The Strange, True Tale of the 'Yankees Suck' T-Shirt

There are certain two word phrases that seem destined for each other. Where their coupling achieves a sort of simple, evocative poetry. Summer's breeze; good dog; sand castle; cold beer, and perhaps most effectively, in New England vernacular anyway: Yankees suck.

The proclamation is well trod by now, but there was a time around the turn of the millennium when it was just reaching its zenith. It had become a sort of mantra for the people of New England—at Fenway Park, of course—but also anywhere else people gathered: weddings, birthday parties, games where neither the Red Sox or the Yankees were even involved. It could even serve as a greeting between two people passing on the street. "Yankees suck?" "Yankees suck!" Never mind that it was the furthest thing from the truth. In the midst of a particularly impressive run of World Series victories, the Yankees, objectively, did not suck at the time. And yet, to Bostonians, they did. They really, really did.

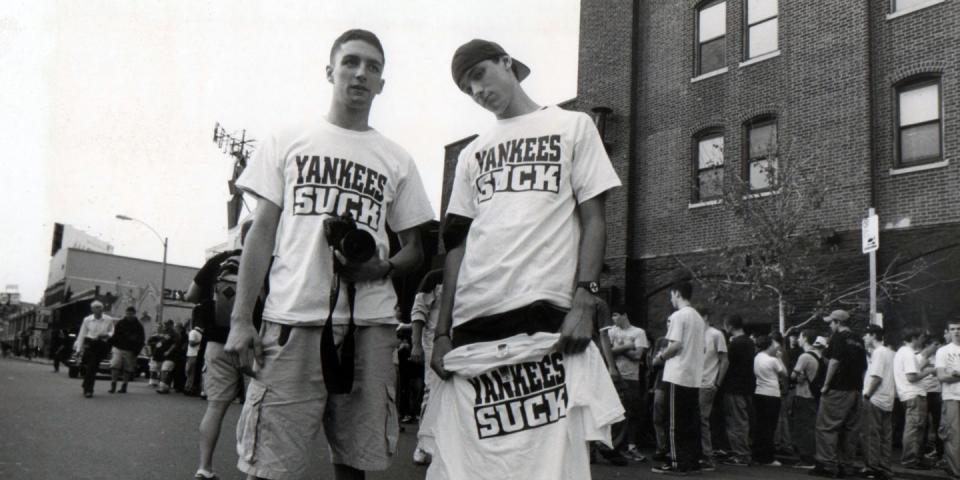

That's where Ray LeMoine and friends come in. Around 1999, the Northeastern University student and Fenway Park vendor enlisted a group of friends from the Boston hardcore scene to capitalize on the wave of anti-New York sentiment by printing up T-shirts featuring the phrase. They were simple, straight to the point, and a sorely needed middle-finger to the evil empire that married the edgy attitude of the hardcore world with the identity-consuming sports fandom. The rise and fall of LeMoine and his crew were the subject of a riveting Grantland piece from 2015, which was optioned for a film by Pyewacket Pictures' Gillian Greene, wife of Sam Raimi. And now their exploits are the focus of an ESPN 30 for 30 podcast that premiered this week.

"Hating the Yankees is part of our heritage," ESPN's Julia Lowrie Henderson explains in the piece. "It has brought generations of Bostonians together. But Ray did something none of the rest of us did. He took that hatred and made a shit ton of money off of it."

A shit ton, kid.

In the few years they roamed the streets of Boston, selling hundreds of shirts a day, and pulling in an estimated hundreds of thousands of dollars, the crew essentially operated like a drug operation, including some of the attendant violence—"$10 crack rock for jocks," they called the shirts. But it came about at a time of change, both for the city of Boston and the world. They went from streetwise kids hustling T-shirts outside Fenway to high-rollers with more money than they knew what to do with. They were buying expensive suits and watches, traveling the world, and, eventually for some, trying to make the transition into drugs. One of the crew, Todd Wilson, eventually got shot trying to fend off a group of robbers in a drug deal gone bad.

Then came 9/11, new ownership for the Red Sox, the stunning come-from-behind win in the 2004 ALCS over the Yankees, and—even more destabilizing for the sense of inferiority that had fueled Boston sports fans—a role reversal. You can't play the underdog anymore once you've become the bully yourself.

I talked to LeMoine (who I briefly worked with at another publication) about the story of his rag tag team, the crossover between music and sports in Boston, and how things will never be the same.

On the culture of Yankees hate:

It was an inferiority complex between Boston and New York. Back in the '90s, baseball wasn't that big—sports weren't as big in general in New England. Then we got Pedro [Martinez]. In '99 Pedro really came out and that was the year I ended up working [at Fenway]. Pedro Martinez made the Red Sox relevant. Rule changes to put in the extra round of the playoffs made it so we could in theory could have an ALCS against the Yankees, and we did. It was luck. I was working inside there. We didn't know the law about T-shirts or anything. There was another crew before us; they must have sold 20,000 shirts in the ALCS. The level of hatred, it didn't peak in '99, but that was the first time I saw a sports rivalry take over a region. Those games were like A1 news, for New York's 20 million people to another like 40 to 50 million people from metro New York all the way up to Maine. It became real for us as sports fans to understand the '80s better. I was a little too young for the Mets and shit, and the '70s, when Bucky Dent hit that homer—but it really put a focus on the two teams.

We just got competitive at the right time. Those four years between '99 and '03, Boston really hated the Yankees. I've been around to a bunch of other places where they have sports rivalries, but my sister, my grandmother, my mother, they were involved in this rivalry. If you go to Argentina and see River and Boca, grandmas aren't tied into it. I don't know that there's a comparable sport around the world where just like everybody got into it. By '03 and '04 women seemed like half the attendance of Fenway. It transcended gender and age, everything.

On the height of the shirts' popularity:

We peaked around '01. We were selling a lot. I can't give an accurate number. Most nights we'd do a couple hundred, on a good night we'd do several hundred. There were days I had a team down at the Fleet Center during the day for Celtics, then Red Sox at night, then Bruins the next day. Those were the craziest days.

The profits were better than drugs. You're not making a $9 profit of a $10 bag of weed. I was never really a big drug dealer because the profits weren't that good. But by the end everyone was investing their money in drugs because you can't put cash into a bank. The way we ran T-shirts was like how we ran a hardcore show. I started doing shows in '93, so it was the same mindset: You got a bunch of people and everyone has a task. We were fair, we'd profit share with our employees. It was less of a business and more friends who stumbled on a way to make money. I was political so I was thinking of it more in terms of making sure everyone had enough money to go around. But the money got really good.

On clashing with other gangs, and the end of the shirt game:

The T-shirt thing got diffused because [notorious Boston hardcore gang] FSU bought a stake into the shirt game. The scalpers never picked up on how many shirts we were doing. If they ever picked up on that we would've been out right then and there. The scalpers are all from Dorchester and Southie. These guys, their brothers are the police, it's still a very Southie, Dorchester Irish gangster story. Irish kids whose cousins are cops and shit. Notice there's no black scalpers in Boston? You ever see that anywhere else? The racism was still so bad, or was, until we left.

We were simpatico with FSU, but they turned on us. Some people got beat down, but not for shirts. Everyone is cool now, but there was a couple years that were hot. Even they, I don't think they were paying attention to how much money was being made down there. They would've wanted it for themselves. But somehow we kept the monopoly through '02. Having that monopoly was huge. But it would've taken a pretty serious crew to break into a group of 30-40 people. Only FSU could've figured out was what going on down there. By the time they did, what could we do? We weren't going to fight them.

On the overlap between sports and music in Boston:

I don't think any other hardcore scene had that. It was more about the clothes for a lot of the early bands: SSD, DYS. I never met those guys, but in some of the books about the era they say it was more of a fashion statement than anything. Boston was the only scene I can think of that was that tied into sports.

Before '99 no one in the scene cared that much about sports. The baseball and sports thing, it just happened to be the hardcore kids who worked down there. Yeah, our style was there, like the Youth Crew style in the late '80s looked sporty too, but we weren't really into sports. People are going to lie and say they were, but we didn't watch baseball games. Bullshit. Maybe some of the thuggier guys were into sports, but I don't even think the FSU guys were into sports. British punk was so drawn from the gay scene in London. It was a reaction to that. Hardcore kids didn't want to look like punks, so they said, "What's the opposite of punk?" And that look works, too; they're both timeless styles. The streetwear thing has lasted. It's harder to be a punk with a mohawk at work.

This story has been updated.

You Might Also Like