When Will We Stop Searching 'Who is Marsha P. Johnson?'

On Google's June 30 landing page, there is a doodle by Rob Gilliam. The woman at the center of it has a bright smile and red lipstick and a headdress fixed up with pearls and flowers. Behind her, four banners fly through the sky—for gay, bisexual, genderqueer, and transgender pride. This image is, in an ideal world, the perfect Pride. And as Pride month rolls to a close, especially in 2020, it only makes sense that this is the person who is featured on Google's homepage. Her name is Marsha P. Johnson.

Having Johnson as Google's face of Pride on the final day of the month is incredible. It has led to an uptick in searches about her life, and to truly celebrate Pride, you have to know about the life of Marsha P. Johnson. In a lot of ways, it is the foundation of the celebratory month. That's also why the doodle leaves me uncomfortable. This doodle suggests that this woman with the lipstick and pearls got to live in this celebratory world.

Celebrating Marsha P. Johnson means recognizing that her reality was not the sanitized image we find most comfortable. It requires that when we click on that Google image, we read the words behind it and process that the difficult stories of Pride heroes often get reworked and tailored to make death and injustice more palatable. Marsha P. Johnson is more than a brick at a pleasant riot. She's representative of so many other faces that still go unnoticed every day.

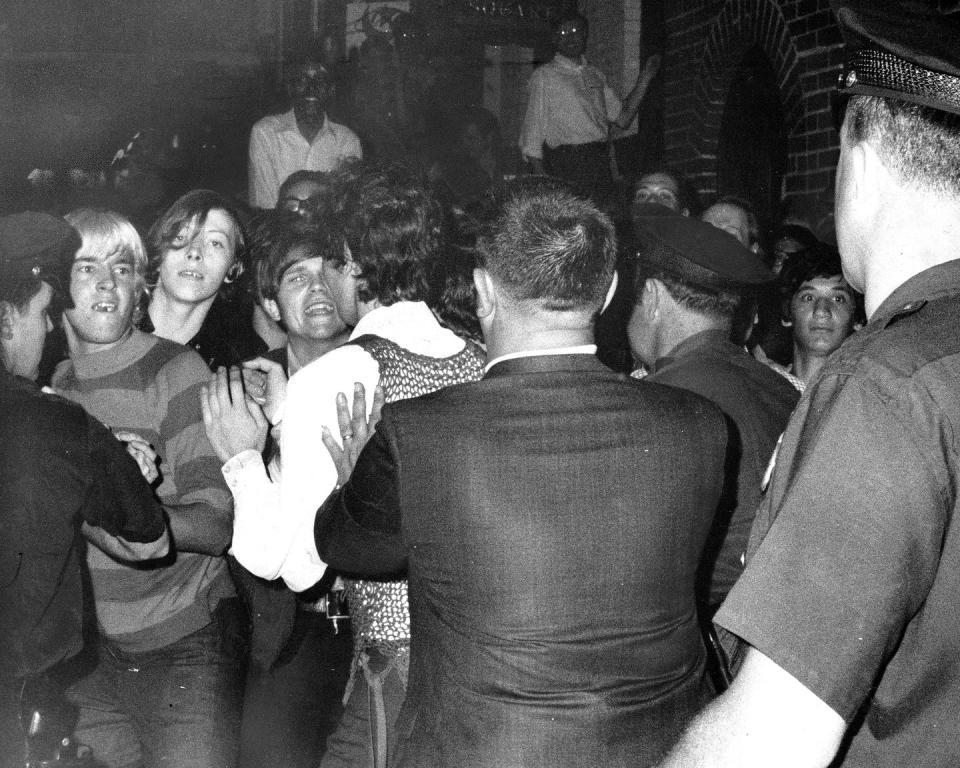

Johnson was a civil rights activist, and those with the most cursory knowledge of her place in history know her for "throwing the first brick at Stonewall." The Stonewall riots, which started on June 28, 1969, were a series of demonstrations at New York City's Stonewall Inn, a gay bar on Christopher Street. Drag queens, trans women of color, and other LGBTQ people fought against police who routinely raided LGBTQ establishments, demanding the police raids and inhumane treatment stop. On the night of June 28, lesbian Stormé DeLarverie fought back against her arrest, kicking off a standoff between law enforcement and the people hanging out at the Stonewall Inn.

That June 28 night was a breaking point for an issue that had been ongoing for years. There were countless instances leading up to Stonewall where trans people were arrested and jailed across the country for "public lewdness" or whichever other offense might be offer loose justification for arresting innocent individuals. There was no safe place to be—until the late '60s, even most gay bars were still exclusionary toward women, drag queens, and trans folk.

On that June night though, around 1 a.m , the fight for liberation escalated. Johnson later said that she wasn't actually there when the riots broke out, arriving later around 2 a.m. There was still plenty of fight to be had. The patrons of Stonewall pushed back over the course of two nights. In retellings of the riots, many remembered Johnson dropping a brick onto a cop car from a lamppost. Some say she threw a brick at an officer. Others say she threw a shot glass into the fires burning inside the bar.

The truth is, Johnson is worthy of much more than a debate about a shot glass or a brick thrown on a single night. She was an activist that lived boldly, refusing to exist within gender boundaries. She spent the better part of her life fighting for equality and the well-being of AIDS patients in the '90s. The popular story of Johnson's life is the one that takes place on a single night, but for years, she was a sex worker who lived on and off the streets, proudly standing for gay and trans rights before it was ever sponsored by any [insert bank here]. She was the definition of intersectionality—a Black, queer person who openly dealt with mental health problems. She represents so much of what we can be. Her death also encapsulates so many of the problems we face right now.

In 1992, Johnson's body was found floating in the Hudson River after a Pride parade. Police deemed it a suicide. Many of her friends disputed the claims, and multiple accounts describe other circumstances that suggest that Johnson did not take her own life. Documentaries have been made looking into the incident, and the police eventually reversed course years later, listing the cause of death as "undetermined" in 2002. All these years later, the death remains unsolved. Stories like Johnson's encapsulate a grisly truth about America and the suspicious deaths of Black people. A recent uptick in hangings have also been deemed suicides, though, like Johnson, family and friends suggest other unreviewed circumstances. And the cross-section of trans people and Black people murdered or violently killed in America is a damning portrait of which aspects of America we like to recognize. This year is already tracking for more trans murders than the last.

Those are the stories we don't look at because it's uncomfortable. To think of Marsha P. Johnson as we do in that doodle means that we don't have to recognize her reality. Stonewall can be a celebration where police were marching arm in arm with protesters. On the night of the Stonewall riots though, police were tearing people from a gay bar that had only recently decided that it would welcome trans people. Then it took 50 years for the New York City police department to apologize for it. And this year, just a couple days ago, as protesters took to the streets to advocate for Black queer liberation, police bulldozed through the crowd, knocking down demonstrators, using the same type of brute force that was utilized to intimidate and scare LGBTQ people a half-century ago.

When the #NYPD riots on the 51st Stonewall anniversary. #DefundTheNYPD #NoBillionNoBudget pic.twitter.com/a0XmiyW2vv

— Murad Awawdeh (@HeyItsMurad) June 29, 2020

Pride is much more digestible when the image is a cisgender white man wearing tight boy shorts on a float. Or a sketch of a happy Black woman that represents a shade of the truth. But Pride doesn't exist for a glitter bombed parade: it represents the suspicious deaths. The bloodied protesters. The Twitter videos from two days ago. The memory and progress of Marsha P. Johnson hinges on our ability to capitalize on the surge of support for the Black Lives Matter, paired with the fervor that comes with Pride. Those unjust realities are still the core of Pride because until it's representative and safe for everyone—until the rights of all LGBTQ people matter to the general public outside of June—Pride is simply a notion flying as haplessly in the sky as those four banners in Google's sketch.

Every couple years, we Google "who is Marsha P. Johnson?" and then we start to read the details and feel uncomfortable about it all: how she died and persevered and managed to advocate for people when so few people were advocating for her. And then we settle on the image that feels most comfortable. What if Marsha P. Johnson were a cis-passing Black, trans woman with light skin and nice clothes who threw one brick and then went home to her apartment in Chelsea? What if her flower crown was never messed up? What if, in this other world, there's an image of her deciding which color Sharpie to use on her protest sign? What if she's still living somewhere, perhaps on the upper East Side, telling children the story of when she was a one-night renegade?

That's not her story.

The least we can offer Marsha P. Johnson is to Google her legacy and learn it. Absorb it. Tell it to others. And one day, enough people will know it as a part of their American history that we won't have to Google Marsh P. Johnson again.

You Might Also Like