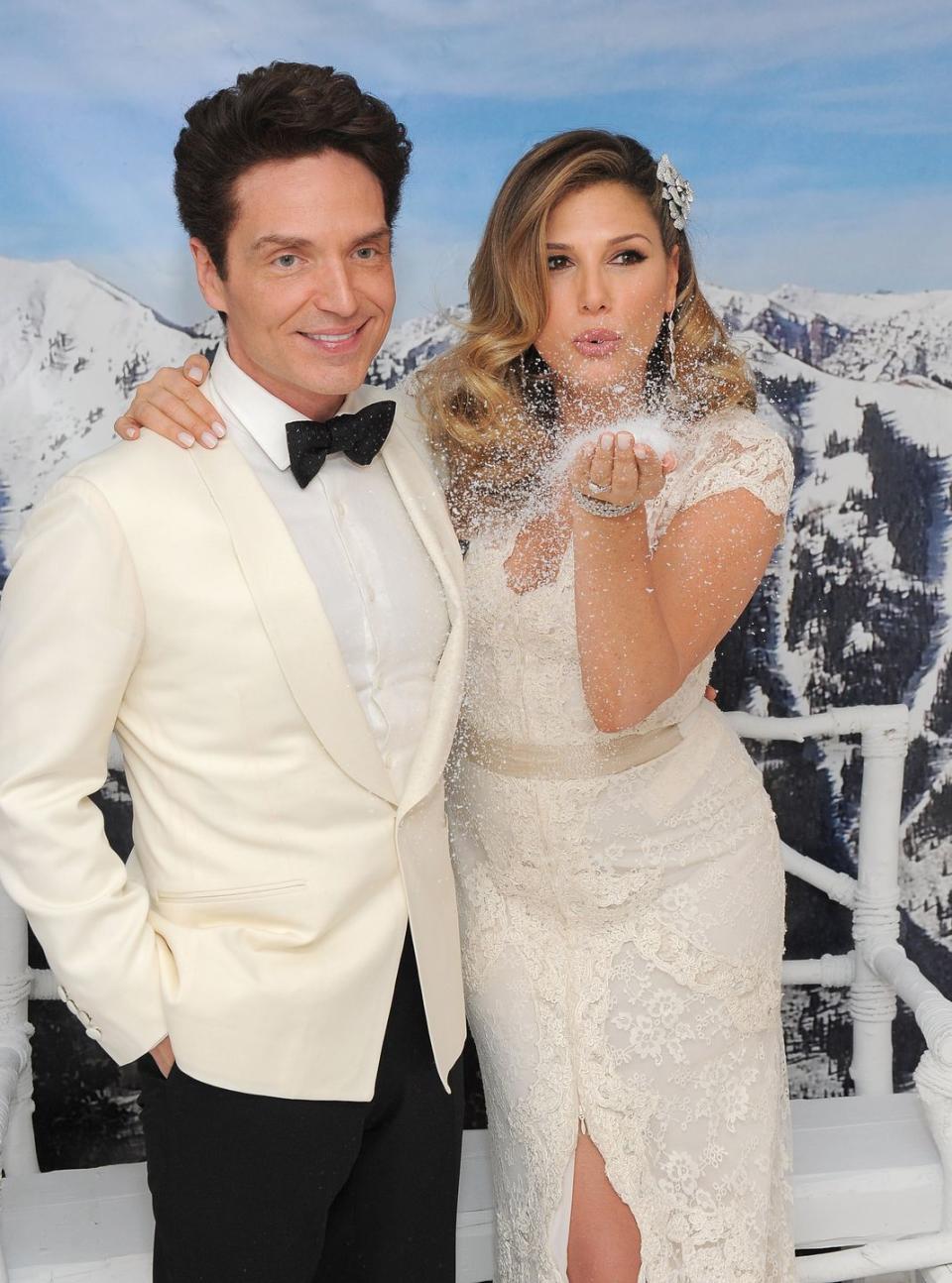

Stories To Tell may have been easier to write than a song, but it’s been harder to let go of, more emotional to put out into the world. “I’ve put my heart and soul into it, and I want it to be well-received. It’s the same with my music, but I always know I’ll do another record. Putting this out, I thought: this is it, I’m not going to write multiple memoirs.” His wife, former MTV VJ Daisy Fuentes, challenged him on that. “She said: ‘won’t you have more stories to tell?’ I was like: holy shit, you’re right. I can just write about shit whenever I want to. That’s taken some pressure off.”

As fascinating as it is to read the thoughts and stories of a master songwriter whose songs have soundtracked your own thoughts and stories, the most refreshing thing about the book is that confidence of his. He’s absolutely certain of his talents, and of his significance in the culture, but never in a way that tips over into egomania. It’s inspiring in its own way, this simple self-assurance. “I don’t think you can truly be successful without a sense of that,” he says, “but you don’t have to abandon your sense of humility and gratitude. They can all live together. If my sense of gratitude for my existence comes through in this book, that’s what I want people to come away with.”

He says he’s been asked a million times what his favorite of his own songs is, but while you have him on the phone, you almost have to. “Don’t have one,” he says for what is clearly the millionth-and-first time. But then he remembers something from that 2019 acoustic tour that he nearly died on. “I said to the audience, ‘I’ve been asked a million times if I have a favorite song I’ve written, and I don’t. But the song I’m about to play I now can say is the most important song I’ve ever written, and it’s “Don’t Mean Nothing.’” And the reason it’s so important is because it’s the one that introduced me to the people who know what I do.” It was his first single, and as we learn in Stories To Tell, its lyrics are ripped from his own experience navigating the music business as a young songwriter. “I was 22 and just full of cynicism. I look at the lyrics, and I go: bro, I want to hug you.”

He can’t, of course, but he can offer that kid a different kind of support, from where he sits 35 years later: “Also, I’m sorry, but it’s just a great fuckin’ song.”

You Might Also Like